LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2020 - Universidad Ricardo PalmaDOI 10.25176/RFMH.v20i3.2459

GEOGRAPHIC REGIONAL DISTRIBUTION OF PREVALENCE OF LOW BIRTH WEIGHT IN PERU

DISTRIBUCIÓN GEOGRÁFICA DE PREVALENCIAS REGIONALES DE BAJO PESO AL NACER EN PERÚ

Víctor A. Mamani-Urrutia1,2,a

1 Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima. Perú.

2Instituto Nacional de Salud Infantil, Lima. Perú.

a Bachelor of Human Nutrition, MSc.

Dear. Editor

Low birth weight (LBW) continuous to be a global public health problem and it is an important health indicator that identifies the social, economic, and environmental background of the newborn and his family,

determined when the birth weight is less than 2500 grams .(1-2) In Peru, this indicator is evaluated annually through the Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar (ENDES). The Ministry of Health

of Peru (MINSA) and the Registro Nacional de Identidad y Estado Civil (RENIEC) developed and began the implementation in 2012 of the Certificado de Nacido Vivo en Línea (CNV). This system allows the registration of newborns and generates a

real-time birth certificate, also records information such as gender, weight, height, characteristics of gestation and childbirth, among other nominal health variables, this system is free of charge and use by the public and private Health

Care Institutions (IPRESS).

(3)

