ARTICULO ORIGINAL BREVE

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2021 - Universidad Ricardo Palma10.25176/RFMH.v21i2.3709

MOST FREQUENT PEDIATRIC DISEASES IN AN INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT IN MEXICO

ENFERMEDADES PEDIÁTRICAS CON MAYOR FRECUENCIA EN UN AEROPUERTO INTERNACIONAL DE MÉXICO

Augusto Flavio Figueroa Uribe1,a ,Inti Ernesto Bocanegra Cedillo 2,b , Julia Hernández Ramírez 1,c ,Maribel Mújica Hernández 4,d ,Viridiana Cruz Laureano 3,e

1 Hospital Pediátrico Peralvillo SSCDMX, Ciudad de México-México.

2 Hospital de Traumatología y Ortopedia No. 21 del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social,

Monterrey-México.

3 Soljac Medical Division, Estado México-México.

a Pediatric Emergency Physician

b Attending Physician

c Bachelor of Science in Nursing

d Paramedic

e Physician

The frequency in which people travel internationally increases the potential for transmission of infectious diseases. The main causes of disease in children and adolescents vary according to the age group. Prevention is the most important action to take in public health, as it cannot be carried out if the diseases are not detected in a timely manner. The purpose of this study was to identify the most frequent pediatric diseases in the Emergency Medical Service of an international airport in Mexico. The study was observational, descriptive, retrospective and cross-sectional. It is concluded that diseases of digestive (presumed infectious gastroenteritis) and respiratory origin (pharyngitis) were the most frequent. This information can be used not only as a basis for decisions regarding public health, but also for the selection of equipment and supplies to be used in the medical service of an airport (pre-hospital care), in addition to the type of training required by the medical personnel.

Keywords: Disease; Children; Airport. (Source: DeCS BIREME).

RESUMEN

La frecuencia de personas que realizan viajes internacionales aumenta el potencial de transmismión de enfermedades infecciosas; las principales causas de enfermedad en niños y adolescentes varían de acuerdo con el grupo etario. La prevención es la acción más importante en salud pública; no se puede llevar a cabo si las enfermedades no son detectadas oportunamente. El objetivo de este estudio fue identificar las enfermedades pediátricas más frecuentes en el Servicio Médico de Urgencias de un aeropuerto internacional de México; el diseño fue observacional, descriptivo, retrospectivo, y transversal. Se concluye que las enfermedades de origen digestivo (gastroenteritis probablemente infecciosa) y respiratorio (faringitis) fueron las más frecuentes. gastroenteritis probablemente infecciosa. Esta información puede ser utilizada como base para decisiones en el caso de salud pública y por otra parte para selección de equipos e insumos en el servicio médico de un aeropuerto (atención prehospitalaria), además del tipo de capacitación que requiere el personal médico.

Palabras clave: Enfermedad; Niños; Aeropuerto (Fuente: DeCS BIREME).

Since the beginning of the 20th century, there have been trascendental changes in the epidemiological behavior of diseases in Mexico. These, together with ambiental, demographic, economic, social and cultural changes, as well as developments in the healthcare field, have transformed the country’s characteristics and affected the epidemiological profile and characteristics related to the presence of disease or death in the Mexican population (1).

Nowadays, an increasing number of people travel internationally and longer distances at a faster pace (2). This trend is rising, either for professional, social, recreational or humanitarian reasons. By 2030, the number of travelers is expected to increase from 2.5 billion to 5 billion a year, and the number of flights is also expected to increase from 26 million to more than 50 million. In 2010, airlines of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) member states transported 2.5 million passengers and 43 million tons of goods. This field represents roughly 8% of the gross domestic product worldwide and has 32 million workers (3).

Due to the mobility of people by air, international air traffic increases the potential for transmitting infectious diseases from one country to another, but it is unlikely that people living near an airport would become infected. Nonetheless, predicting the future risk of communicable diseases conveys a challenge due to the various shifting and unknown factors (4).

In 2017, an international airport in Mexico conducted 44,732,418 passengers; and, by 2018, this number rose to 47,700,547 passengers (5) with an annual growth rate of 6.6% in regards to the passengers conducted in 2017. Also, in 2019, this airport conducted 50,308,049 passengers, representing a 5.4% growth rate (6). However, these are not the only people who move around inside an airport, since many of them are accompanied by relatives who are not going to travel, and it is imperative to consider all the people who work in the airport: maintenance personnel, licensed taxi drivers, and even pilots and flight attendants. Hence the importance of knowing the diseases that spread in this location for pediatric patients, being the population with the greatest interest in this study due to the vulnerability that this stage of life represents.

According to the data published by the Secretary of Tourism of Mexico, there were 39.3 million international tourists in 2017, 4,218,000 more than that observed in 2016, and equivalent to an annual growth rate of 12% (4).

The main causes of disease in children and adolescents are gingivitis and periodontal disease, ulcers, gastritis and duodenitis, conjunctivitis and acute otitis media. The frequency of these diseases depends on the age group of the patient (children up to one year of age, 1-4 years old, 5-9 years old, 10-14 years old and 15-18 years old) (7). However, there are three diseases that occur irrespective of age, the most frequent ones being respiratory tract infections, intestinal infections and urinary tract infections, in that order (8). Up to 600 million people worldwide (1 in 10) get sick after ingesting contaminated food (bacteria, virus, parasites, toxins and chemicals) every year. Of these people, 420,000 die, including 125,000 children under the age of 5 years (9). In Mexico, intestinal infectious diseases represent the fifth cause of child mortality, while respiratory tract infections are the sixth (10).

