ARTICULO ORIGINAL

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2021 - Universidad Ricardo Palma10.25176/RFMH.v21i2.3621

PATELLAR LIGAMENT RUPTURE AS A COMPLICATION OF POOR APPLICATION TECHNIQUE OF RADIAL PRESSURE WAVE THERAPY. REPORT OF TWO CASES:

ROTURA DE TENDONES ROTULIANOS COMO COMPLICACIÓN DE MALA TÉCNICA DE APLICACIÓN DE ONDAS DE PRESIÓN RADIAL. REPORTE DE DOS CASOS:

Walter Insuasti Abarca(2)Paul Terán Vela(1), Sussan Llocclla Delgado(3), Tania Platero-Portillo(4), Diana Martínez Asnalema(5), Lilian Abarca García(6)

1 Medical Doctor. Orthopedic Surgeon, Centro de Especialidades Ortopédicas, Quito – Ecuador.

2 Medical Doctor. Department of Internal Medicine, Centro de Especialidades Ortopédicas, Quito –

Ecuador.

3 Medical Doctor. Biomedical Sciences Research Institute. Universidad Ricardo Palma, Santiago de

Surco – Perú.

4 Medical Doctor. School of Medicine, Universidad de El Salvador, San Salvador – El Salvador.

5 Medical Doctor. Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Hospital General Luis

Dávila, Tulcán – Ecuador

6 Medical student. School of Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito –

Ecuador.

ABSTRACT

Patellar tendinopathy is characterized by anterior knee pain located at the lower pole of the patella at the junction of the patellar tendon. This is often a disabling condition that limits patients' quality of life, affects their ability to participate in sports, and even hinders their normal daily activities. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has been recognized as a promising and safe alternative for the treatment of various musculoskeletal disorders – including chronic patellar tendinopathy. However, there is limited evidence regarding its side effects, in particular ESWT-associated tendon injuries. To the authors' knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating clinical and radiological evidence of two patients without known risk factors for partial patellar tendon tears that developed this condition after the application of radial pressure wave therapy - also known as radial shock wave therapy - for patellar tendinopathy. ESWT must be applied by properly trained professionals so that specific requirements needed to guarantee an appropriate application technique, minimize possible adverse effects, and improve patient safety could be met.

Keywords: Patellar ligament; Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy; Tendinopathy; Case reports. SOURCE : Mesh - NLM

RESUMEN

La tendinopatía rotuliana se caracteriza por dolor anterior de la rodilla localizado en el polo inferior de la rótula en la unión del tendón rotuliano. Esta es, a menudo, una condición discapacitante que limita la calidad de vida de los pacientes, afecta su capacidad para participar en deportes e incluso dificulta sus actividades cotidianas. El tratamiento de ondas de choque extracorpóreas (ESWT por sus siglas en inglés) ha sido reconocido como una alternativa prometedora y segura para el tratamiento de diversos trastornos musculoesqueléticos, incluida la tendinopatía rotuliana crónica. Sin embargo, existe evidencia limitada con respecto a sus efectos secundarios, en particular las lesiones de tendones asociadas con ESWT. Según el conocimiento de los autores, este es el primer artículo que demuestra evidencia clínica y radiológica de dos pacientes sin factores de riesgo que presentan desgarros parciales del tendón rotuliano después de haber recibido terapia de ondas de presión radiales, también conocida como terapia de ondas de choque radiales, como tratamiento para la tendinopatía rotuliana. El tratamiento con ondas de choque debe ser aplicada por profesionales debidamente capacitados para que se cumplan los requisitos específicos necesarios para garantizar una técnica de aplicación adecuada, minimizar los posibles efectos adversos y mejorar la seguridad del paciente.

Palabras Clave: Ligamento rotuliano; Tratamiento con Ondas de Choque Extracorpóreas; Tendinopatía; Informes de Casos. Fuente: Decs - BIREME

INTRODUCTION

Patellar tendinopathy, also called "jumper's knee" (1), is

characterized by anterior knee pain located at the lower pole of the patella at the junction of the

patellar tendon. This condition is common among athletes who perform jumping activities with a

prevalence of around 36% in basketball and volleyball players (2). More often,

patellar tendinopathy is related to injuries produced after repetitive mechanical tension of the

patellar tendon producing an inflammatory response with subsequent tendon fiber degeneration. It can

limit patients' quality of life, affect their ability to participate in sports, and even hinder their

normal daily activities.

