CLINICAL CASE

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2024 - Universidad Ricardo Palma10.25176/RFMH.v24i1.6099

HEART FAILURE SECONDARY TO A SNAKE BITE. THE INTENSIVIST'S VISION: CASE REPORT

INSUFICIENCIA CARDÍACA SECUNDARIA A MORDEDURA DE SERPIENTE. LA VISIÓN DEL INTENSIVISTA: REPORTE DE CASO

Andrés Alirio Restrepo Bastidas

1

1

Mateo Aguirre Flórez

1

1

Jaime Andrés Hoyos Muñoz

1

1

Melissa González Ramírez

1

1

David Ricardo Echeverry Piedrahita

1

1

1 Grupo Investigación de Medicina Crítica y Cuidados Intensivos GIMCCI. Universidad Tecnológica

de Pereira, Pereira, Risaralda, Colombia

ABSTRACT

Background: Ophidic accident is a neglected disease that affects tropical countries. Latin America is

the second region after Africa, with the most cases worldwide. Local lesions accompany its clinical

course up to systemic affectations such as renal, hematological, and neurological lesions. Cardiac

complications are rare, especially in patients who do not have cardiovascular risk factors. There are

reports of acute myocardial infarction, but there is little information about heart failure due to

Bothrops spp.

Case report: We present the case of a 25-year-old man without cardiovascular risk factors who was

admitted to the intensive care unit and developed heart failure with cardiogenic shock and multi-organ

failure secondary to a snake bite.

Conclusions: Although the characteristic clinical course of a bothropic ophidian accident and its

systemic manifestations are mainly related to coagulation abnormalities, there are cardiovascular

complications within its clinical presentation that, although rare, if not detected promptly and not

adequately managed, are associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Bothrops spp, cardiogenic shock, Colombia, heart failure, ophidic accident (Source:

MeSH).

RESUMEN

Antecedentes: El accidente ofídico es una enfermedad desatendida que afecta a los países

tropicales. América Latina es la segunda región después de África, con mayor número de casos a nivel

mundial. Su curso clínico incluye lesiones locales hasta afectaciones sistémicas como lesiones renales,

hematológicas y neurológicas. Las complicaciones cardiacas son raras, especialmente en pacientes que no

tienen factores de riesgo cardiovascular. Hay reportes de infarto agudo de miocardio, pero existe poca

información sobre la insuficiencia cardíaca debida a Bothrops spp.

Reporte de caso: Presentamos el caso de un hombre de 25 años sin factores de riesgo

cardiovascular que fue admitido en la unidad de cuidados intensivos y desarrolló insuficiencia cardíaca

con choque cardiogénico y fallo multiorgánico secundario a una mordedura de serpiente.

Conclusiones: Aunque el curso clínico característico de un accidente ofídico bothrópico y sus

manifestaciones sistémicas están principalmente relacionadas con anomalías de la coagulación, hay

complicaciones cardiovasculares dentro de su presentación clínica que, aunque raras, si no se detectan

prontamente y no se manejan adecuadamente, están asociadas con alta morbilidad y mortalidad.

Palabras clave: Bothrops spp, choque cardiogénico, Colombia, insuficiencia cardíaca, accidente

ofídico. (Fuente: MeSH).

INTRODUCTION

The existence of 3000 snake species has been estimated worldwide, of which 600 are poisonous and

threaten public health (1). Therefore, in 2019, the World Health

Organization (WHO) established the

venomous snake bite as a neglected tropical disease (2), with 5.4 million

cases reported each year, 95

000 fatalities, and 300 000 patients with some degree of disability (2). In

Latin America, 70 000 cases

per year are reported. Children, young agricultural workers and people from rural areas are among the

most affected (2 - 4).

Clinical findings range from local alterations such as erythema, pain, and bleeding (5) to systemic

complications like coagulopathies, necrosis, bacterial infections, nephropathies, and unusual

complications like myocardial infarction and arrhythmias (4, 6), reports of more systemic severe

alterations are rare (7). Heart failure secondary to bothropic accident is

infrequent; its origin is

multifactorial due to hypercoagulability, direct cardiotoxicity, vasospasm, hypoperfusion due to

hypovolemic shock and imbalance between procoagulant and anticoagulant elements; these factors can

generate acute myocardial injury with heart failure and cardiogenic shock, events that have a

significant impact on the prognosis of this pathology (16, 17,

18). Therefore, appropriate knowledge of

the treatment of venomous snake bites by medical staff is crucial to improving survival rates from this

condition (8). Consequently, the case of a 25-year-old male, without any

cardiovascular risk factors,

who was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to acute heart failure after being bitten by a

Bothrops spp snake is presented.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old male, afro-descendant, agricultural worker, resident of a rural area, without known past

diseases. He was admitted due to a Bothrops spp snake bite five hours earlier on the middle third of the

posterior region of the right lower limb. Two punctiform lesions with mild but active bleeding were

present. Edema, a diameter difference greater than four cm compared to the left lower limb, absent

distal pulses, and sensitivity alterations were also present. A local expert identified the genus of the

snake.