Prevention is the most important action to take in public health (11). The lack of knowledge of the most frequent diseases in a particular location deter the implementation of the required measures to detect and treat them in a timely manner. For instance, little is known about the diseases that spread on airports, where people of different nationalities interact. Besides, since there is a growing flow of people, everyone is exposed to different communicable diseases (12,13). Due to the above points, the purpose of the study presented is to identify the most frequent pediatric diseases in the Emergency Medical Service of an international airport in Mexico.

STUDY

Observational descriptive, retrospective, cross-sectional study with heterodemic and non-probabilistic sampling.

Participants were users of the Emergency Medical Service offices of an international airport in Mexico in 2019, with ages ranging from 1 month of age to 17 years and 11 months of age, of both sexes and any nationality, including Mexicans and subjects with injuries and acute and chronic diseases.

Regarding the procedures, data was acquired from the Emergency Medical Service database of the airport, including all records of healthcare services provided and dismissing incomplete, incorrectly and inconsistently filled out records. The database was managed using a spreadsheet processor (Microsoft Excel).

Informed consent of parents or legal guardians of users of the airport’s Emergency Medical Service offices was also obtained.

FINDINGS

The number of medical services registered in total at the airport during 2019 was 26,857, 347 of which (1.3%) were dismissed, leaving 26,510 records, 2097 of which (7.8%) were pediatric patients. Due to the refusal of the patient or relative, 29 of the aforementioned patients did not have a complete record of the medical services received.

Of the 2068 children treated, the majority (1093) were female (52.9%). They were separated by age group, following the classification used in the healthcare sector of Mexico: 55 children up to one year of age (2.7%), 405 children between the ages of 1 and 5 (16.8%), 624 children between the ages of 5 and 10 (30.8%), 637 adolescents between the ages of 10 and 15 (30.2%) and 347 adolescents between the ages of 15 and 18 (19.6%).