On the other hand, patellar ligament rupture is a very rare disorder with an estimated

prevalence of 0.6% . Risk factors that may predispose patients to develop this condition include

obesity, being high elite or amateur athletes with chronic patellar tendinopathy (generating repetitive

microtraumas over the tendon) (3), systemic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid

arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus), long-term corticosteroid use, chronic kidney disease,

fluoroquinolone use (4), elderly, and previous surgical procedures that

disturb the midsubstance or insertion sites of the patellar tendon, such as total knee arthroplasty

(5).

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has been recognized as a promising and safe alternative

for the treatment of various musculoskeletal disorders – including chronic patellar tendinopathy

(6) - due to its practical analgesic effects and ability to promote tissue

remodelling and repair (6-7).

Currently, there are several shock wave therapy application devices, and each unit varies in

terms of the type of wave it provides - radial or focal - thus determining its use for a specific

pathology; however, the energy provided by the devices is given primarily on an operator basis, so the

risks of applying shock waves do not depend on the device used, but on the protocol established by the

operator.

There are currently two wave types, first, a focal shock wave that provides a more significant

amount of energy in deep planes generated by piezoelectric, electromagnetic, or electrohydraulic

equipment that can activate reparative cellular processes even in bone tissue. Second, a radial pressure

wave that is generated through the kinetic transmission of energy on an applicator and has a more

superficial effect on the tissues. (8)

The Latin American Societies and Associations on Shockwave in Medicine (ONLAT) (9) has made efforts to define the risk factors linked to complications after

shock wave therapy application. These include:

- Diagnostic errors. Prior to the administration of shock wave therapy, the type of pathology must be correctly identified - e.g. tendinopathy; calcific or fibrous tendinopathy; tendon tear; unspecific pain syndrome.

- Technical errors generated by the operator. The operator must be qualified and trained by the corresponding scientific societies. In addition, the anatomy, physiology and pathophysiology of the disease being treated, as well as the indications and contraindications of the therapy, must be completely understood. Lack of knowledge about the type of device and its characteristics is also classified as a technical error. Knowing the correct application technique of shock wave therapy is mandatory, e.g. correct position of the patient during the procedure, localization of the site to be treated -which is generally identified under ultrasonographic guidance-, and establishment of the ideal energy protocol for each pathology.

- Adverse effects of the radial wave therapy application such as increased pain, erythema, bruising, among others. Adverse effect management should be addressed by the medical personnel.

There is limited evidence regarding the side effects of the therapy, in particular ESWT-associated tendon injuries. In fact, there is only one case in the literature reporting an Achilles tendon rupture after ESWT (10); consequently, to the authors' knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating two cases of partial patellar tendon tears after the application of radial pressure wave therapy also known as radial shock wave therapy.

PRESENTATION OF CASES:

CASE 1:

A 16-year-old previously healthy boy arrived at Centro de Especialidades Ortopédicas in Quito

complaining about intense right knee pain. The pain started insidiously three months before when the

patient started practicing basketball at his high school. Initially, the patient was evaluated in

another medical facility where he was prescribed seven radial pressure wave therapy sessions at a

one-week interval with an energy of 5 Bar and a high frequency of 15 to 20 Hz using a BTL-5000 SWT POWER

equipment, and no anesthesia was administered. Ultrasonography performed before the therapy demonstrated

complete tendon fiber integrity. (Figura 1).

According to the patient, the first radial pressure wave therapy session abruptly increased his

knee pain, making him unable to continue walking. As a result, no more ESWT were administered, and one

week later he received an intra-articular injection of 80 mg of methylprednisolone without sonographic

guidance that failed to improve his pain. He then underwent a complete right knee joint immobilization

followed by several physical therapy sessions without improving his symptoms.

