ARTICULO ORIGINAL

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2021 - Universidad Ricardo Palma10.25176/RFMH.v22i2.4787

CURRENT STATUS OF GENERAL RESOURCES AND OPERATION OF HOSPITAL SERVICES FOR PEDIATRIC EMERGENCIES WITH PUBLIC MANAGEMENT IN LATIN AMERICA (STUDY RFSEPLA)

ESTADO ACTUAL DE RECURSOS GENERALES Y FUNCIONAMIENTO DE SERVICIOS HOSPITALARIOS DE EMERGENCIAS PEDIÁTRICAS CON GESTIÓN PÚBLICA EN LATINOAMÉRICA (ESTUDIO RFSEPLA)

Liliana Cáceres1,a, Anabella Boto1,b, Sandra Cagnasia2,b, Laura

Galvis3,c, Pedro Rino1,b, Adriana Yock-Corrales4,d, Carlos

Luaces5,c

1Hospital de Pediatría Juan P. Garrahan, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires-Argentina

2Hospital de Niños Victor J. Vilela-Argentina

3Fundación Valle de Lili. Cali-Colombia

4Hospital Nacional de Niños ¨Dr. Carlos Sáenz Herrera¨, CCSS. San José-Costa Rica

5Hospital Sant Joan de Déu. Barcelona-España

aPediatrician and emergentologist

bPediatric emergentologist

cEmergency Pediatrician

dEmergencioligist Master in Epidemiology

eEmergency Pediatrician

ABSTRACT

Introduction: To improve the quality of care in Pediatric Emergency Departments (PEDs), it is essential to carry out measurements and surveys. Purpose. To describe the resources and operation of PEDs of public hospitals in Latin America. Methods: A retrospective, quantitative and descriptive study was conducted in 2019, consisting of a survey administered to PEDs of Latin-American public hospitals that have a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). Data were processed using REDcap and InfoStat programs. Continuous variables are presented as median and range, categorical variables as percentages, and productivity/resource relationships as ratios. Univariate analysis was performed. Results: Of 371 PEDs in 17 countries, 107 (28.8%) answered the survey. A total of 102 departments (95.3%) have an observation area and 42 (39.3%) have isolation rooms. Median number of annual visits/observation beds and daily visits/office were 4830.6 and 24.4, respectively. Overall, 6.1% of the patients required hospitalization and 2.0% were assisted in the Resuscitation Area. 37 PEDs (34.6%) have more than 80% of 27 items considered essential by the International Federation for Emergency Medicine; 43 PEDs (40.2%) have incomplete airway equipment and 74 (69.2%) perform triage. The median number of daily visits is 38.4/physician and 35.3/nurse. Electronic records are used in 83 (77.6%) PEDs and 68 (64,1%) use five protocols for critical situations; in 10 (9.4%) time is allocated to teaching and research and in 43 (41%) there is quality improvement plan. Conclusions: The information obtained regarding resources and operation of public PEDs in Latin America reveals important gaps.

Keywords:Pediatric Emergency Departments;Quality of Health Care; Preparedness; Surveys and Questionnaires; Health Resources.(fuente: MeSH NLM).

RESUMEN

Introducción: Para mejorar la calidad de atención en los Servicios de Emergencias Pediátricas (SEP), es indispensable realizar mediciones y relevamientos. Objetivo: Describir los recursos y funcionamiento de los SEP de hospitales públicos de Latinoamérica. Métodos: Estudio descriptivo, cuantitativo y retrospectivo. Encuesta realizada en SEP de hospitales latinoamericanos con financiación pública y con Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos (UCIP) (2019). Datos procesados mediante programas REDcap e InfoStat. Se presentan variables continuas como medianas y rangos; variables categóricas, como porcentajes; relaciones de productividad/recursos como razón. Se realizó análisis univariado. Resultados: De 371 servicios en 17 países, 107 (28,8%) contestaron la encuesta. Ciento dos servicios (95,3%) tienen sector de observación y 42(39,3%), salas de aislamiento. La mediana de consultas anuales/cama de observación fue 4830,6; la mediana de consultas diarias/consultorio 24,4. 6,1% de las consultas requirieron internación y 2,0% fueron asistidas en el Sector de Reanimación. Treinta y siete SEP (34,6%) disponen de > 80% de 27 ítems considerados imprescindibles por la Federación Internacional de Emergencias; 43 SEP (40,2%) carecen de equipo completo de vía aérea. En 74 servicios (69,2%) se realiza triaje. La mediana de consultas diarias es de 38,4/médico y 35,3/enfermero. En 83(77,6%) centros se manejan datos informatizados. En 68 SEP (64,1%) se utilizan cinco protocolos de situaciones críticas. En 10(9,4%) el personal médico cuenta con horario de docencia/investigación. Existe plan de mejora de calidad en 43 (41%) servicios. Conclusión: La información obtenida sobre los recursos y funcionamiento de los SEP públicos en Latinoamérica revela brechas importantes.