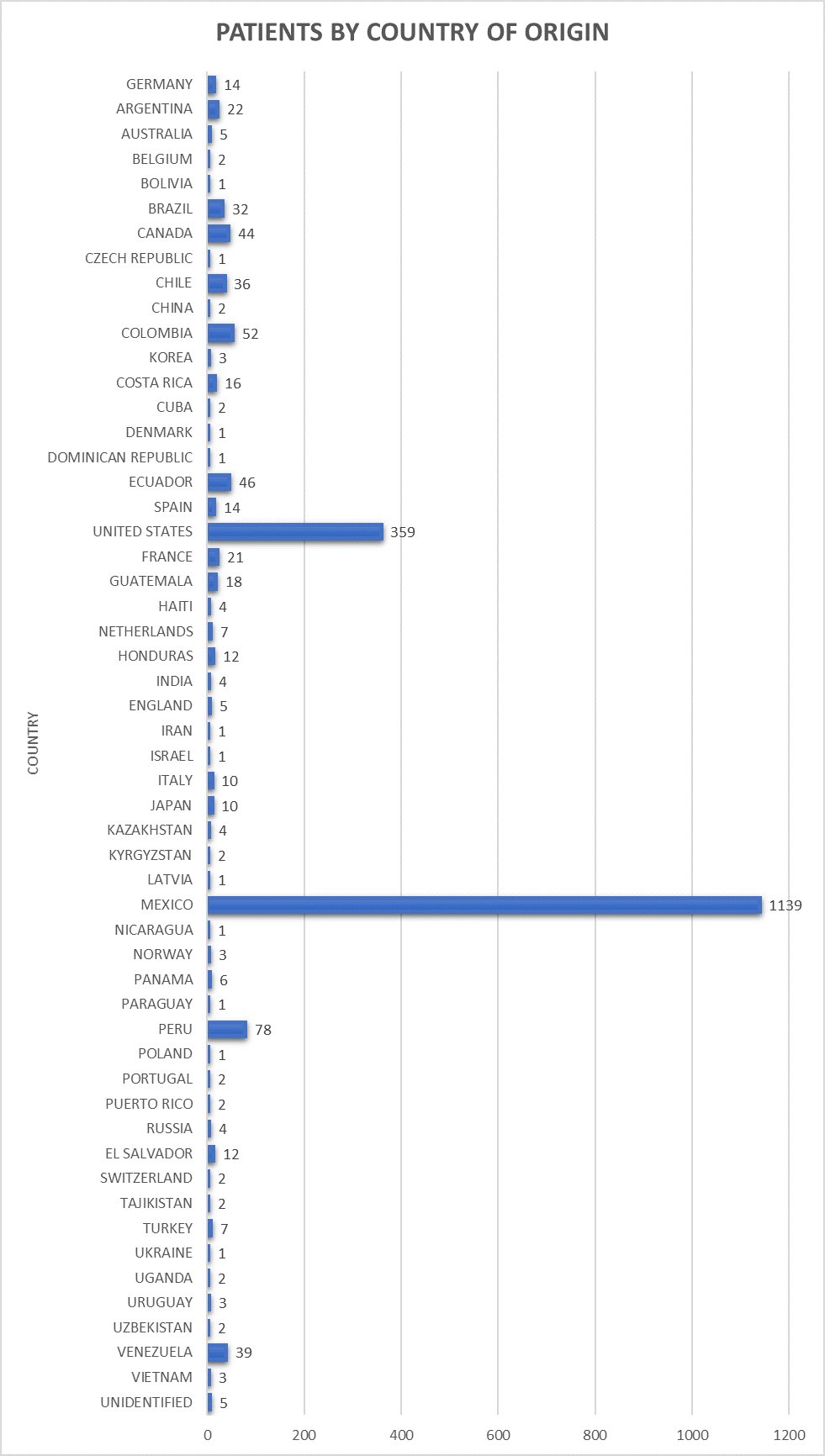

There were 53 nationalities identified including Mexican. However, there were 5 cases in which nationality records were not found. Of the people treated, 55.1% were Mexican and the remaining percentage of other nationalities, American and Peruvian being the most frequent (Figure 1).