Six weeks after receiving the intra-articular corticosteroid injection, the patient was referred

to our clinic, where physical examination revealed diffuse swelling on the right anterior knee,

significant pain and tenderness over the patellar tendon (9/10 in the Visual Analogue Scale), difficulty

on leg extension, and a decreased range of motion. Positive Zohler's and Clarke's tests were present,

representing concomitant signs of grade I patellar chondromalacia. The Victorian Institute of Sports

Assessment (VISA-P) score for patellar tendinopathy was 38/100, and the patient's Blazina Scale was

IIIb.

Blazina Scale (11) classifies the disease based on five stages which

determine the severity of the injury through symptoms that occur at different levels of sport or

activity.

Table 1. Blazina Scale

| Classification | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | No pain |

| Stage I | Pain after intense sports activity |

| Stage II | Pain at the beginning and after sports activity |

| Stage III | Phase III a: Pain during and after activity, but allows regular

workouts Phase III b: Pain during and after activity, but unable to perform regular workouts |

| Stage IV | Pain during sporting activity unable to participate in sports to a satisfactory level |

| Stage V | Pain during daily activity. Unable to participate in any sport level |

The VISA-P scale (12) can be applied to quantify symptoms, function, and the

ability to perform sports activities in the context to patellar tendinopathy. In addition, it can be

used to monitor the recovery of patellar tendinopathy because it allows an early detection of worsening

symptoms. The VISA-P questionnaire consists of 8 items with a score from 0 to 100, and 100 is considered

a satisfactory result.

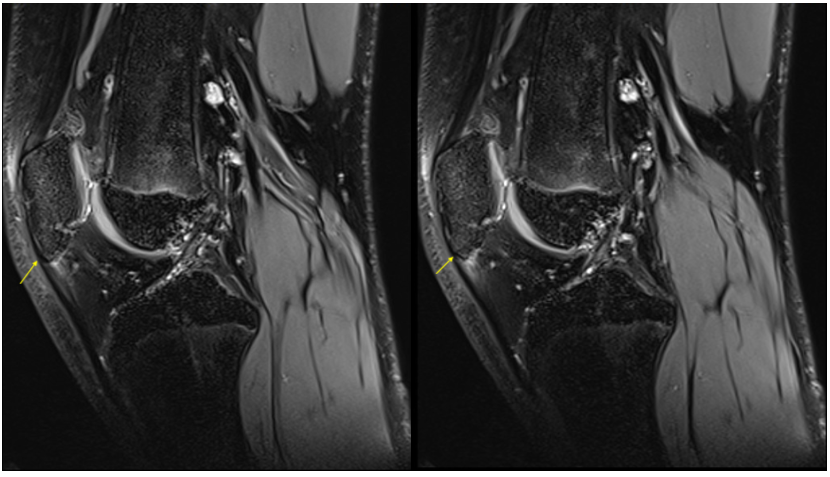

Magnetic resonance imaging of the right knee performed at our clinic revealed a partial patellar

tendon tear of 3.8 mm, as well as thickening and edema of its superior portion (Figure

2 ). In addition,

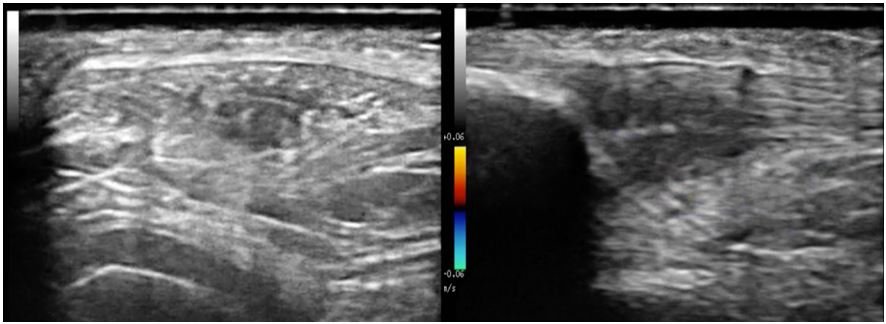

ultrasound elastography demonstrated an intrasubstance patellar tendon tear of 4 mm and calcification of

its deep portion with a stiffness value of 5 kPa., whereas the resting normal tendinous fibers

demonstrated a stiffness value of 1.2 kPa. (Figure 3 ).