Palabras Clave: Medicina de Urgencia Pediátricas; Calidad de la Atención de Salud; Preparación; Encuestas y cuestionarios;Recursos en Salud.(fuente: DeCS BIREME).

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric emergency and urgent care have increased over the last 30 years, leading to the need to adapt in order to provide quality care, dened by the WHO as “the degree to which the health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes”; quality health services should be "effective,safe,people-centred,timely,equitable, integrated and efficient"(1).Health agencies from different countries and international institutions have developed standards and indicators to improve the quality of care in PEDs(2,10). It is essential to carry out measurements and surveys to know the status, needs, and opportunities for improvement(11-17); so far, such studies have not been published in Latin America.

OBJECTIVE

This study aims to describe the general resources and operations of SEPs in publicly managed hospitals in Latin America.

METHODS

Study design type and area

A retrospective, cross-sectional, quantitative, descriptive study was conducted consisting of a survey to collect data on the structure and operation of PEDs in Latin America in 2019.

Population and sample

The survey was sent to the chairs of PEDs of Latin America public hospitals. Since hospital complexity is classified differently in the countries of the region and to focus on the institutions that offer the best possibility of developing the specialty of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, public hospitals thathaveapediatric intensive care unit (PICU) and are nanced entirely or partially by the public sector were included. Centers that did not send the Condentiality Agreement(CA) signed by the hospital director or the head of the Research Committee were excluded.

Instrument and variables

The assessment instrument was a survey based on documents,questionnaires,and reports of quality indicators published by national and international agencies(9,10,12,14) and was subsequently revised by experts in Pediatric Emergency Medicine belonging to the Safety and Quality Committee of the Sociedad Latinoamericana de Emergencias Pediátricas (SLEPE) and the Red de Investigación y Desarrollo de la Emergencia Pediátrica Latino americana(RIDEPLA). Data on productivity and physical, human, regulatory, and management resources for 2019 were collected. The survey consisted of 133 questions grouped into 8 sections:institutional information, facilities, equipment, electronic records and online resources, human resources,available specialist consultation, teaching and research activity,emergencycare protocols, and quality and safety procedures.

The research team included 28 On-site Collaborators (OC)from 17 Latin-American countries.The OCs prepared the lists of hospitals that met the inclusion criteria in their countries, contacted the chairs of the PEDs,and accompanied the respondents in the processes of signing the CA and data collection.

Analysis of data

The data collection and analysis was carried out on the REDCAP platform (Research Electronic Data

Capture: https://www.project-redcap.org), and the InfoStat version 2020 program was also used for data

analysis (National University of Córdoba, Argentina: http://www.infostat.com.ar) was used.

The normality of the distribution of quantitative data was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. None

of the continuous variables showed normality; therefore, the medians and interquartile ranges are

reported. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. For between-group comparison

the Chi-square test was used. The level of significance was set at 0.05. Relationship between healthcare

productivity data and structural resources was reported as ratios.

Ethical Aspects

The study protocol, the survey, and the ACI were approved by the Research and Ethics Committees of Hospital Garrahan and sent to the heads of the SEPs. Once the ACI was signed by the General Director of each hospital or by the head of the Research Committee, the survey was sent online through the REDCap program. The study was conducted from December 1st, 2019 to December 8th, 2020.