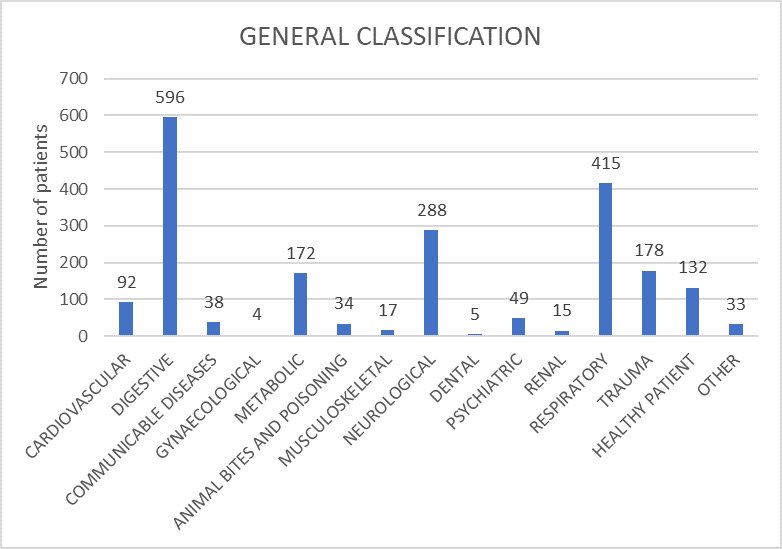

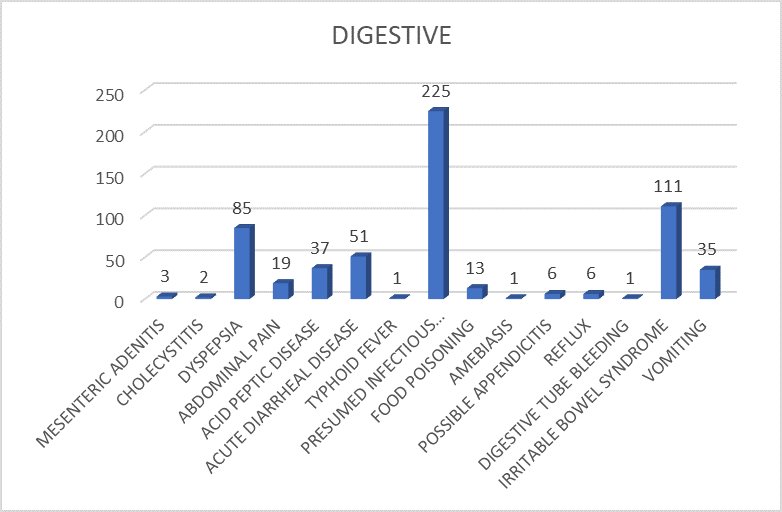

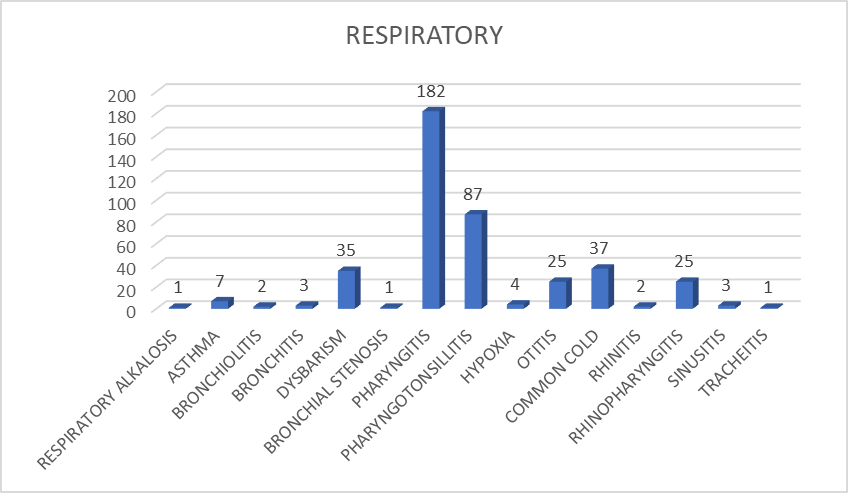

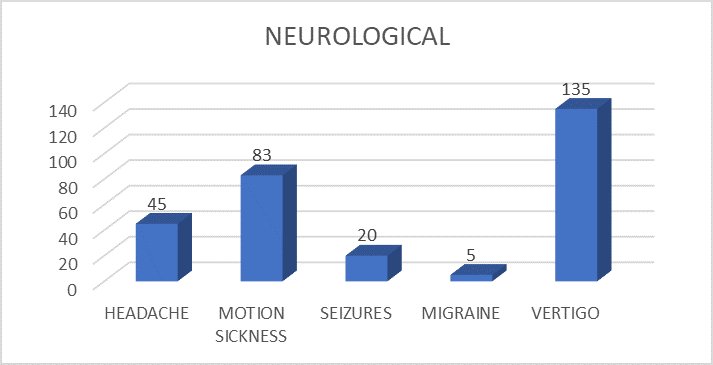

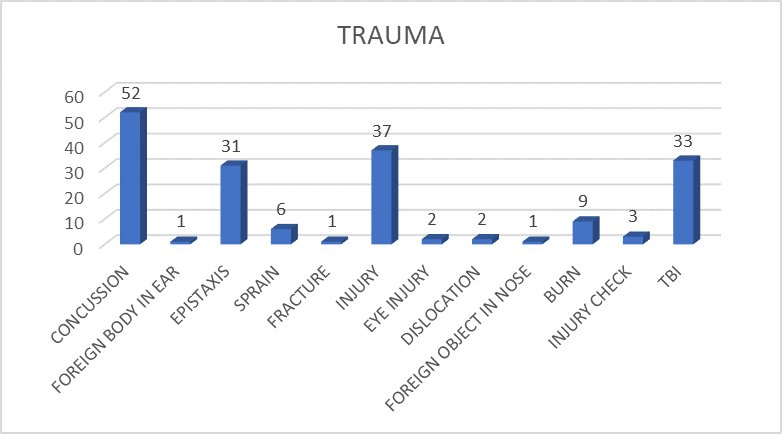

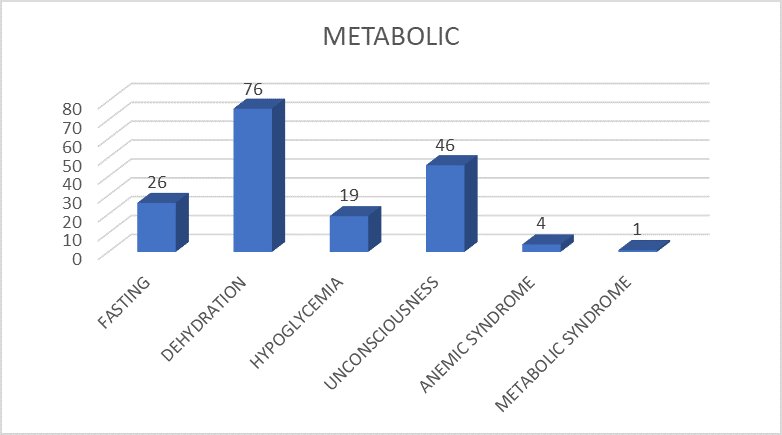

Of the 2068 diseases observed, digestive-type diseases were the most frequent ones covering 28.8% of cases, presumed infectious gastroenteritis being the most prominent among them with 10.9% of cases. The second most frequent were respiratory-type diseases covering 20.1% of cases, pharyngitis being the most prominent among them with 8.8% of cases. Lastly, the third most frequent ones were diseases related to the neurological system covering 13.9% of cases, vertigo being the most common among them with 6.5% of cases. Regarding injuries (8.6%), concussions on different parts of the body had the most occurrence (2.5%). Other causes include metabolic-type injuries (8.3%) in which dehydration was the most common, cardiovascular-type injuries (4.5%), psychiatric injuries such as anxiety attacks (2.4%), urinary tract infections (0.6%) and dysmenorrhea (0.2%) in gynaecological treatments (Figure 2 and 3).

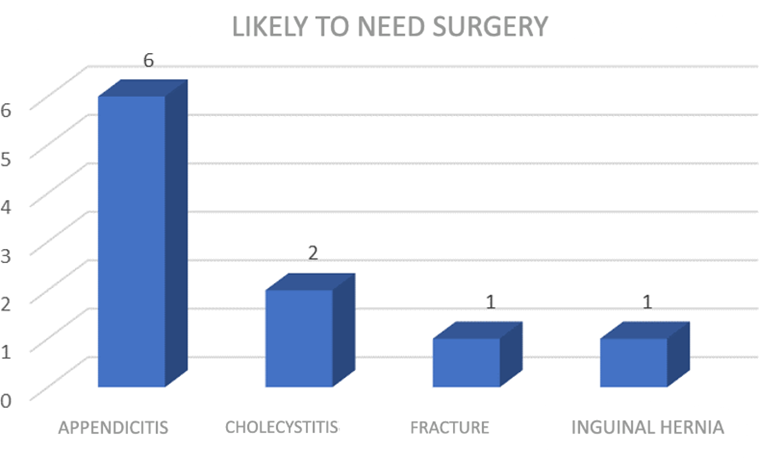

Out of all treatments, there were ten cases which required to be transferred to a hospital due to surgery, representing less than 1% of all cases (0.48%). Six cases of acute appendicitis were found (three of which were Mexican, one Costa Rican, one Peruvian and one Japanese), two cases with acute cholecystitis (both Mexican), a fracture (Mexican) and an inguinal hernia (Mexican) (Figure 3).