Laboratory tests showed prolongation of coagulation times (aPTT: 54.8 sec. – Reference Range: 29.2 sec.

PT: 47.7 sec. control: 12.9 sec. INR: 4.00), normal fibrinogen (>1200 mg/dL), creatinine phosphokinase

(CPK) (7261.0 U/L) -elevated. Therefore, according to the National Institute of Health (NIH), the case

was classified as severe, and the patient was treated according to the antivenom recommendations. In

addition, doppler ultrasonography of the right lower extremity arteries and veins was performed, which

showed signs of compartment syndrome (absence of color flows within the posterior tibial artery;

posterior and anterior tibial veins). Therefore, fasciotomy of the lateral and medial compartments of

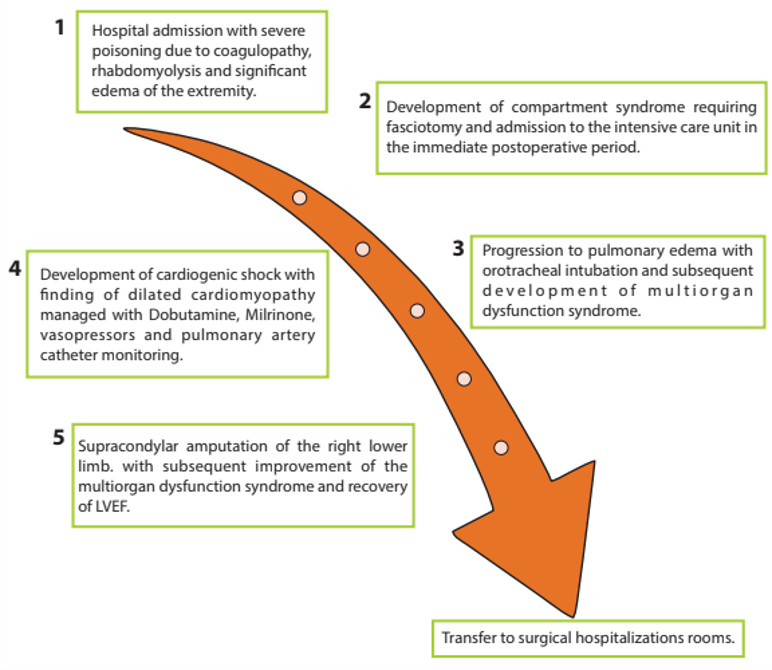

the leg from knee to ankle was required, and muscle necrosis was observed during the procedure (figure

1).

The patient was transferred to the ICU for postoperative care and required vasoactive support due to

hemodynamic instability. The patient also showed severe and progressive changes in tissue perfusion

parameters (SvcO2: 57 %, delta-pCO 2: 9, lactate: 9.9). An increase in vasoactive support dose and a

second vasoactive drug was necessary. A transthoracic echocardiogram shows dilated cardiomyopathy with

biventricular failure, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): 25 %; a tricuspid annular plane

systolic excursion (TAPSE) of 14 mm was performed. In addition, biomarker elevation (troponin I: 6.00

ng/ml - reference range: 0-0.120 ng/ml) indicated acute myocardial injury. Due to the echocardiographic

findings and clinical condition, inotropic support with dobutamine was implemented. The patient

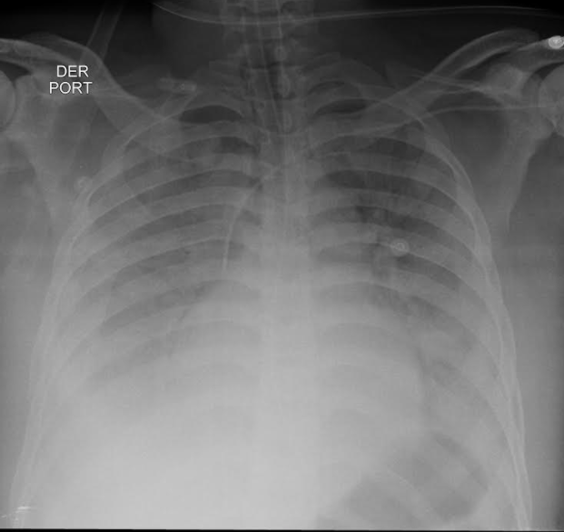

progressed to acute type 1 respiratory failure, and advanced airway management with invasive mechanical

ventilation was necessary (figure 2).

