ORIGINAL ARTICLE

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2020 - Universidad Ricardo PalmaDOI 10.25176/RFMH.v20i4.2922

CHARACTERISTICS AND EVOLUTION OF PATIENTS WITH URINARY LITHIASIS IN EMERGENCY OF A TERTIARY HOSPITAL.

CARACTERÍSTICAS Y EVOLUCIÓN DE PACIENTES CON LITIASIS URINARIA EN EMERGENCIA DE UN HOSPITAL TERCIARIO

Waldo Taype-Huamaní1, Ricardo Ayala-García1,2, Ricardo Rodríguez-Gonzales1, José Amado-Tineo1,2

1Servicio de Emergencia de adultos, Hospital Rebagliati, Lima - Perú.

2Facultad de Medicina, UNMSM, Lima - Perú

Introduction: The symptoms and complications of urinary lithiasis are a frequent cause of emergency care. Objective: To determine the characteristics and evolution of patients with urinary lithiasis treated in the emergency service of a tertiary social security hospital. Methods: Observational study carried out at the Rebagliati hospital Lima-Peru, during the first quarter of 2019. Sociodemographic variables, time, and emergency indicators of the institutional statistical system were evaluated, performing descriptive statistics with IBM SPSS 25.0. Results: 583 visits were registered for urinary lithiasis (194 per month), corresponding to 14% of the genito-urinary pathology seen in the evaluated service. 55% male, average age 48 years (range 14 to 92). Mainly treated for topical surgery and priority 3, the most frequent causes of pain, infection, and hematuria. Time of first attention 4.8 hours, 70% leaving discharge. 10.5% were admitted to observation rooms with an average stay of 77 hours (3.2 days), 51% were hospitalized, 31% were discharged, 3% operated, and 2% died. Conclusion: Urinary lithiasis occurs in 1 out of 7 genitourinary pathology attentions of the emergency service evaluated, predominantly in men, of average age, 10% are admitted to the observation room, with short stay and low mortality.

Key words: Urolithiasis, Emergency Medical Services, renal colic, diagnosis.

Urinary lithiasis is the presence of stones in the urinary tract due to the formation or retention of organic or inorganic substances, its prevalence varies from 1 to 20% of the general population and the recurrence can be greater than 50% depending on geographical factors, climatic, ethnic, dietary and genetic(1,2). 11 to 13% of men and 7 to 9% of women will develop a kidney stone at some point in their life; on the other hand, approximately between 11 to 15% of men and 7 to 8% of women will experience symptoms suggestive of urolithiasis(3-5).

Around 1 million people with suspected urolithiasis go to emergency services each year in the United States of America(4), men experience renal colic in a ratio of 2: 1 compared to women(3). Pain is the main reason for admission in these patients, once the stone is formed, the size and location of the stone has the greatest effect on symptoms and patient management(6,-8).

Patients with uncomplicated urolithiasis, without the toxic appearance and controlled pain, are indicated for outpatient follow-up, and urological control is recommended in the case of stones ≥ 5mm or recurrent episodes. Those with suspected urinary tract infection, without fever, toxic appearance, or hydronephrosis can be discharged with antibiotics for a close consultation. On the other hand, evidence of sepsis, uncontrollable pain, intractable vomiting, single kidney, transplants, inability to follow-up, advanced age, evidence of obstruction, and serious medical comorbidities justify admission and evaluation by urology(1,3,9). Surgical indications have also been well established(2,10).

Urinary lithiasis is one of the most frequent reasons for emergency consultation and one of the institutional health priorities; affecting the quality of life and work performance of the population(2,11), but no publications were found in our environment, so we seek to determine the characteristics and evolution of patients with urolithiasis treated in the emergency service of a tertiary social security hospital, during the first quarter of 2019.

METHODS

A retrospective observational study carried out in the adult emergency service of the Hospital Nacional Edgardo Rebagliati Martins of EsSalud (Social Health Insurance) in Lima-Peru between January 1 and March 31, 2019, not including gynecological or psychiatric emergencies. This service performs more than 160 thousand services a year for people over 14 years of age(11).

