ARTÍCULO DE REVISIÓN

DOI 10.25176/RFMH.v19i3.2158

1 Cayetano Heredia Peruvian University, Lima-Peru.

2 Association Medical, Political and Health Agreement, Lima-Peru.

a Medical specialist in Health Management.

ABSTRACT

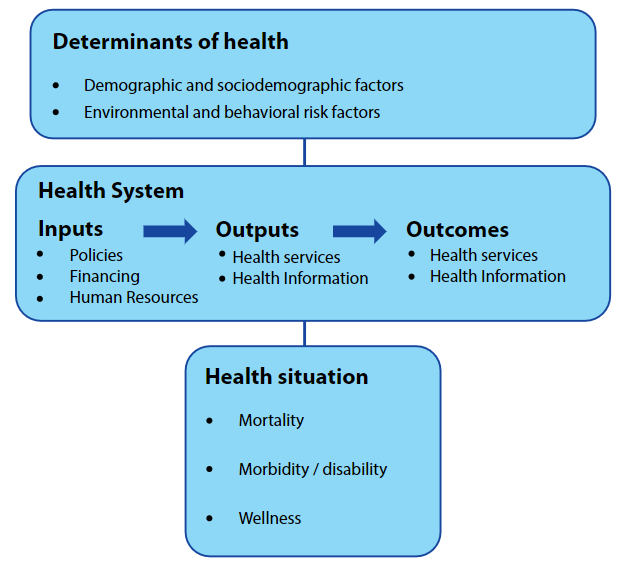

The policy of the Universal Health Insurance (AUS) established that access to health services will be carried out through the financial intermediation of health insurance, establishing for this four axes of "reform": plan of benefits, financing and payments, targeting of subsidies, service provision and regulation.

The policy of the AUS was based on the theory of quasi-markets where the intention of the State is to avoid being the provider of resources and the service provider at the same time; instead, it seeks to become the primary provider of funds to a variety of private, public and nonprofit providers, all operating in competition against each other.

Ten years after its implementation in our country, the progress made in the implementation of the reform axis proposed by the AUS policy is analyzed.

Keywords: Universal Health Insurance; Public Policies in Health; Health Care Reform. (source: MeSH NLM)

RESUMEN

La política del Aseguramiento Universal en Salud (AUS) estableció que el acceso a los servicios de salud se realizara por medio de la intermediación financiera de seguros de salud, estableciendo para ello cuatro ejes de “reforma”: plan de beneficios, financiamiento y pagos, focalización de subsidios, prestación de servicios y regulación.

La política del AUS se basó en la teoría de los cuasimercados donde la intención del Estado es evitar ser el proveedor de recursos y el proveedor de servicios al mismo tiempo; en lugar de ello, busca convertirse en el proveedor primario de fondos para una variedad de proveedores del sector privado, público y no lucrativos, todos operando en competencia unos contra otro.

A 10 años de su implementación en nuestro país se analizan los avances de implementación en los ejes de reforma que planteó la política del AUS.

Palabras clave:

Aseguramiento Universal en Salud; Políticas Públicas en Salud; Reforma de la atención de salud. (fuente: DeCS BIREME)

INTRODUCTION

The orientation of health policies in our country is not far from the spectrum of economic and social policies, in the latest trends, delineating the state model we have. Social trends have redesigned risks, weakened and restricted to specific groups. By default, gender asymmetries are perpetuated within families when it is a burden on welfare provision3.

Universal Health Insurance policy

In this context, based on the neo-business approach of the New Public Management, the Peruvian political parties of the early 21st century established the “Agreement of political parties in health” (2005) with the assistance of the United States Development Agency International (USAID)4, giving impetus to a set of health policies that shaped the “Universal Health Insurance Framework Law (AUS)” (2009).

The AUS policy established that access to health services will be carried out through the financial intermediation of health insurance, establishing four axes of “reform”: benefit plan, financing and payments, targeting of subsidies, provision of services and regulation5.

Next, an approximation will be made to the results of the implementation of the AUS policy through the analysis of its reform axes.

Benefits plan

The health benefits plan is the list of insurable conditions, interventions, benefits and explicit guarantees offered by health insurance to its members6. The minimum plan is called PEAS, it was approved in 2009 and covers procedures associated with 140 insurable conditions and 34 explicit guarantees of opportunity and quality77. Although the AUS Law established a biennial evaluation of the PEAS for its reformulation, ten years after its approval there is no public information on the evaluations carried out.