The patient presented dobutamine intolerance with persistent tachycardia (heart rate > 130 per minute), so a change to levosimendan (dose 0.1 μg/kg/min for 24 hours) was needed. However, hyperlactatemia persisted, and high doses of vasoactive drugs were required. Invasive hemodynamic monitoring via pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) showed a hemodynamic pattern of cardiogenic shock (table 1). The patient progressed to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome by cardiovascular (cardiogenic shock), pulmonary (pulmonary edema), renal (acute kidney injury), hematological (coagulopathy) and liver involvement (transaminase elevation). Due to the extension of muscle necrosis and the loss of limb viability, on the second day of hospitalization, a supracondylar amputation of the right inferior limb was carried out. A second inodilator was required (milrinone dose: 0.1 μg/kg/min). Afterward, the patient tolerated decreased vasoactive support and improved his tissue perfusion and kidney function indicators and reaching hemodynamic stability. On the fourth day of hospitalization, a control transthoracic echocardiogram showed LVEF recovery to 50 %. In the following days, the inodilator decreased, orotracheal extubation was carried out, and the patient was transferred to the general ward on the fifth day of hospitalization.

|

Hemodynamic variables |

Values |

Hemodynamic variables |

Values |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cardiac Index |

2.0 L/min/m2 |

BSA |

2024 m2 |

||||||||||||

|

SV |

46.5 mL |

SVI |

23.0 ml/m2 |

||||||||||||

|

SRV |

1259 Dinas/cm5 |

SRVI |

2549 Dinas*m2/cm5 |

||||||||||||

|

PVR |

120 Dinas/cm5 |

PVRI |

243 Dinas*m2/cm5 |

||||||||||||

|

LVSW |

48.1 g*m |

LVSWI |

23.8 g*m/m2 |

||||||||||||

|

RVSW |

12.65 g*m |

RVSWI |

6.25 g*m/m2 |

BSA: body surface area, SV: stroke volume, SVI: systolic volume index, SVR: systemic vascular resistance, SVRI: systemic vascular resistance index, PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance, PVRI: pulmonary vascular resistance index, LVSW: left ventricular systolic work, LVSWI: left ventricular systolic work index, RVSW: Right Ventricular Systolic Work, RVSWI: right ventricular systolic work index.

DISCUSSION

Snakebite poisoning, specifically by the Bothrops snake, can have several pathophysiological effects on

the body, what includes the risk of cardiogenic shock. Bothrops is a genus of venomous snakes found in

Central and South America (2, 3). Here, we describe some of

the basic pathophysiological mechanisms

related to the development of cardiogenic shock after a Bothrops bite:

Hemorrhagic toxins: Bothrops venom contains proteolytic enzymes and metalloproteinases that can

cause damage to blood vessels and surrounding tissues. This vascular damage leads to localized bleeding

and, in severe cases, a hemorrhagic syndrome that can affect multiple organs (4).

Compartment syndrome: Tissue breakdown and localized edema can increase pressure in the affected

muscle compartments. This increase in pressure can compromise local blood flow and contribute to shock

development (5).

Activation of the coagulation system: Bothrops venom can activate the coagulation system, which

can result in a cascade of events leading to the formation of clots and consumption of clotting factors.

This activation may contribute to microvascular thrombosis and tissue damage (6).

Hypotension: Blood loss due to the hemorrhagic action of the venom, and possible decreased

vascular resistance can lead to hypotension, a fundamental component of cardiogenic shock (6).

Myotoxicity: Some Bothrops species can have myotoxic effects, what causes direct damage to muscle

cells. The release of myoglobin and other damaged cellular products can contribute to acute renal

failure, further aggravating the patient's hemodynamic condition (7).

It is important to note that the clinical picture may vary, which dependss on the specific species of

Bothrops and the amount of venom inoculated. Immediate medical attention is crucial in venomous snake

bites to counteract the effects of the venom and prevent serious complications such as cardiogenic

shock. Depending on the patient's clinical manifestations, treatment may include antivenom

administration, hemodynamic support measures, and other specific therapeutic approaches (7, 8).

