CLINICAL CASE

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2020 - Universidad Ricardo PalmaDOI 10.25176/RFMH.v20i3.3002

ACUTE APPENDICITIS IN PREGNANT WOMEN: A CASE REPORT

APENDICITIS AGUDA EN GESTANTE: UN REPORTE DE CASO

A. Cvetkovic-Vega1,a, Wendy Nieto-Gutierrez2,a

1 Universidad Continental, Lima-Perú.

2Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Lima-Perú..

aMedical surgeon

Acute appendicitis is the most common pathology from acute abdomen during pregnancy, which has a difficult diagnosis because of the physiological changes during pregnancy which results in confusing clinical presentations. We reported the case of a multiparous woman of 27 years with 22 3/7 weeks diagnosed with acute appendicitis, undergoing surgery without complications and with a necrosed appendix that was evidenced through pathological examination. It is important to emphasis the role of the anamnesis with the physical examination guided by the physiological pregnancy changes related to the appendix. A timely diagnosis and treatment with an interdisciplinary approach would significantly reduce the maternal-fetal risks related to this pathology, the appendix removal and the continuation of the pregnancy.

Key words: Appendicits; Pregnancy; Acute abdomen (source: MeSH NLM)

RESUMEN

La apendicitis aguda es una patología de abdomen agudo quirúrgico frecuente en el embarazo, siendo de difícil diagnóstico debido a los cambios fisiológicos del embarazo que ocasionan cuadros clínicos confusos. Reportamos el caso de una gran multigesta de 27 años de 22 semanas 3/7 en el cual se diagnosticó clínicamente apendicitis aguda, siendo intervenida quirúrgicamente sin complicaciones, encontrándose un apéndice necrosado corroborado posteriormente con anatomía patológica. Es importante enfatizar el rol de la anamnesis dirigida aunado al examen clínico orientado por los cambios fisiológicos del embarazo. Un diagnóstico oportuno junto al manejo interdisciplinario permitirá reducir significativamente los riesgos materno y fetales relacionados a esta patología, y tanto la extirpación del apéndice como la continuación del embarazo.

Palabras Clave: Apendicitis; Embarazo; Abdomen agudo (fuente: DeCS BIREME)

Close to 2% of pregnant women require surgery for some non-obstetric cause, of which surgical acute abdomen is the most frequent(1),with an incidence during pregnancy of 1 per every 500-635 pregnant women (2), with appendicectomy(44%) and cholecystectomy (22,3%) among the most frequent non-obstetric surgeries performed (1). Acute appendicitis has a prevalence of 1 out of every 1500 pregnant women (2), presenting more frequently during the second trimester of pregnancy(3)and in nulliparous women(4). Studies, such as Anderson(5) exist which suggest that pregnancy reduces the incidence of acute appendicitis, especially during the third trimester. This affirmation was studied in 2020 by Moltubak et al. who reported, from a group of Swedish pregnant women, a tendency in the incidence standardized rate for non-perforated appendicitis in pregnant women, with a variation from 1,09 (IC: 1,03-1,15) in the first trimester, 0,98 (IC: 0,93-1,04) in the second and finally 0,37 (IC: 0,33-0,41) in the third(6).

According to Zingone et al, pregnant women have les probability of being diagnosed with acute appendicitis than non-pregnant women(7). This fact is correlated with the delay in diagnosis and onset of treatment (8), which explains the reports of higher rates of appendicular perforation in pregnant women (2,3). Despite the classic appendicular pain location in the right inferior quadrant and that some studies report that there is no variation in such a presentation(8), it is important to consider the physiological changes in pregnancy that may cause a modification in the position of the appendix, which makes it more evident after the 24th week in locations above the right iliac crest, and able to be located close to the gallbladder at the end of pregnancy(9). Aside from pain, other symptoms may occur such as nausea and pain on decompression.

In laboratory findings, left shift leukocytosis, microscopic hematuria, leukocyturia, mild elevation of bilirubin, and C-reactive protein may be present(3). All these findings together with a semiological exploration can lead to the surgeon postponing the emergency surgery as a main diagnosis and assume other pathologies such as pyelonephritis, threatened miscarriage, renal colic, tubo-ovarian abscess, acute cholecystitis, pelvic inflammation, ectopic pregnancy, premature rupture of membranes, acute pancreatitis, among others(10).

Pregnant women with acute appendicitis have a risk of 2.68 times more of preterm labor and placental abruption, in addition with 1.3 times risk of peritonitis (12). This shows that the delay in an accurate diagnosis of acute appendicitis in pregnant women puts the mother’s life at risk and consequently the fetus’ life. Given the above, we present the current case below.

CASE REPORT

Female patient of 27 years of age with obstetric history of 6 pregnancies, occupation housewife, from Ayacucho, residing in Lima. Referred by a health post with the diagnosis of a threatened miscarriage and presenting, as of one day, colicky periumbilical abdominal pain with 5/10 intensity, not radiating. She arrives at the gynecological emergency where she is examined and diagnosed with a threatened miscarriage and urinary tract infection (UTI) and is admitted. However, in a matter of three hours, the abdominal pain becomes diffuse and increasing intensity to 8/10, associated with hyporexia, nausea, and two episodes of vomiting food and feeling feverish. She denied headache, vaginal bleeding, or loss of amniotic fluid. In her medical history she has six pregnancies, four live children born full-term by eutocic delivery and two abortions that were intervened through manual intrauterine aspiration in 2005 and 2015. She denies hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis, HIV or history of tuberculosis.