In effect, the AUS Implementation Plan established that by 2014 the PEAS should include at least 185 insurable conditions and 70 explicit guarantees, none of which is true as of date8.

Although the Comprehensive Health Insurance (SIS) extended the benefits package for its insured, there is no clarity about the capacity to provide the services, the population actually served or the costs of provision of the packages9. Finally, in the case of the private health insurance market, the lack of updating of the PEAS constitutes a limitation to the progressivity in the coverage of benefits for citizens who are listed in the benefit plans of the private insured who take as reference the PEAS.

Financing and payment mechanisms

Law No. 29761 (2011) established that the public budget for financing the subsidized SIS regime, take as a reference the value of the annual premium of the PEAS and the number of affiliates10. However, to date, the Law has not been regulated by the Ministry of Health and financing for SIS policyholders is predominantly carried out by the historical budget mechanism.

The lack of sincereness of the resources necessary for the financing of SIS policyholders largely explains the relegated position that our country still maintains in terms of public spending for health (3.3% of GDP for 2016)11, being that a necessary condition to reduce inequities and increase financial protection is to sustain a public expenditure for health not less than 6% of GDP12.

Similarly, in the last 10 years, out-of-pocket expenses (payment when receiving the service in the form of medications, co-payments or deductibles) have remained above 20% of the total health expenditure until 201611. Likewise, the catastrophic health expenditures (health expenditures that exceed 40% of the household's ability to pay) have not been significantly reduced in the 2006 - 2016 period, from 5% to 4% of affected households13.

On the other hand, the payment mechanisms for the purchase of health services, which should allow the providers to align incentives towards the achievement of health outcomes, have proved ineffective and have contributed to bureaucratizing the providers' administrative systems. The gap between the design and implementation of the mechanism for the purchase of health services through the “Results Budget” has not made it possible to overcome the payment for input to a true payment for results. In the case of the first level of attention, the systems called “capita” of the SIS differ from the basic system of the internationally captured mechanisms, recognized for privileging their calculations based on historical production; finally, in the case of payment to hospitals, the SIS makes the purchase based on the billing of services through rates that vary from hospital to hospital; also, recognizes the additional costs that hospitals may have incurred; However, administrative delays, resulting from transfers and administrative management, are frequent within providers that do not allow resources to be effectively available from the first month of each year9.

Focalization and subsidies

The efforts to identify the population in poverty condition used mechanisms of geographic targeting, individual targeting, targeting by criteria of vulnerable population; however, this contrasts with the fact that at least one third of the population in poverty remains in such a situation (chronic poverty) and the other two thirds record exits and entrances in relation to the poverty line14. The focus effort contrasts with the less attention that the important subcoverage of the SIS has received, according to Petrera, based on 2014 data, there is a subcoverage of the SIS of 68.6% for the first quintile and 60.4% for the second quintile of greater poverty in the area of Metropolitan Lima15.

Service provision

The expansion of the supply of health facilities in the pilot departments of the Universal Health Insurance policy in Ayacucho, Apurímac, Huancavelica and Metropolitan Lima during the period 2009-2018, in the MINSA / regional governments (GR) subsystem was 15 (4%), 112 (40%), 91 (28%) and 33 (9%) health facilities, respectively. In the subsystem of ESSALUD it was 1 (9%), 3 (60%), 0 (0%) and 17 (63%) health facilities in each department.

In the private sector subsystem, the expansion of the offer was greater with 24 (800%), 81 (506%), 22 (76%) and 5393 (376%) health facilities, respectively (Table 1).

However, the population of the SIS that failed to access health services, despite needing them, increased from 37.3% to 49.4% in urban settings and from 36.6% to 49.9% in rural areas during the period 2004-201415; that is, the expansion of the MINSA / GR health establishment offer has been insufficient to the demand for services by members of the SIS. Finally, the efforts destined to “benefit exchange” (attention of SIS affiliates in ESSALUD) have been ineffective, reaching only 1.3% of the total attention of SIS9.