RESULTS

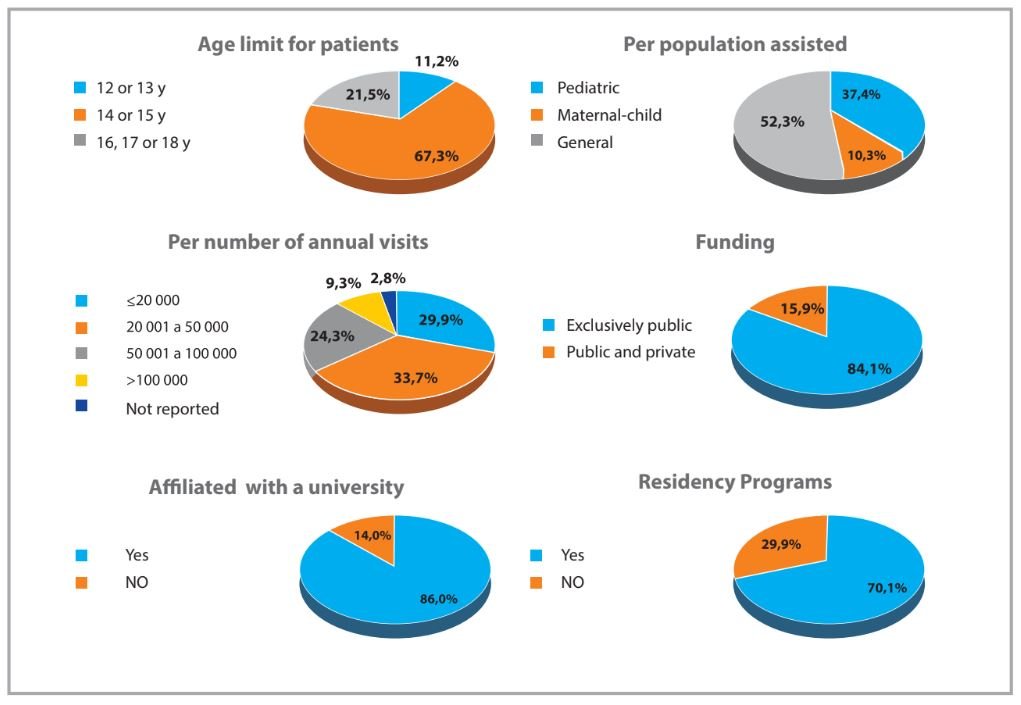

Institutional information

Table 1 shows the number and percentage of hospitals identified, contacted, and participating in each country. Contact could not be established with the SEP of Haiti, Cuba, and Venezuela.

Table 1. Hospitals and participants identified by country

| Country | Identified / contacted n / n | Responded - (% of total identified) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 66 / 66 | 63 (95) |

| Bolivia | 8 / 8 | 7 (88) |

| Brasil | 161 / 70 | 1 (0,0) |

| Chile | 25 / 16 | 3 (12) |

| Colombia | 6 / 6 | 1 (17) |

| Costa Rica | 1 / 1 | 1 (100) |

| Ecuador | 4 / 4 | 3 (75) |

| El Salvador | 3 / 2 | 2 (66,7) |

| Guatemala | 1 / 1 | 1 (100) |

| Honduras | 2 / 2 | 1 (50) |

| México | 57 / 38 | 13 (22,8) |

| Nicaragua | 1 / 1 | 0 (0) |

| Panamá | 3 / 3 | 1 (33) |

| Paraguay | 7 / 7 | 5 (71) |

| Perú | 22 / 21 | 3 (13,6) |

| República Dominicana | 1 / 1 | 1 (100) |

| Uruguay | 3 / 3 | 1 (33) |

| TOTAL | 371 / 250 | 107 (28,8) |

Hospital supplies and services. A total of 104 hospitals (97.2%) have a central oxygen delivery

system and 99 (92.5%) a central vacuum system; 24-hourlaboratoryandpharmacyservicesare available in 105

hospitals (98.1%) and 65 hospitals (60.7%), respectively. Around-the-clock diagnostic imaging

availability is as follows: simple radiology in104(97.2%),computedtomographyin88 (82.2%), and magnetic

resonance imaging in 19 hospitals (17.8%).

specific functions assigned by the hospital. The surveyed PEDs

areresponsiblefortheregional interhospital transport system in 46 (43%) hospitals, for the operation of

the rapid response team in 61 centers (57%), and for the hospital evacuation plan in 71 (66.4%)

institutions.

Infrastructure and functionality.

The available facilities are described in Table 2 and the functionality related to

the care process in Table 3.