The evaluated emergency service uses a structured triage system of 5 priorities (Manchester type), the patient who arrives is directed to an initial evaluation area: trauma-shock unit, medicine topics (priority 2 or 3 ), surgery, trauma, and relief (priority 4 or 5). For patients who are admitted (hospitalized in the emergency service) there are three critical care observation rooms and four general observation rooms.

The institutional statistical system was reviewed, selecting all the care with diagnoses N20 to N23 of the International Classification of Diseases version 10. Sociodemographic variables, arrival time, area of care, destination, and main emergency indicators were identified. The data were coded and processed in Microsoft Excel 2013. The descriptive statistical analysis and comparative graphics were carried out in IBM SPSS 25.0. Good research practice principles were followed.

RESULTS

During the first quarter of 2019, 583 visits for urinary lithiasis were reported, with an average of 194 per month and 6 daily visits. In the same period, 51294 visits were registered throughout the emergency service and 4284 with a first diagnosis related to genitourinary diseases. Therefore, urinary lithiasis represents 14% of the genitourinary pathology seen in emergency and 1% of the total care.

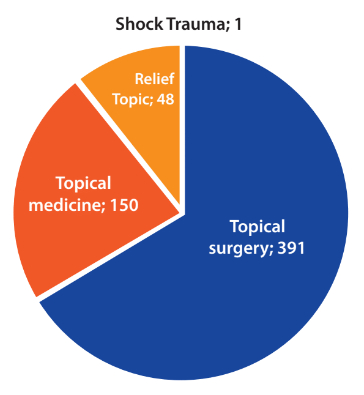

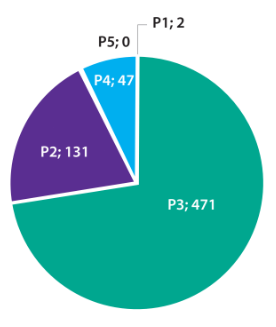

55% of those attended were male, with an average age of 48 years (range between 14 and 92 years), the distribution according to the topic of care is shown in Figure 1 and their priority of care upon admission to an emergency in Figure 2. The most frequent reasons for consultation were renal colic, low urinary discomfort, and hematuria. The time spent in the emergency room until the end of their first care was 4.8 hours (range between 0.1 and 22), their destination is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1. Initial care topic of patients with urinary stones who attend the HNERM adult emergency service, January-March 2019.

Figure 2. Initial care priority of patients with urinary stones who attend the HNERM adult emergency service, January-March 2019.

Table 1. Fate of patients with urolithiasis treated in the emergency adult HNERM, January-March 2019.

| Destination | Attentions | % |

| Withdrawal | 409 | 70% |

| Other Service | 86 | 15% |

| Observation Room | 61 | 11% |

| Exit or voluntary discharge | 14 | 2% |

| Returns | 13 | 2% |

| Total | 583 |

10.5% of care were admitted (hospitalized) in emergency observation rooms, corresponding to 20 monthly admissions and 5 weekly admissions. The most frequent diagnoses were persistent pain 53%, urinary infection 32%, and acute renal failure 8%. 46% were male and the average age was 50 years (range 25 to 88). These patients spent an average of 3.2 days in the emergency room (standard deviation 2.66) equivalent to 77 hours; the destination of these admissions is presented in Table 2. The deceased patient corresponded to an adult older than 76 years with diabetes mellitus and long-standing arterial hypertension who was admitted to the intermediate care unit due to urinary starting point sepsis and developed multiple organ failure.