Upon physical exam we find the abdomen globular and painful on deep palpation at the right and left iliac fossae, hypogastrium and epigastrium. We found pain over Mc Burney’s point, positive Blumberg sign and absent lumbar closed fist percussion. Traces of white non-odorous vaginal discharge was found in labia majora, with a fundal height of 14cm. Her vital signs were registered, reporting a blood pressure of 100/58 mmHg, heart rate 88 beats/minute, respiratory rate of 18 per minute and temperature of 37.8°C. The following auxiliary tests were registered: Blood count with leukocytes (13,35 000/mm3), segmented 89.8%, banded 0%, hematocrit 31.1%. Urine test with leukocytes 50 - 70 x field, red blood cells 15 - 18 x field, ketone positive 1+, nitrites negative. Blood urea y creatinine at 12mg/dl and 0.56g/dl, respectively. Additionally, a fetal ultrasound was performed with compatible findings of an active singleton pregnancy of 22 weeks and 3 days through fetal biometry and preserved fetal well-being.

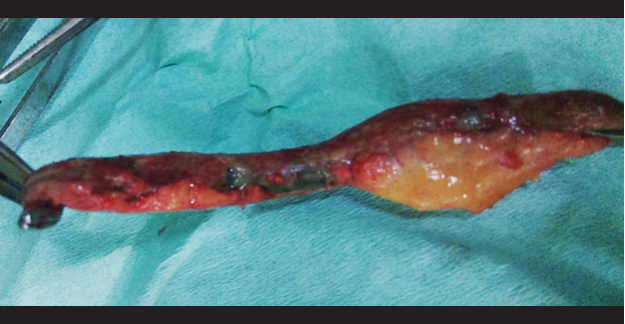

After this evaluation, the following diagnoses are presented: 1) Multiparous woman of 22 weeks and 3/7 by 2nd trimester ultrasound, 2) Acute abdomen requiring surgery, rule out acute appendicitis and 3) Urinary tract infection: vulvovaginitis. An anterograde appendectomy with free residual stump was performed with spinal anesthesia performing a transverse incision from the right iliac fossa towards the cavity, finding a cecal appendix in high left paracecal position of 10 x 1 cm diameter, necrotic walls in 2/3 ends, base in good condition and 15 cc of inflammatory liquid. There were no intraoperative complications. The diagnosis was confirmed through pathological anatomy, initiating treatment with ceftriaxone for 4 days, and after 5 days, by order of the Gynecology department, an obstetric ultrasound was performed with confirmation of an active singleton pregnancy of 23 weeks through fetal biometry and preserved fetal well-being. Patient follow-up showed no complications and she gave birth to a healthy baby girl at 40 weeks.

DISCUSSION

Acute appendicitis represents 44% of all non-obstetric causes that require surgery during pregnancy (1). Studies show that they have a higher presentation rate during the second trimester of pregnancy(4), which correlates with what was presented in this case. The clinical presentation of acute appendicitis is affected by physiological changes in pregnancy, increasing pain and generalized abdominal sensitivity(3,8 ), and modifying the position of the appendix(9),all of which decreases the efficacy of the clinical location of pain and the associated intensity. Even the general symptoms in appendicitis such as nausea, vomiting and hyperthermia tend to be findings that can be attributed to specific stages in pregnancy (2).For these reasons, the classic scene that we are facing may not be the same due to distractors that could lead to consider postponing surgical considerations, which would delay an adequate intervention and probably increase maternal-fetal mortality(4,13,14). We must remember that fetal mortality is accompanied by appendicular perforation rates of 20 to 35 % increasing to 66% if its diagnosis is delayed for over 24 hours(2).

It is important to consider the anamnesis and detailed semiological exam allowing to consider it as a surgical case during hospitalization. As a reminder, the patient was initially admitted for a threatened miscarriage and UTI. This situation serves as a reflection when there is a delayed initial diagnosis, which corresponds to the findings that pregnant women with appendicitis undergo non-surgical treatment more than those not pregnant(15). It is imperative when facing situations as the presented case, we consider acute appendicitis among the differential diagnoses, considering of course, the possibility of an emergency surgical intervention. With relation to diagnostic imaging, the literature recommends the use of ultrasound when facing a suspected appendicitis diagnosis(1), keeping in mind its diagnosis sensitivity of 83.7% and specificity of 95.9%(16).Due to its safety and efficacy, its precision is better at an earlier gestational age, especially before 16 weeks and less after 32 weeks(2).However, this could have limitations in obese patients and, due to the presence of intestinal gas, we even recommend magnetic resonance imaging in these cases.

Surgery is the treatment of choice when facing an acute appendicitis, a safe indication, especially during the second trimester, since the organogenesis is complete and pre-term labor is less than 1 % (13).Besides, it is important to recommend minimal uterine traction and manipulation during surgery, despite there not existing an association between manipulation and prematurity(3).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the possibility of acute appendicitis in pregnant women invites us to consider scenarios with presentations disguised by pregnancy conditions and that would only delay beginning surgical intervention. We recommend prioritizing the anamnesis and thorough physical exam combined with laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging such as ultrasound, if deemed necessary. The timely diagnostic confirmation and prompt intervention will lower the maternal and fetal morbimortality, allowing the continuation of the pregnancy once the clinical presentation is overcome.

Acknowledgements:To Lic. Andrea Chuquitaype, part of the teamwork.

Author declaration: ACV performed the work development and design, data collection, results analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting and critical review, approval of final version, patient input and financing. WNG performed

the result analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting and critical review and approval of the final version.

Source of financing: ASelf-financed.

Declaration of conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Received: May 31, 2020

Approved: June 14, 2020

Correspondence: Aleksandar Cvetkovic Vega.

Adress: Jr. Bronsino 307, San Borja, Lima-Perú.

phone number : +51 964982676

E-mail: acvetkovic@continental.edu.pe

BIBLIOGRAPHY