Table 2. Facilities - description (n: 107)

| Areas | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Entrance and reception area | |

| Independent entrance for ambulances | 85 (79,4) |

| Security personnel at the entrance | 96 (89,7) |

| Differentiated WR according to patient severity | 25 (23,4) |

| Different WR for children and adults (n: 67) * | 39 (58,2) |

| Patient care areas | |

| Observation Room | 102 (95,3) |

| Pediatric OR separated from adult OR (n: 67) * | 55 (82) |

| Pediatric RA separated from adult SR (n: 67) * | 43 (64,2). |

| Isolation room with a private bathroom | 42 (39,3) |

| Private area for interviews | 37 (34,6) |

| Room for inhalation therapy | 62 (57,9) |

| Room for oral rehydration | 45 (42,1) |

| Room for procedural sedation | 36 (33,6) |

| Room for minor procedures | 78 (72,9) |

| X-ray room or equipment (own or adjacent) | 71 (66,4) |

| Classroom available in the PED or in the hospital (n: 106) | 101 (95,3) |

Table 3. Care process and functionality of the infrastructure

| Care process (n: number of hospitals that answered the data) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. Triage | n (%) | |

| They have Triage (n:107) | 74 (69,2) | |

| Triage 24/365 (n:74) | 60 (81,1) | |

| Computerized triage (n:74) | 47 (63,5) | |

| 2. Functionality of the physical plant | Median (RI) | |

| Daily consultations per office (n: 106) | 24,4 (14,7- 49,1) | |

| Percentage of patients treated in the SR (n: 87) | 2,0 % (0,9% – 5,8%). | |

| Number of beds in the SO (n:107) | 6 (4-14) | |

| Annual consultations per bed in the SO (n:100) | 4830,6 (2200 – 9125,5) | |

| Percentage increase in beds at seasonal peak (n:107) | 74,1% (28,6% - 150%). | |

| 3. Time of care | ||

| Time of outpatient care (n:29) | 2 (1-4) horas | |

| Time of stay in OS (n: 49) | 10 horas (6 - 24) | |

| Length of stay in SR (n: 37) | 2 horas (1 - 3) | |

| 4. Hospitalization | ||

| Percentage of hospitalized patients (n: 94) | 6,1%; (3,8% – 16,2%). | |

Triage: Patients who withdraw without having been seen are reliably registered in 28 SEP (26.2%)

and incompletely or partially in 43 centers (40.2%); they are not registered in 36 hospitals (33.6%).

Observation sector: In 58 SEP (54.2%), there is a regulation of maximum time of stay of

patients in the OS, whose median is 12 hours (IR 6-24 hours).

Equipment:

Figure 2 describes the resources and their availability in the Resuscitation Area.

The airway equipment considered essential by the International Federation for Emergency Medicine8 was surveyed as a whole. In 43 PEDs (40.2%), airway equipment was reported to be incomplete. Thirty-seven departments (34.6%) have an ultrasound scanner and 21 (19.6%) an End- tidal CO2 monitor.

Table 4. Registries and resources online(n: 107)

| Item | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Electronic general records | 83 (77,6) |

| Electronic medical records | 51 (47,7) |

| 24-hour available medical records* | 71 (66,4) |

| Diagnostic coding system in the PED | 82 (76,6) |

| Discharge form | 91 (85) |

| Digital images | 63 (58,9) |

| Model templates for frequent diseases | 23 (21,5%) |

| Hospital protocols and guidelines | 47 (43,9) |

| Drug alert system | 16 (15) |

| Tracking of patients in the PED | 30 (28) |

Coding is performed by doctors in 47 departments (56.8%), by administrative personnel in 34 (42%), and by nurses in 1 hospital (1.2%).

Human Resources

Different human resources and their functions are shown in Table 5.

Tabla 5.Human Resources

| They have their own / exclusive SEP staff * (n: 106) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Medical staff | 65 (61,3) |

| Medical Coordinator | 61 (57,5) |

| Nursing Coordinator | 71 (67) |

| Secretary | 52 (49,1) |

| Social worker | 22 (20,8) |

| Respiratory therapist | 15 (14,2) |

| Pharmacist | 11 (10,4) |

| Training and access to specialties (n hospitals that responded to the data) | |

| They have 4 primary full-time specialties (n: 106) | 40 (37,4) |

| Functionality (n hospitals that answered the data) | |

| n hospitals that answered the data | 63 (59,4). |

| The number of doctors is adapted to the demand (n: 107) | 64 (59,8) |

| The number of nurses is adapted to the demand (n: 107) | 70 (65,4) |

| Median (RI) | |

| Daily visits per doctor(n:103) | 38,4 (20,6 – 53,2) |

| Daily visits per nurse (n: 102) | 35,3 (13,6 – 59,6) |

Median number of daily visits per physician is greater than 65 in 16 PEDs (15.6% of 103 that reported

the data); median number of daily visits per nurse is greater than 65 in 22 centers (21.6% of 102

responses).