Table 2. Destination of patients with urinary stones admitted to HNERM adult emergency observation rooms, January-March 2019.discharge.

| Destination | Admissions | % |

| Floor | 31 | 51% |

| Discharge | 19 | 31% |

| Return | 4 | 7% |

| Voluntary | 2 | 3% |

| Critical areas | 2 | 3% |

| Operating room | 2 | 3% |

| Dead | 1 | 2% |

| Total | 61 |

DISCUSSION

Urinary lithiasis is a frequent cause of consultation in the emergency service. In the evaluated hospital, around 190 monthly visits are made for this problem, corresponding to 14% of emergency genitourinary pathology. The population prevalence of this pathology is highly variable, increasing in the last decade, but it is not defined in our region(1,10).

Urinary lithiasis predominates in men, similar to international reports, but in a lower proportion than the 4: 1 found in Spain(7,8,12). Age was also similar to the average of 42 years reported for the first clinical manifestation, remembering that the presence of renal colic or hematuria in people over 60 years of age makes it necessary to seek another diagnosis(5).

Other factors associated with this pathology such as diet and lifestyle that cause them to occur in younger patients, mainly obesity and diabetes mellitus (also in women) were not evaluated in the present study(10).

Regarding the form of presentation of urinary lithiasis, the most frequent is renal colic, similar to that found in the present study. It is reported that the intensity of pain was severe (score from 7 to 10 according to an intensity scale of 1 to 10) referring to the right side in 56% of cases(7).

Regarding the time of year, a higher incidence of renal colic has been reported in summer or spring and a lower number of emergency visits in winter; This agrees with the time evaluated in the present study. Associating with arid and high-temperature areas, postulating some relationship with the global warming phenomenon that occurs in the world(7,10).

70% are discharged after the first attention in the emergency service, in accordance with the literature, where recurrences are reported 24% of patients at 6 months and 50% at 5 years, mentioning that the majority of cases Those who visit the emergency are resolved spontaneously or with medical treatment in three days, but we do not have local studies(2,8).Mentioning ultrasound as a non-invasive and low-cost study that helps to decide discharge(1,4).

The most used analgesic treatment in Spain (2006-2008) was metamizole and ketorolac(8). Although it is true that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) act on the inflammatory condition triggered by urinary lithiasis, opioid analgesics such as tramadol or morphine are also recommended in severe cases or when NSAIDs cannot be used(5,9,12).

Another medical treatment option is drugs that decrease urinary tract smooth muscle tone such as tamsulosin (an alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonist) or nifedipine (a calcium antagonist)(5,9,12). Bearing in mind that there are defined indications with an adequate level of evidence for the surgical treatment of urolithiasis(2,3,5).

One out of every five patients who come to the emergency room for urolithiasis is admitted to the emergency observation room (an average of three days), the most frequent reasons being a pain, infection, and kidney involvement, presenting low mortality (less than 2%).

Similar to other reports where they indicate infection, hematuria, and urinary tract obstruction (hydronephrosis) as the most frequent complications. It should be noted that it is important to bear in mind possible differential diagnoses according to each case(3-5,8) and in most cases in hydronephrosis, hematuria does not occur, so the urine test would be normal(13).

Among the limitations of the study we have the fact of evaluating a single hospital and a quarter of the year, the data are recorded by non-medical personnel asynchronously, without specifying specific causes, location, comorbidities, and treatment used. The diagnoses are not uniform, part of the care was not electronic. However, it includes a significant number of services that could represent the reality of hospitals with similar characteristics nationwide.

Finally, it is concluded that urinary lithiasis occurs in 1 out of 7 genitourinary pathology attentions of the emergency service of the evaluated hospital, predominating renal colic and infection in men with an average age of 48 years. 1 out of 5 patients treated for urinary lithiasis was hospitalized, with a short stay and low mortality.

Author’s Contributions: : The author participated in the genesis of the idea, project design, data collection and interpretation, analysis of results, and preparation of the manuscript of the present research work.

Funding: Self-financed.

Conflicts of interest: The author declares no conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Received: March 25, 2020

Received: May 25, 2020

Correspondence: José Percy Amado Tineo

Address: Jr Belisario Flores 238 Dpto 301 Lince-Lima

Telephone: 990452547

Email: jpamadot@gmail.com

REFERENCES