Conservative management was decided considering the patient's age. First, the administration of

two 4ml intratendinous injections of PRO-PRP KIT leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma using

interventional ultrasound was performed. This was followed by several physical therapy sessions, and

administration of two low-energy sessions of focal extracorporeal shock wave therapy (fESWT) at a

one-week interval. Weeks after treatment, we documented a complete tendon healing by performing serial

ultrasound examinations. The pain almost resolved (1/10 in the Visual Analogue Scale), and his VISA-P

score was 88/100, so the patient was able to return to normal activities.

It is important to mention that we decided to apply treatments other than physical therapy,

medication, and rest, because this patient had previously been treated with various conservative

therapeutic measures that did not show favorable results. In addition, it was also decided to apply

these "unconventional" treatments due to the large amount of fibrosis and calcification that the patient

presented in the tendon insertion area for which both PRP and the use of focal shock waves have shown

benefits. On the other hand, it is necessary to emphasize that this patient’s age absolutely

contraindicated the use of high intensity laser due to the ray´s depth of penetration which can affect

the patient’s growth plate.

CASE 2:

A 25-year-old previously healthy man arrived at Centro de Especialidades Ortopédicas in Quito

complaining about intense right knee pain that started insidiously several months ago after starting

playing soccer on weekends. Initially, he sought medical attention in another medical facility where

twenty radial pressure wave therapy sessions on the right knee were prescribed at a one-day interval

with an energy of 4 Bar and a frequency of 10 to 15 Hz using a BTL-6000 SWT EASY equipment, and no

anesthesia was administered. Ultrasonography performed before the therapy demonstrated proximal patellar

tendon thickness and edema, as well as complete tendon fiber integrity with no signs of peritendinous

vascularization. (Figure 4).

After the fifth shockwave therapy session, the patient denoted significant pain increase over

the application area, and over the next few days, he was unable to walk or climb stairs, so he decided

not to continue receiving the therapy and looked for a second evaluation at our clinic.

The patient's physical examination at our clinic showed a positive Bassett sign and an extremely

painful right knee extension (9/10 in the Visual Analogue Scale). Furthermore, edema and ecchymosis were

noticed over the patellar region of the right leg. The Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment (VISA-P)

score for patellar tendinopathy was 37/100, and the patient's Blazina Scale was IIIb.

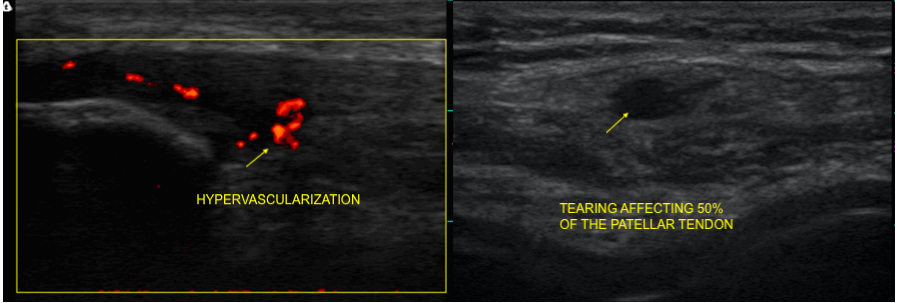

We performed an ultrasound that evidenced a right partial patellar tendon tear compromising

approximately 50% of its whole depth surrounded by multiple blood vessels. (Figure

5).

Using interventional ultrasound, we administered 4 intratendinous and 10 peritendinous ml of

PRO-PRP KIT leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma. Afterward, the patient was advised to use crutches for

two weeks followed by administration of ten continuous-mode 5.00-W-power high-intensity laser (HIL)

therapy sessions at one-day intervals over the right patellar tendon using a BTL- high intensity laser-

12W equipment.