Previous training

Overall, pediatricians account for 76% of the PED staff (1903

pediatricians out of 2502 physicians); 49.6% are certied in Pediatric Emergency Medicine or have more

than 5 years of experience in the specialty.Family physicians, general practitioners, or clinicians

represent 11% and adult emergency physicians 7.8% of the staff.

Support services

Biochemical technicians or specialists are 24/7 available in 84

centers (79.2%), hemotherapy technicians in 82 (78.1%), and pharmacists in 29 (27.4%).

Teaching and research activity and emergency care protocols

Daily rounds take

place in 96 (90.6%) and grand rounds in 41 departments (38.7%). There is a continuous training program

for doctors in 36 (34.0%) and for nurses in 44 PEDs (41.5%). Of 74 hospitals where triage is performed,

58 (78.4%) provide training in triage. In 10 centers (9.4%) doctors have specic time for teaching and

research and so have nurses in 13 hospitals (12.3%).Physicians from 48 departments(45.3%)have presented

scientic studies at congresses over the last ve years, and in the same period, physicians from 26

(24.5%) have published research papers.

On-site training programs.

Eleven hospitals (10.4%) have a Pediatric Emergency

Medicine training program (residency, fellowship, or other),while 92 PEDs(86.8%)receiverotationsof

resident doctors. Sixty-eight departments (64.1%) have protocols or clinical guidelines fo rCPR,shockand

sepsis,respiratory failure,status epilepticus,and trauma. Forty PEDs (37.7%) have a disaster protocol

that includes pediatric needs.

Table 6.Univariate analysis

| Per population assisted | Per funding | Per number of annual visits * | Per affiliation with a university | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Pediatric/Maternal-Child | p value | Exclusively Public | Public and private | p value | ≤ 50.000 (NCA1) | 50.001 to 100.000 (NCA2) | > 100.000 (NCA3) | p value | Affiliated | Not affiliated | p value | |

| Distribution of hospitals - per listed category | 56 (52,3) | 51 (47,7) | 0.629 | 90 (84,1) | 17 (15,9) | <0,001 | 68 (65,4) | 26 (25,0) | 10 (9,6) | <0,001 | 75 (70,1) | 32 (29,9) | <0,001 |

| Functionality of infrastructure | |||||||||||||

| Daily visits per medical office | 20,6 (27,0) | 33,7 (43,7) | 0.02 | 26,2 (34,6) | 21,3 (38,1) | 0.689 | 19,6 (24,2) | 46,5 (55,7) | 52,5 (62,1) | <0,001 | 22,1 (34,6) | 30,3 (36,5) | 0.732 |

| Annual visits per observation bed | 5207,5 (6537,1) | 4998,8 (7788,9) | 0.868 | 4830,5 (7135,6) | 6461,5 (7328,9) | 0.362 | 3666,7 (6077,5) | 6464,1 (8358,1) | 7212,7 (11955,6) | <0,001 | 4500,0 (6602,2) | 6464,1 (8321,7) | 0.291 |

| Complete airway equipment | 23 (41,1) | 20 (39,2) | 0.845 | 38 (42,2) | 5 (29,4) | 0.323 | 29 (42,6) | 9 (34,6) | 2 (20,0) | 0.349 | 30 (40,0) | 13 (40,6) | 0.952 |

| Care process | |||||||||||||

| Triage | 33 (58,9) | 40 (78,4%) | 0.03 | 62 (68,9) | 11 (64,7) | 0.734 | 44 (64,7) | 17 (65,4) | 10 (100) | 0.076 | 56 (74,7) | 17 (53,1) | 0.028 |