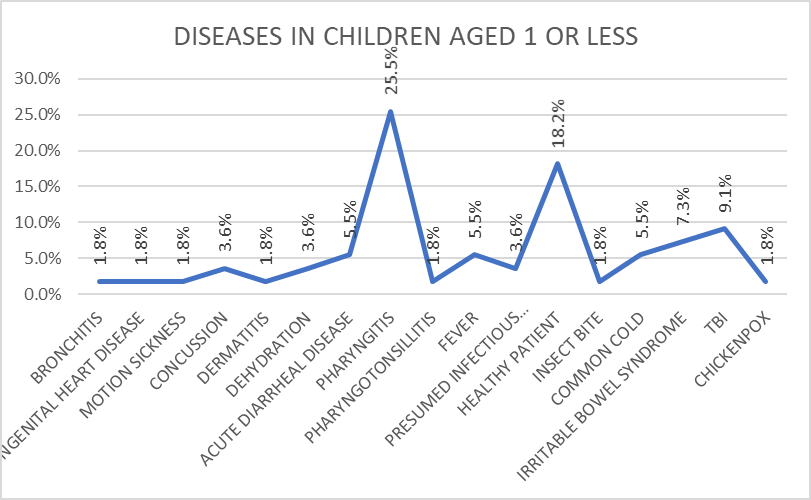

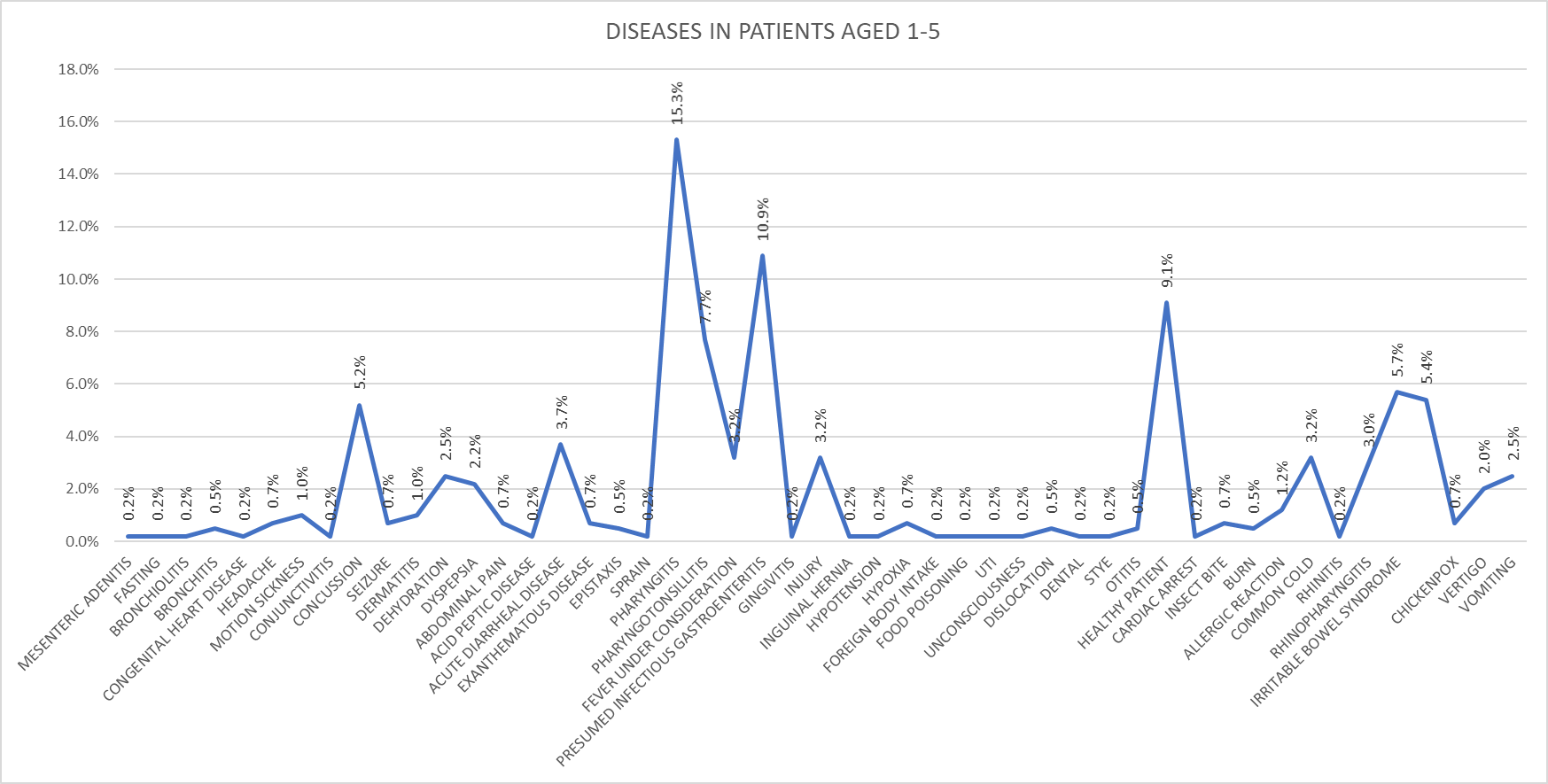

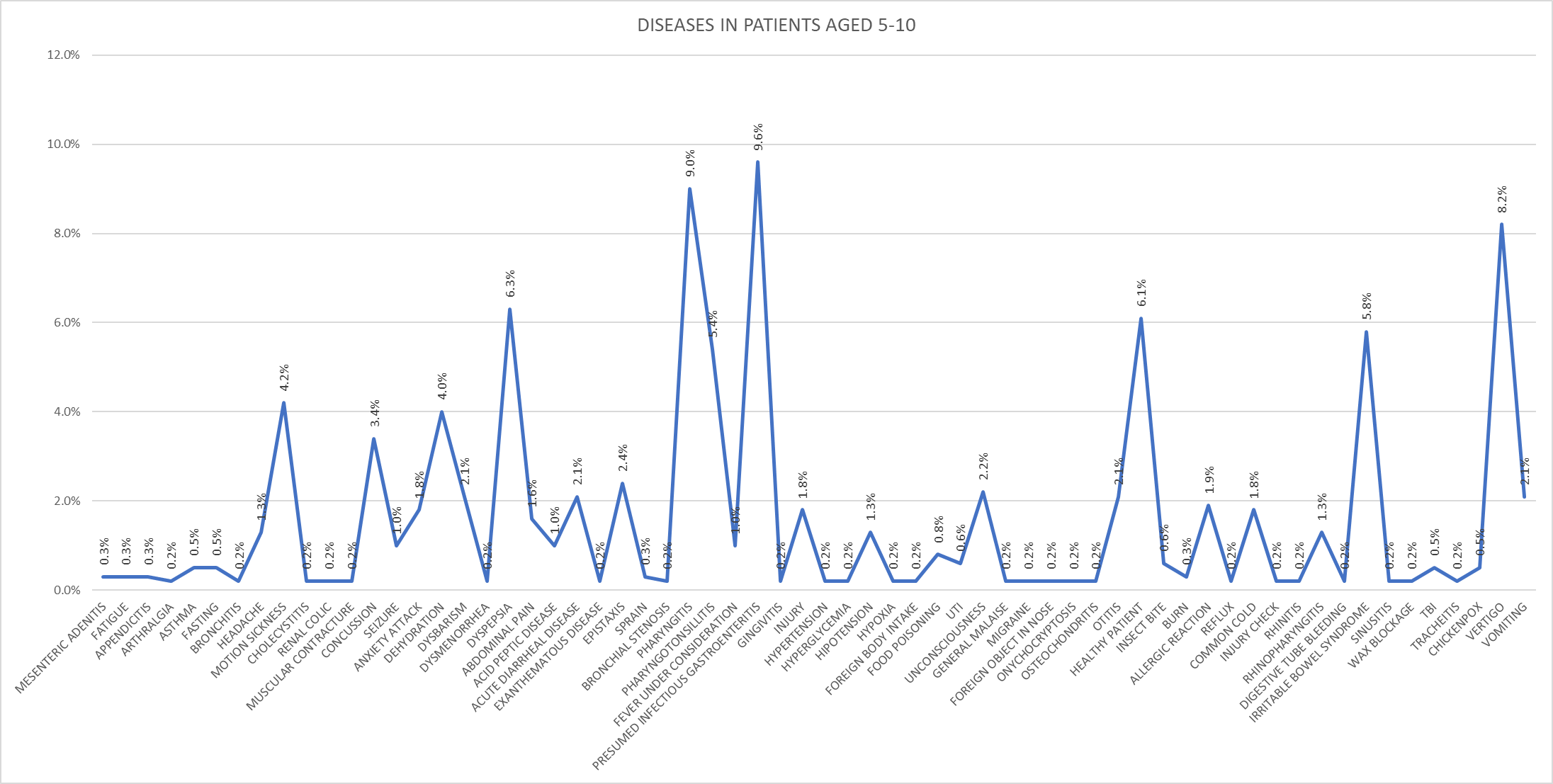

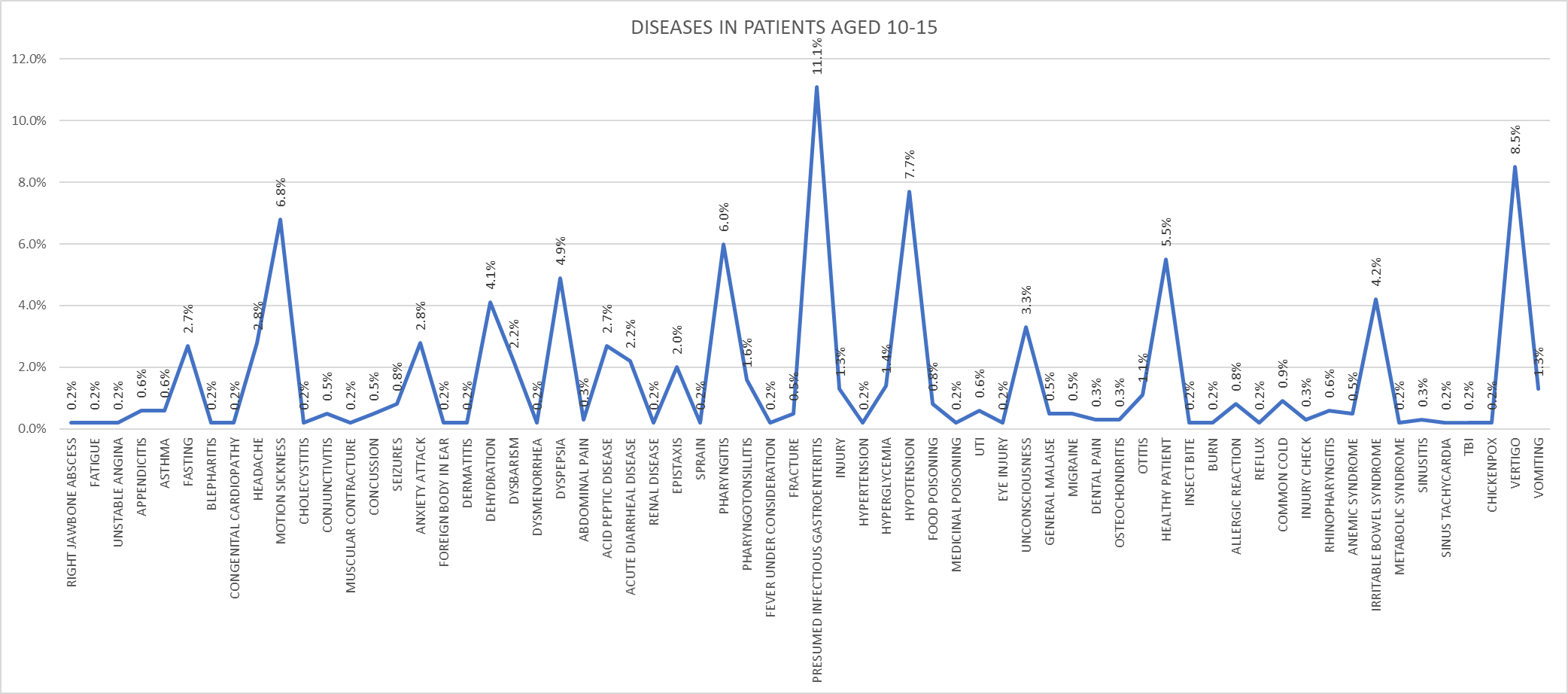

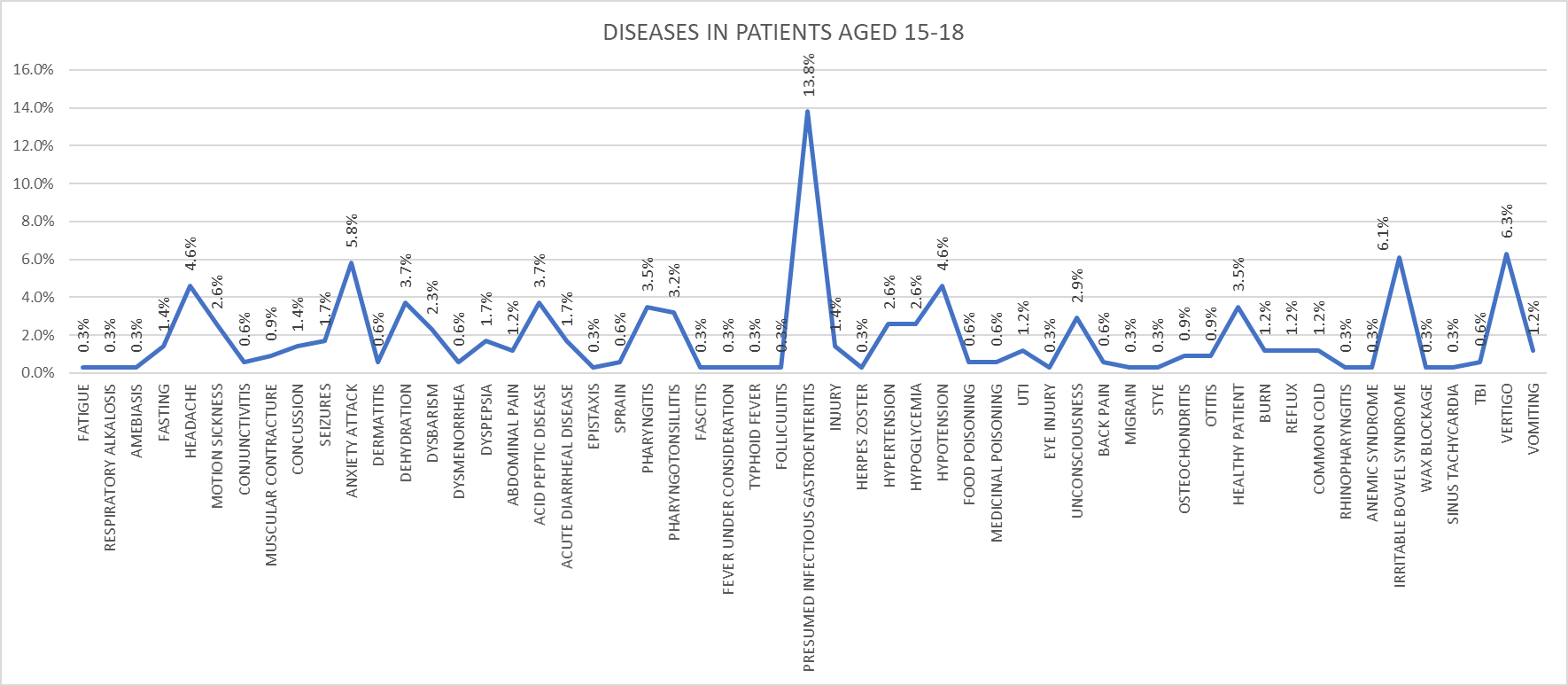

The three most frequent causes of treatment by age group were pharyngitis (25.5%), healthy (18.18%) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (9.09%) in children up to one year of age; pharyngitis (15.3%), presumed infectious gastroenteritis (10.86%) and healthy (9.13%) in children aged 1-5 years; presumed infectious gastroenteritis (9.61%), pharyngitis (8.97%) and vertigo (8.17%) in children aged 5-10 years; presumed infectious gastroenteritis (11.14%), vertigo (8.47%) and hypotension (7.69%) in adolescents aged 10-15 years; and presumed infectious gastroenteritis (13.83%), vertigo (6.34%) and irritable bowel syndrome (6.05%) in adolescents aged 15-18 years (Figure 4).

According to the graphs, TBI and concussions occur more frequently in children under the age of 5 years, with a maximum of 9.1% in children under the age of 1 year (Figure 4).

By their parents’ demand, 132 minors were treated, the reasons being that they thought their kids were “too fidgety”, “too hot” or “without appetite in their last meal” even though none of them had signs of disease, so they were classified as healthy.

|

|

|

|

|

|

DISCUSSION

Since the healthcare records were taken from a Mexican airport, naturally most patients were Mexican (55%). However, people of all continents were treated; out of these 89.1% were from America, 8.8% from Europe, 1.5% from Asia, 0.2% from Oceania and 0.1% from Africa. This proves this location has a large international transit (Figure 1).