Finally, twenty physical therapy sessions were prescribed at one-day intervals. The sessions

were focused on stretching of the lower extremity musculature, friction massage of the patellar tendon,

eccentric quadriceps exercises, and strengthening the hip and knee musculature. The patient achieved a

complete tissue and functional recovery, and three months after treatment, his VISA-P score was 91/100.

|

DISCUSSION

Multiple evidence supports the use of extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) as effective and safe in

treating patellar tendinopathy. Liao et al., (13) in a recent meta-analysis

of randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of extracorporeal shock wave therapy for knee

tendinopathies and other soft tissue disorders, concluded that ESWT exerts a positive effect on the

treatment success rate, pain reduction, and range of motion restoration in patients with knee soft

tissue disorders. Similarly, Van Leeuwen et al., (7) in a review of the

literature involving seven studies in which more than two hundred patients with patellar tendinopathy

were treated with ESWT, concluded that this treatment seems to be a safe and promising alternative for

this tendinopathy with a positive effect on pain and function. Lastly, Wang et al., (14), in a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of

extracorporeal shockwave therapy compared to conservative treatment for chronic patellar tendinopathy,

found positive outcomes in 90% of patients in the study group compared to only 50% of patients in the

control group. Furthermore, recurrence of symptoms occurred in only 13% of patients in the study group

and 50% in the control group.

Concerning the side effects of the therapy, even though Furia et al., have reported some mild

side effects as a consequence of ESWT such as ecchymosis, petechiae, slight swelling, and temporary

reddening of the skin (15), there are very few reports in the literature

demonstrating severe complications like the ones seen in our patients.

At date, there is only one previous study reporting a tendon rupture after ESWT (10). In this case, a female patient with a history of chronic calcific

Achilles tendinopathy experienced Achilles tendon rupture two months after being treated with ESWT. The

study concluded that despite ESWT is generally considered safe, physicians should be aware of

potentially significant complications such as tendon tears.

It is worth mentioning that none of our patients had any of those risk factors. They also had

pre-therapy patellar tendon ultrasonography that demonstrated complete tendon fiber integrity; hence, we

can only conclude that their patellar tendon ruptures were produced as iatrogenic consequences of poor

application technique of radial pressure wave therapy.

Even though the patients’ histories differ from the ones who develop patellar tendinopathy, it

is worth mentioning that the patients’ symptoms started to develop right after a sudden increase in

their physical activities - they started to practice a new sport -. This precipitated change in physical

activity may have contributed to the development of patellar tendinopathy. In this context, it is well

established that progressing physical loading, high intensity training, or repetitive loading too fast

may contribute to the development of this condition. (16). In addition, it is

possible that an interaction between various intrinsic and extrinsic factors with the genetic make up of

our patients could have increased their likelihood to develop tendinopathy. (17).

Another aspect to consider is that in the first case the patient’s age made the diagnosis of

patellar tendinopathy less feasible; however, complementary exams like plain radiographs, MRI and

ultrasonography failed to confirm other causes of patellar tendon pain, e.g. Sinding Larsen Johansson

Syndrome.

Even though there is enough evidence supporting the use of ESWT for the treatment of patellar

tendinopathy, we have identified health providers' lack of expertise as a major risk factor for ESWT

side effects (18). As mentioned previously, risk factors may play an

essential role in developing patellar tendon rupture, but several studies suggest that this condition is

often the result of direct trauma over the tendon among healthy individuals such as our patients

(3). When radial pressure wave therapy is used, tendinopathies are treated

with an energy between 4 and 5 Bar, and a low frequency ranging from 6 to 10 Hz. (6) at a one-week interval. However, in the first case, in addition to

inappropriately using a high frequency of 15 to 20 Hz., the patient’s age made the use of radial

pressure wave therapy contraindicated. Likewise, in the second case, the therapy was applied erroneously

at one-day intervals. In regard to this matter, Leal et al., (6) in a review

about the use of extracorporeal shock wave therapy for chronic patellar tendinopathy, suggest a maximum

of five sessions should be applied for the treatment of this tendinopathy when radial pressure wave

therapy is used; thus, in both cases, the protocols were breached.