| % increase in beds in seasonal peak | 100 % (161,8%) | 60% (107,7%) | 0.227 | 75,0 % (143,2%) | 66,7% (93,6%) | 0.458 | 75,0% (137,9%) | 66,7% (123,5%) | 70,4 %(122,0%) | >0,999 | 75,0% (143,6%) | 83,3 %(115,9%) | 0.929 |

| % of admitted patients | 4,3% (8,2%) | 8,7% (15,2%) | 0.008 | 6,4% (13,5%) | 4,3 %(5,01%) | 0.046 | 6,9% (15,1%) | 3,9% (6,0%) | 5,2% (7,1%) | 0.079 | 6,7% (12,1%) | 4,5% (11,7%) | 0.499 |

| % of patients assisted in the RA | 1,4% (3,7%) | 1,9 (3,7%) | 0.299 | 6,4 % (13,5%) | 4,3% (5,01%) | 0.046 | 1,9% (4,3%) | 1,6% (2,7%) | 0,9% (2,9%) | 0.498 | 1,7% (4,0%) | 1,4 % (3,0%) | 0.64 |

| Human resources | |||||||||||||

| Physician or nurse PECC in each sift | 35 (63,6) | 37 (72,5) | 0.326 | 61 (68,5) | 11 (64,7) | 0.756 | 45 (66,2) | 18 (72,0) | 7 (70,0) | 0.858 | 57 (76,0) | 15 (48,4) | 0.006 |

| Daily visits per physician | 32,2 (32,2) | 46,2 (48,5) | 0.003 | 40,2 (41) | 32,2 (36,8) | 0.567 | 30,1 (29,9) | 58,5 (60,9) | 66,6 (66,3) | <0,001 | 41,6 ( 43,7) | 33,3 (32,5) | 0.063 |

| Daily visits per nurse | 32,4 (38,3) | 43,4 (44,1) | 0.225 | 37,5 (42,5) | 34,4 (34,5) | 0.532 | 20,6 (29,9) | 62,5 (65,0) | 61,1 (64,4) | <0,001 | 39,3 (44,8) | 33,4 (32,8) | 0.107 |

| Records | |||||||||||||

| Electronic general records | 42 (75,0) | 41 (80,4) | 0.504 | 70 (77,8) | 13 (76,5) | 0.906 | 48 (70,6) | 23 (88,5) | 9 (90,0) | 0.108 | 57 (76,0) | 26 (81,3) | 0.551 |

| Teaching activities | |||||||||||||

| Grand rounds | 16 (29,1) | 25 (49,0) | 0.035 | 32 (36,0) | 9 (52,9) | 0.188 | 24 (35,3) | 10 (40,0) | 7 (70,0) | 0.112 | 30 (40,0) | 11 (35,5) | 0.664 |

| Training program for doctors | 10 (18,2) | 26 (51) | <0,001 | 32 (36,0) | 4 (23,5) | 0.322 | 25 (36,8) | 6 (24,0) | 5 (50,0) | 0.299 | 29 (38,7) | 7 (22,6) | 0.1117 |

| Training program for nurses | 15 (27,3) | 29 (56,9) | 0.002 | 35 (39,3) | 9 (52,9) | 0.297 | 26 (38,2) | 11 (44,0) | 7 (70,0) | 0.164 | 32 (42,7) | 12 (38,7) | 0.707 |

| Quality of Care | |||||||||||||

| Competency evaluation for physicians | 10 (18,2) | 16 (32,0) | 0.101 | 23 (26,1) | 3 (17,7) | 0.458 | 18 (26,5) | 3 (12,5) | 5 (50,0) | 0.069 | 22 (29,7) | 4 (12,9) | 0.068 |

| Competency evaluation for nurses | 11 (20,0) | 17 (34,0) | 0.105 | 25 (28,4) | 3 (17,7) | 0.358 | 21 (30,9) | 4 (16,7) | 3 (30,0) | 0.399 | 23 (31,1) | 5 (16,1) | 0.114 |

| QI committee | 27 (49,1) | 30 (60,0) | 0.262 | 46 (52,3) | 11 (64,7) | 0.346 | 38 (55,9) | 11 (45,8) | 6 (60,0) | 0.642 | 44 (59,5) | 13 (41,9) | 0.1 |

| QI plan | 17 (30,9) | 26 (52,0) | 0.028 | 35 (39,8) | 8 (47,1) | 0.576 | 30 (44,1) | 6 (25,0) | 7 (70,0) | 0.045 | 34 (45,9) | 9 (29,0) | 0.108 |

* PED´s that receive >100.000 annuals visits were compared to those which receive ≤ 100.000 annual visits

PECC: Pediatric Emergency Care Coordinator. QI: Quality Improvement

DISCUSSION

Pediatric Emergency Medicine has progressively expanded in Argentina and Latin America since it was

first recognized in Mexico in 2006 and has gained momentum in recent years with the creation of the

Latin American Society of Pediatric Emergencies and Committees of Pediatric Emergencies both in

Pediatric societies and in Emergentology societies of numerous Latin American countries (18).