Venomous snake bite is a neglected tropical disease of great interest in public health (1, 2), and 5.4

million cases are reported yearly. It primarily affects tropical countries as Latin America, the second

most affected territory after Africa (9). Countries like Brazil report the

highest cases, approximately

26 000 ophidian accidents yearly (3). In Colombia, up to 4000 cases have

been reported (10), and it is

the second country in Latin America with the highest number of cases (3, 10). Young men who work as

farmers are the most affected (4, 9, 10),

and Bothrops spp is the most prevalent species and responsible

for 70 to 90 % of cases in the region (10 - 12).

Alterations caused by venomous snake bites are well known; local symptoms such as swelling, pain,

bleeding, edema, and muscle necrosis associated with systemic involvement (hematological and renal

mainly) are common (3, 4, (13)); on the other hand, different studies agree that cardiac

complications are

rare, especially among subjects without cardiovascular risk factors or known cardiac diseases (7). Four

possible mechanisms have been proposed for the development of acute myocardial infarction in both humans

and animals after an ophidian accident that generates heart failure: 1) vasospasm secondary to venom, 2)

coronary thrombosis due to hypercoagulability, 3) direct cardiotoxicity generating myocarditis and 4)

hypovolemic shock due to capillary leakage generation (16, 17). The venom of snakes of the Viperidae

family contains activators of factor V and factor X, which generate changes in the

procoagulant-anticoagulant balance. As a result, there is evidence of thrombosis of the coronary,

cerebral, and pulmonary vasculature (18). Generally, this type of event

does not lead to thrombosis in

humans since, in most cases, the venom injection is subcutaneous or intramuscular, leading to the

development of coagulopathy, preferably by consumption (19, 20), but in the case of this patient, due to

the large size of the snake, the volume of venom injected was very high with high penetration at

intravascular level, what increases the risk of thrombosis.

In this case, it was defined as an acute cardiac injury due to troponin elevation with values greater

than p99, associated with clinical and echocardiographic manifestations of myocardial ischemia, accord

to the fourth definition of myocardial infarction (17). Likewise, heart

failure was documented due to

the rapid progression of symptoms, a LVEF severely reduced, a Stevenson C hemodynamic profile, and signs

of tissue hypoperfusion, what indicates cardiogenic shock confirmed by invasive hemodynamic monitoring

with pulmonary artery catheter (18).

A study, performed in Brazil by Souza et al., identified risk factors for mortality in Brazilian

Amazonia. They found that Bothrops spp caused most cases, and fatal complications were respiratory

failure and kidney injury in 37 and 29.1 % of cases, respectively (12).

Only one patient with cardiac

involvement was identified. These data might be correlated with those obtained by Suresh et al. after

identifying the cause of death in a cohort of 533 patients in South India, where the most prevalent

cause of death was renal failure in 22.9 % of cases, and several cases of death, caused by cardiac

involvement, were reported (14).

Likewise, a study by Sarmiento et al., that comprised 42 patients, showed that the most frequent

complications were hematological and dermatological in 19.02 % of cases. However, it showed that three

patients had cardiac involvement and presents myocardial infarction (15).

Limitations and strengths

The clinical case has several limitations, among which we highlight that heart failure secondary to a

bothropic accident is a rare entity, so the literature available for its specific management is scarce,

without forgetting that patients admitted to the ICU due to a bothropic accident have high mortality; on

the other hand, in our context there is no availability of the adequate number of antidote vials, making

its management more difficult. The main strengths are related to the timely detection, advanced

hemodynamic monitoring, and management of heart failure with secondary cardiogenic shock, as well as the

different complications associated with the multi-organ dysfunction syndrome that the patient presented.

CONCLUSIONS

Although the characteristic clinical course of a bothropic ophidian accident and its systemic

manifestations are mainly related to coagulation abnormalities, there are cardiovascular complications

within its clinical presentation that, although rare, if not detected on time and not properly managed,

are associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Authorship contributions:

Andres Restrepo-Bastidas: Study concept and design, acquisition, analysis, and

interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content, original material, and construction of figures.

Mateo Aguirre-Flórez: Study concept and design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of

data. English translation.

Jaime Andrés Hoyos-Muñoz: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual

content and study supervision.

Melissa González-Ramírez: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual

content and study supervision.

David Echeverry-Piedrahita: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual

content and study supervision.

Financing:

Self-financed

Declaration of conflict of interest:

None of the authors declare conflicts of interest.

Recevied:

December 4, 2023

Approved:

February 29, 2024

Correspondence author:

Mateo Aguirre Flórez

Address:

Cra. 27 #10-02, Pereira, Risaralda, Colombia

E-mail:

maguirref96@utp.edu.co

Article published by the Journal of the faculty of Human Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University. It is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creatvie Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0/), that allows non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. For commercial use, please contact revista.medicina@urp.edu.pe.