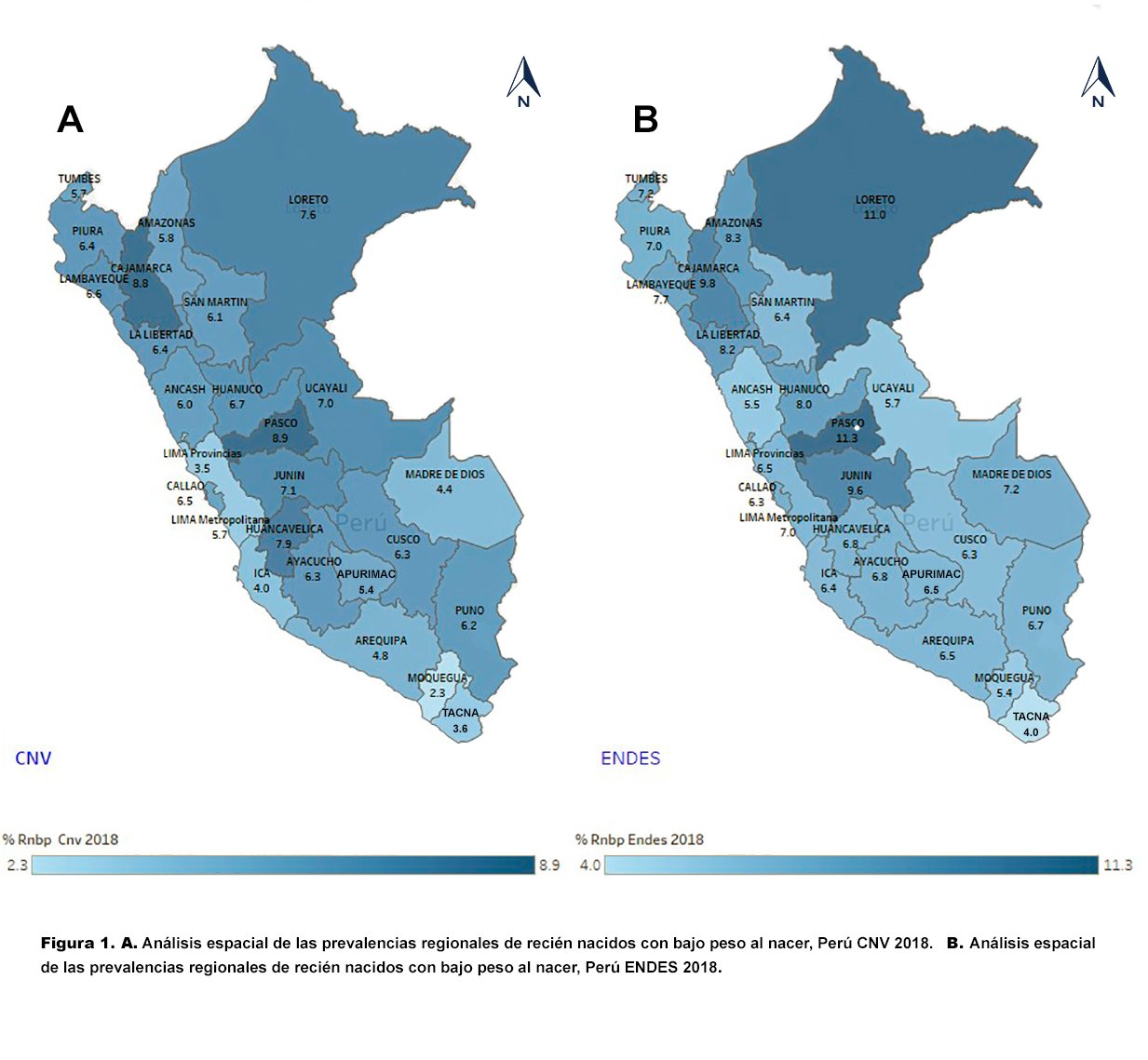

The objective of this communication is to show the spatial distribution of the regional prevalence in Peru of LBW reported by ENDES and CNV for the year 2018. An analysis was made of the information reported by the CNV, which originates

from the nominal register of health care in the IPRESS where births were attended by health personnel. The ENDES whose information is collected from health cards or information reported by the mother in the interviews conducted, although their

results are referential because of its high coefficient of variation has continuity in their reports for more than a decade. The existing statistical differences were compared with the prevalence reported by the ENDES and the CNV and categorization

were made into three groups according to the differences between the two sources of information.

We evaluated 494,024 records of newborns reported to the CNV for 2018 with full information to establish the prevalence of LBW and carry out the spatial distribution .(4) We observed a difference in the

national prevalence of LBW of 1.3% in comparison with the ENDES of the same year, at the regional level we have that the group with the greatest difference (between 2.4% to 3.4%) were found Ica, Pasco, Amazonas, Junín, Madre de Dios, Lima

Provinces, Moquegua and Loreto. The group with a different intermediate (between 1.3% to 1.8%) are Huánuco, Lima, Ucayali, Tumbes, Arequipa, and La Libertad. Finally, the group with a different minimum (between 0% to 1.1%) are located in Cusco,

Callao, San Martín, Tacna, Ancash, Ayacucho, Puno, Piura, Cajamarca, Apurimac, Huancavelica, and Lambayeque. The differences found to show that all cases were less than ±3.5% between CNV and ENDES (Figure 1), all reported values agree with

global estimates (14.6%) and for Latin America and the Caribbean (8.7%) (1), It evidences the importance of having nominated health information systems that allow accurate population health interventions .(5)

The CNV has been closing coverage gaps, according to the projection of births of the Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI), the CNV had 12.4% coverage among registered births for the year 2012, with an increasing trend

over time and achieving 88.1% coverage for the year 2018 (4), The CNV has been closing coverage gaps, according to the projection of births of the Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI), the CNV

had 12.4% coverage among registered births for the year 2012, with an increasing trend over time and achieving 88.1% coverage for the year 2018 (6). The difference highlights the ENDES that only gives us reference

information at the regional level for the indicator of LBW (7), e), the system CNV allows us to count with nominal data to track each child and allows that the Integrated Health Network Addresses (DIRIS) at the

national level to coordinate health interventions with their regional and local authorities, the MINSA should continue to strengthen the systems of nominated information being implemented at the national level.(6,8)

En conclusión, el 6.0%(4)of newborns reported by the CNV have LBW compared to 7.3% (6) qreported by ENDES for 2018, 12 of the 26 spatial distribution have a difference of less

than 1.1% between both sources of information. The CNV provides nominated information for follow-up interventions at the population level and to help improve the health of mothers and newborns.

Contributions: The author has participated in the conception of the manuscript, collection of the data, interpretation of the data, and approval of the final version of the manuscript. Financing: self-financed .

Financing: self-financed.

Declaration of conflicts of interest: The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest in the publication of this article.

Agradecimiento: El autor agradece la valiosa colaboración del Lic. Aldo Balta y el Sr. John Moscoso en la edición y diagramación de los mapas presentados.

Received:November 08, 2019

Approved:May 19, 2020

Correspondence: Víctor Alfonso Mamani Urrutia, Universidad Científica del Sur. Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud. Carrera de Nutrición y Dietética.

Address: Panamericana Sur Km 19, Villa, Lima. Perú.

Telephone number: (511) 993 078 393.

Email: vmamaniu@gmail.com

REFERENCES