In many countries, recognition of the specialty has contributed to the development of this

medical eld and has encouraged healthcare teams to join efforts to improve care results(18-20). The aim of this study was to assess the current state of resources

and operation of PEDs of public hospitals in Latin America and, thereby, to contribute to the

identication of opportunities for improvement.

The following observations and comments are based on Argentine regulation (21) and recommendations from agencies from different countries that represent

a references for te design of quality improvement programs(2-10,22).

Infrastructure and equipment.

The equipment of the Resuscitation Area was found to be

decient in many PEDs. The complete list of essential elements for airway management is available in only

59.8% of the departments. According to international standards, different aspects of the waiting rooms

and sectorized areas for pediatric care are decient as well(8).

The Spanish Society of Pediatric Urgencies(SEUP) recommends to have one office for every

(16-22) daily visits. (6) In the

surveyed hospitals, median daily visits per office exceeded the maximum recommended number, and the

interquartile ranges show that there is a paucity of offices in many departments. Univariate analysis

showed that this decit is more signicant in pediatric and maternal-child hospitals, and in PEDs that

receive more than 100 000 visits per year (category NCA3). The number of visits per observation bed was

also signicantly higher in NCA3 category departments.

Care process.

The use of triage was signicantly associated with the categories of

pediatric and maternal-child hospital and university hospital.

Human Resources.

Unlike other specialties in which physicians work exclusively in

their area of expertise,only 61.3%of hospitals hire professionals exclusively for the PED.Astrong

international recommendation is for PEDs (especially those in general hospitals) to have a physician and

nurse PECC per shift to ensure the quality of pediatric care (8); currently,

32.1% of the PEDs lack these PECCs, and no difference was found between hospital categories.

According to international standards, the number of staff should be established based on the

demand and the case-mix. It has been determined that a doctor or a nurse sees between 2.5 and 2.7

patients per hour (65 daily visits) (6,23).

Our data suggest a generalized work overload, especially in shift swith a higher demandand in

departments that do not adapt the number of staff to the demand ows. This opportunity for improvement is

greater in pediatric and maternal-child hospitals and NCA3 category hospitals.Determining the

characteristics of the patient ow and the “ngerprint”of their demand would allow PEDs to calculate the

human resources and its temporal distribution based on the number and severity of the patients (24).

The seasonal over-demand is evidenced in the increase in beds available in most hospitals during

the seasonal peak (25); This data supports the importance of having triage

systems with qualified personnel.

Overall, 76% of the staff members are pediatricians. It is encouraging to see that approximately

half of these specialists are certified in Pediatric Emergentology or have 5 years of experience and

training in the specialty.

Taking into account the complexity of the surveyed hospitals, it is striking that only 37.4%

have a permanent surgeon, traumatologist, pediatric intensivist, and anesthesiologist. In 3 maternal and

child hospitals, the obstetricians are present part-time or at call. The limited accessibility of

specialists in Respiratory Endoscopy makes it necessary to consider the training of schools in the

management of difficult airways and the provision of the required equipment.

The high percentage of hospitals that do not provide 24/7 support by biochemical

technicians/specialists and hemotherapy technicians deserves attention. In addition, the pharmacy

department has become an important aid for the healthcare area; however, only 27.4% of hospitals have a

pharmacist around the clock.

Teaching and research activities.

Training programs for both doctors and nurses are

scarce; when comparing by categories, a signicantly higher percentage of programs was found in pediatric

and maternal-child hospitals versus general hospitals. Clinical grand rounds were also signicantly

associated with the condition of children's hospital. Triage training is carried out in 78.4% of the

PEDs; it is recommendable to train all the personnel who perform this task.

We observed that few PEDs presented or published research studies and very few centers allocate

time to teaching or research.