Regulation and Control

The regulatory capacity of the Health Ministry in matters of insurance has been transferred to the National Superintendence of Health (SUSALUD), which exercises the function of inspection of the AUS16. By April 2019, according to the SUSALUD sanctions registry, a total of 74 sanctions have been filed since the entry into force of the Infringement and Sanctions Regulations in 2014. In the case of the Health Insurance Funds Management Institutions (IAFAS) are 12 penalties for a total amount of 142 UIT and in the case of the Institutions providing Health Services (IPRESS) there are 62 penalties for a total amount 1558 UIT17.

Final thoughts

The AUS policy prioritized in its design the financial dimension of the health system, focusing on aspects of allocative efficiency and equity in terms of financial protection, for this it was based on the quasi-market theory where the intention of the State is to avoid being the provider of resources and services at the same time; Instead, it seeks to become the primary provider of funds for a variety of private, public and nonprofit providers, all operating in competition against each other18. Even when the outsourcing of services is necessary, it is pertinent to explain that it is not the same to outsource from public convictions as from private convictions3. In the Peruvian case, during the implementation of the AUS policy, an outsourcing of services can be appreciated in a way reactive, poorly planned and with poor control mechanisms (private pharmacies "FARMASIS", emergency care in private clinics, the "negotiation" of the Moreno case). In sum, it was outsourced not seeking more efficiency and effectiveness, but rather outsourced to avoid hiring more staff directly.

Finally, it is necessary to mitigate the potential problems of a policy with deficiencies in public values such as the AUS; on the one hand, the possibility of intensifying the problems of “captures” of the regulator by the regulated, expressed in that senior public officials who control the sector naturally continue their careers in private sector agents that they have previously regulated, and by another, the risk of greater control of the public agenda by a private sector, which opted for vertical concentration and integration forming large oligopolies in contrast to the fragmentation and weakening of the public sector

A broad reflection on the design and implementation of the AUS policy in our country is necessary, before continuing to deepen its reform axes. The author considers that this policy did not find the decisive node to develop a reform in the health sector.

Those interested in health policies have the task of following successful experiences, such as "mental health reform." This policy established a reconfiguration of the programmatic dimension of mental health, established as a goal the achievement of health outcomes privileging effectiveness, guaranteed at the legislative level the rights of people with mental health problems, managed to articulate the allocative efficiency through the mechanism of Budgets for results and has been expanding the public offer of mental health services through a community care model.

The lesson is given, changing the old way of producing health to ensure universal access is possible and i more necessary than ever.

| Subsystem | Department | Before 2009 |

2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Period increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MINSA/ REGIONAL GOVERMENT |

Ayacucho | 414 | 420 | 424 | 426 | 426 | 427 | 427 | 427 | 428 | 428 | 429 | 15(4%) |

| Apurímac | 282 | 304 | 341 | 369 | 376 | 380 | 386 | 391 | 392 | 392 | 394 | 112(40%) | |

| Huancavelica | 324 | 348 | 390 | 401 | 405 | 408 | 413 | 414 | 414 | 414 | 415 | 91(28%) | |

| Lima Metropolitana |

376 | 381 | 384 | 388 | 395 | 398 | 398 | 399 | 402 | 404 | 409 | 33(9%) | |

| ESSALUD | Ayacucho | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 1(9%) |

| Apurímac | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 3(60%) | |

| Huancavelica | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0(0%) | |

| Lima Metropolitana |

27 | 35 | 38 | 42 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 17(63%) | |

| PRIVATE | Ayacucho | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 23 | 23 | 27 | 24(800%) |

| Apurímac | 16 | 22 | 23 | 30 | 56 | 68 | 76 | 85 | 90 | 96 | 97 | 81(506%) | |

| Huancavelica | 29 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 39 | 42 | 44 | 47 | 47 | 49 | 51 | 22(76%) | |

| Lima Metropolitana |

1436 | 1951 | 2446 | 2977 | 3783 | 4472 | 5042 | 5700 | 6101 | 6534 | 6829 | 5393(376%) |

Authorship Contributions: The author participated in the conception and design of the work; data collection / collection; statistical contribution; data analysis and interpretation; critical review of the manuscript; writing of the manuscript and approval of its final version.

Financing: Self-financed.

Interest conflict: The author declares no conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Received: December 2, 2018.

Approved: May 22, 2019.

Correspondence: David Jumpa Armas

Address: Jirón Domingo Cueto 109, Jesús María 15072, Lima-Perú

Telephone: 999070905

E-mail: david.jumpa@upch.pe