It is worth mentioning a brief description of the treatments we used in order to help achieve a

complete tissue and functional recovery in our patients.

In the first case, we administered two low-energy sessions -0,10mJ/mm2- of focal extracorporeal

shock wave therapy (fESWT) at a one-week interval. The use of fESWT is well recognized for providing

high-quality energy over tissues leading to activation of reparative cellular processes; thus, promoting

tissue repair and neovascularization (6-8). In addition, there is far more

evidence recommending the use of fESWT to treat patellar tendinopathy compared to radial shock wave

therapy (6-8-14). This means that even though an inappropriate shock wave therapy application protocol

can lead to severe adverse effects as the ones observed in our patients, the appropriate use of ESWT can

definitely lead to positive outcomes.

Regarding the use of poor leukocyte platelet rich plasma, there is a lot of emerging evidence

supporting its effectiveness in patellar tendinopathy. Many studies suggest that it promotes tendon

healing through the delivery of platelet-derived growth factors and bioactive molecules in

hyperphysiologic doses that enhance tissue repair mechanisms. (19). In

addition, studies which investigated the effects of PRP in vitro and in vivo, demonstrated benefits that

include improved cellular remodeling and decreased healing time (20).

Finally, in the second case, we administered ten continuous-mode 5.00-W-power high-intensity

laser (HIL) therapy sessions at one-day intervals. There is evidence supporting HIL effectiveness in

inhibiting pain pathways in the nervous system as well as the production of anti-inflammatory effects by

locally stimulating blood and lymph circulation, which leads to reduced edema and increased blood

supply. Both effects are produced by the generation of heat in the diseased tissue - an increase of

approx. 2°C–3°C- and the mechanical stimulation of nociceptors and other nerve terminals (21-22). Consequently, HIL has emerged as a reliable, safe, and effective

treatment option in the treatment of various musculoskeletal conditions (23).

The main limitation of our report is its retrospective nature. Since the patients received

radial shock wave therapy in other medical centers, we were unable to collect valuable information

regarding the number of shocks used, or the precise site of radial pressure wave therapy application.

CONCLUSION

This report demonstrates the potentially harmful effects of radial pressure wave therapy for patellar

tendinopathy in two otherwise healthy individuals. As stated earlier, none of our patients had risk

factors that could have compromised their patellar tendon integrity; therefore, traumatic partial

patellar tendon ruptures following a poor application technique of radial shockwave therapy are the most

consistent diagnosis.

It is important to mention that we were able to evaluate the patients relatively shortly after

they developed their patellar tendon tears, so we could appropriately confirm the diagnosis clinically

and radiologically.

As we detailed in a previous report, ESWT must be applied by professionals certified by the

International Society for Medical Shockwave Treatment (ISMST) or by the Latin American Societies and

Associations on Shockwave in Medicine (ONLAT). Therefore, specific requirements needed to guarantee an

appropriate application technique, minimize possible adverse effects, and improve patient safety could

be met.

More research is required to clarify the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in tissue injury

after ESWT.

More research is required to clarify the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in tissue injury

after treatment with radial pressure waves when there is application technique failure.

It is essential to follow the recommendations that the scientific evidence provides in order to

establish appropriate treatment protocols for each particular patient. When focal shock wave therapy is

used for the treatment of patellar tendinopathy, it is recommended to use an energy between 0.10mJ / mm2

and 0.25mJ / mm2, and and frequency of 4 to 7 Hz with one week intervals - 3 sessions on average-

(6) (13).

Authorship contributions: the authors participated in the creation, writing and final

approval of the original article, as well as in the collection of data.

Funding sources Self-financed.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest in the

publication of this article.

Recibido: January 02, 2021

Aprobado: February 14, 2021

Correspondence: Walter Insuasti.

Adress: Department of Internal Medicine, Centro de Especialidades Ortopédicas.

Mariana de Jesús OE7-02. Quito – Ecuador 170509.

Telephone number: 593 (02)4503252 - 2267490 – 2267491;

E-mail: walter_insuasti@hotmail.com

REFERENCES