A considerable percentage of PEDs have protocols for the care of critical patients. On the other

hand, few hospitals have protocols for disasters that consider pediatric needs, similar to ndings

reported by surveys carried out in other regions of the world(11,26).

Noteworthy,many of the PEDs are in charge of interhospital transport and disaster response.

Considering the organizational and professional training limitations of prehospital emergency services

in Latin America, training in these medical elds and the development of clinical guidelines deserves

special attention(27,28).

Quality and safety management.

Surveys carried out in the US and Europe shows that

one of the most constant gaps is the absence of quality and safety improvement plans (11,26). In this study that analyzes the most complex

hospitals in our region, we observed that a limited percentage of them (54.3%) have a QualityCommittee

and Safety. Less than half of the SEPs have a continuous improvement plan of Quality. When analyzing by

categories, it was observed that quality improvement plans are significantly associated with the

condition of a children's hospital and the category of hospitals with the highest demand.

Long shifts in a setting of work overload are associated with an increased risk of medical

error. In addition to adapting the number of staff and promoting continuous education, quality and

safety programs or tools(29) should be in place and incorporated into the

medical curriculum(30).

Development of a continuous QI plan is recommended together with the designation of a member of

the staff in charge of quality management, as well as the use of a Quality Indicator Dashboard as a

management tool to measure, prioritize, plan, and sustain quality and safety interventions, and to

report to the hospital authorities.

We emphasize the importance of defining specic competencies for PE physicians and nurses and

assigning medical and nursing PECCs. These roles have been shown to be strongly associated with better

preparedness of the PEDs(11).

We found opportunities for improvement in issues of patient safety,including the recording of

adverse events, the use of tapes for calculating weight, and the introduction of tools to prevent

medication errors.

Support from the hospital management will be important to establish protocols for the

maintenance of medical equipment, to dene criteria for accepting and rejecting referrals,and to ensure

access to on-line medical information.

Limitations of the study

This study has some limitations. Not all contacted centers answered the survey, which may have

reduced the validity of the results. In addition, this study was conducted in public hospitals only and

excluded centers with private management contracted by the public health care system,which is a common

health care modality in different countries,suchas Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. Therefore, these

countries were under-represented in the study. Moreover, the results may have been strongly inuenced by

the specic conditions of the PEDs in Argentina, which represent 58.9% of the sample, while in some

countries of Central America only a single center met the inclusion criteria. Further research including

larger and more representative samples from all countries will be necessary to identify changes that

occurred in the PEDs during the COVID-19 pandemic.Despite these limitations, this study is a first

approach to understanding the current status of PEDs in Latin America.

CONCLUSION

The information obtained on the resources and operation of public PEDs in Latin America reveals important gaps. Furthermore, it is necessary to program interventions to improve the quality of care and promote monitoring of quality indicators.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the chief physicians of the Emergency services for their participation, and the

following collaborating physicians on the site, who played an important role in disseminating and

specifying the survey process.

Clavijo, Manuel; Maliarchuk, Otto; Mousten, Barbara; Santos, Caesar; Vilar, Julieta; Mary

Tejerina; Moura, Bruno; Saa Fernanda, Hany Simon Junior; Brother-in-law, Pamela; Olivares Jorge; Estrada

Monterrosa, José María; Rojas Balcázar, Carlos; Rubio Vélez, Nataly; de la O Cáceres, Francisco; Álvarez

Gálvez Eugenia; Figueroa-Uribe, Flavio; Olivar, Victor; Mendoza León, Barros Angélica, Pineda Rommy,

Amaya, Gerardo; Rodríguez, Leónidas; Pavlicich, Viviana; Luna-Muñoz Consuelo; Pezzo, Jaime; Corona,

Lisandra; More, Mariana.

Authorship contributions: All the realization of this work was carried out by the

authors, there was no intervention of people or institutions that have financed or had any

participation in the article.

Funding sources: : This study did not have a source of financing.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Received: November 13, 2021

Approved: December 15, 2021

Correspondence: Liliana Cáceres

Address: Hospital de Pediatría Prof. Dr. Juan P. Garrahan, Combate de los Pozos 1881.

(CP 1245 AAM) C.A.B.A. República Argentina.

Telephone number: (+54-11) 4122-6000

E-mail: lcaceres.sae@gmail.com

REFERENCES