Healthy patients were found among the diseases that were treated and responded according to age; these cases decrease as the age range goes up. Anxiety attacks also begin to appear in children aged 5 and up and reach their peak in adolescents aged 15-18 years as shown in 5.8% of their cases. Motion sickness occurs more frequently in adolescents aged 10-15 years as shown in 6.8% of their cases, and headaches are more frequent in children aged 5 and up, reaching their peak in adolescents aged 15-18 years as shown in 4.6% of their cases. Finally, dehydration is present in all age groups, taking up 2.5% to 4.1% of total cases.

Due to the huge flow of people that gather at an international airport, the healthcare service demand is higher, hence the importance of identifying the most frequent diseases that require healthcare services within the airport, in order to pinpoint the risks that may appear while traveling and the measures that can be taken. So far, this kind of research has not been done in other airports to make a comparison, so a broader review of the subject is suggested.

The main diseases found in children and adolescents between the ages of 1 and 18 were gastrointestinal infections and respiratory tract infections; respiratory-type diseases being more frequent for children aged up to one year of age, which match what was observed in that particular age group in Mexican subjects, followed by healthy diagnoses and TBI. This digestive-type disease trend can only be seen in children older than 5 years, which can be attributed to the dietary changes while traveling, especially in international travels, since habits, schedules and foods tend to be very different from those of their country of origin.

Some diseases that stand out by their frequency in the airport were vertigo and anxiety attacks, both of which represent up to 6.52% and 2.36% of cases, respectively. Even though these are small percentages, they can be explained by the travel in and of itself: vertigo occurring as a result of not only the turbulence and landing of planes, but also the car rides on the way to the airport; and anxiety attacks occurring due to the distress that traveling by plane entails.

Regarding patients with suspected diagnosis of possible surgery, an authorization of the parents or guardians was required to relocate them by ambulance to a private or public hospital depending on their personal choice. For foreigners, an authorization to enter the country by the migration department or airport escort of the same department was required. The airport’s healthcare service ends when the patient is admitted into the hospital.

Determining the frequency in which the diseases presented occur in an airport may seem like a simple task, however, a review of a database with incomplete files and a lack of medical notes that explain the complete diagnosis or condition of the patient represents a limitation for this study, especially when the purpose of these internal records does not share the same objective as the present research.

In conclusion, the diseases observed at the airport are similar to those that occur in any community in Mexico, which are a reflection of the medical condition of the whole population, even if it involves people of different nationalities. Diseases of digestive and respiratory origin were the most frequent, presumed infectious gastroenteritis and pharyngitis, respectively.

By appropriately determining the diseases presented, it will be easier to take certain measures in public health that can diminish the spread of communicable diseases, as well as gather the necessary supplies in offices and further training of the health service personnel in order to provide adequate pre-hospital care to pediatric passengers before or after traveling.

Authorship contributions: The authors participated in the conception and design of the

present article, as well as its data collection, analysis and interpretation, critical review

and writing of the final version.

Funding sources: Self-financed.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest for the publication

of this article.

Recibido: January 14, 2021

Aprobado: February 18, 2021

Correspondence: Augusto Flavio Figueroa Uribe.

Address: Hospital Pediátrico Peralvillo SSCDMX, Calz San Simon 14, San Simón

Tolnahuac, Cuauhtémoc, 06920 Tolnahuac, CDMX – México.

Telephone number: 555427275164

E-mail: mandolarian1975@Gmail.com

REFERENCES