ARTICULO ORIGINAL

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2022 - Universidad Ricardo Palma10.25176/RFMH.v22i3.4929

NEONATAL FACTORS MATERNAL FACTORS AND INVASIVE PROCEDURES ASSOCIATED WITH LATE NEONATAL SEPSIS IN THE PERIOD 2011-2020 SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS.

FACTORES NEONATALES, MATERNOS Y PROCEDIMIENTOS INVASIVOS ASOCIADOS A SEPSIS NEONATAL TARDÍA EN EL PERIODO 2011-2020. REVISIÓN SISTEMÁTICA Y METAANÁLISIS.

Allison Poquioma Hernandez1,a, Walter Mosquera Saira1,a, María Loo Valverde2,b, Luis Roldán-Arbieto2,3, Víctor Vera Ponce2,b, Jhony A. De La Cruz-Vargas2,b

1Ricardo Palma University. Lima Peru.

2Biomedical Sciences Research Institute (INICIB), Ricardo Palma University, Lima, Peru

aSurgeon

bDoctor (a)

cMagister

ABSTRACT

Objective: To review, evaluate and synthesize available literature on neonatal and maternal factors and invasive procedures performed on the neonate associated with late neonatal sepsis during the last ten years. Methods: The databases used for the bibliographic search were: Pubmed/Medline, LILACS, SciELO, and Google Scholar. Analytical studies on the research of risk factors for late neonatal sepsis by stages (title, abstract and full text) were selected. The risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. Heterogeneity was assessed and a random-effects meta-analysis was performed for the following risk factors: gender, gestational age, birth weight, Apgar score at 5 min, premature rupture of membranes, route of delivery, use of a central venous catheter, and ventilation. mechanics. The effect was measured with an odds ratio. The certainty of the evidence was determined using the GRADE methodology. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO. Results: Eight studies from 633 records were collected. Heterogeneity was high. 3 male studies OR: 1.97(0.26-14.59) p=0.03; I2 =80%, prematurity 2 studies OR: 2.48 (1.13-5.45); p=0.04; I2 =72%, use of central venous catheter 4 studies – OR: 3.83 (1.07 – 13.71) p<0.01; I2 =89% and mechanical ventilation 4 studies OR: 2.83 (1.42 – 5.68); p<0.01; I2 =86%) were independent factors for the development of late neonatal sepsis. Studies had the lowest comparability assessment score when the risk of bias was applied. The results had low certainty of evidence. Interpretation: Male sex, prematurity, use of central venous catheter, and mechanical ventilation are risk factors for late sepsis.

Keywords: Late neonatal sepsis; Risk factors; Neonatal factors; Maternal factors; Invasive procedures; Systematic review. (fuente: MeSH NLM).

RESUMEN

Objetivo: El presente trabajo se realizó con la intención de Revisar, evaluar y sintetizar literatura disponible sobre factores neonatales, maternos y procedimientos invasivos realizados en el neonato asociados a sepsis neonatal tardía durante los últimos diez años. Métodos: Las bases de datos utilizadas para la búsqueda bibliográfica fueron: Pubmed/Medline, LILACS, SciELO y Google Scholar Se seleccionaron estudios analíticos sobre investigación de factores de riesgo para sepsis neonatal tardía por etapas (título, resumen y texto completo). El riesgo de sesgo se evaluó con la Escala Newcastle Otawa. Se evaluó la heterogeneidad y se realizó un metaanálisis de efectos aleatorios para los siguientes factores de riesgo: sexo, edad gestacional, peso al nacer, Apgar a los 5 min, ruptura prematura de membranas, vía de parto, uso de catéter venoso central y ventilación mecánica. El efecto se midió con odds ratio. La certeza de la evidencia se determinó utilizando la metodología GRADE. El protocolo se registró en PROSPERO. Resultados: Se recopilaron ocho estudios de 633 registros. La heterogeneidad fue alta. 3 estudios sexo masculino OR: 1,97(0,26-14,59) p=0.03; I2 =80%, prematuridad 2 estudios OR: 2,48 (1,13-5.45); p=0.04; I2 =72%, uso de catéter venoso central 4 estudios – OR: 3,83 (1,07 – 13,71) p<0.01; I2 =89% y ventilación mecánica 4 estudios OR: 2,83 (1,42 – 5,68); p<0.01; I2 =86%) fueron factores independientes para el desarrollo de sepsis neonatal tardía. Los estudios tuvieron la puntuación más baja en evaluación de comparabilidad al aplicarse el riesgo de sesgo. Los resultados tuvieron certeza baja de evidencia. Interpretación: Sexo masculino, prematuridad, uso de catéter venoso central y ventilación mecánica son factores de riesgo para sepsis tardía.

Palabras Clave: Sepsis Neonatal; Factores de Riesgo; Recién Nacido; Revisión Sistemática. (fuente: DeCS BIREME).

Introduction

Sepsis is the second leading cause of neonatal mortality, after prematurity. Most perinatal mortality occurs in the neonatal period. (1) Likewise, two-thirds of neonatal mortality occurs in the first week of life. Globally, the death rate from sepsis is 2,202 per 100,000 live births.(1) In Peru, the national neonatal mortality rate was 10 per 100,000 live births in 2017.(2) Sepsis generates a morbidity burden with short- and long-term complications, especially at the neurological level, such as cerebral palsy, delayed psychomotor development, and also prolongs hospital stay and increases hospital costs.(1)

Neonatal sepsis is an infection characterized by bacteremia and is classified according to the time of onset into early and late sepsis.(3.4) The most frequent cut-off points are at 72 hours and 7 days of life. There is currently no global consensus to define the cut-off point. (1,5,6)

Early sepsis is associated with maternal infections such as urinary tract infection (UTI) and chorioamnionitis that are transmitted to the newborn through the birth canal.(7,8) While late sepsis is associated with medical care, it is even considered a nosocomial infection and a major complication in neonatal intensive care units (NICU).(1,9) The incidence of late sepsis differs in infants of certain gestational ages, birth weight, and sex, and is associated with invasive procedures such as endotracheal intubation, total parenteral nutrition, venous catheter, necrotizing enterocolitis, among others.

Early-onset sepsis is associated with group B Streptococci.(10) The pathogens associated with late sepsis vary according to the distribution of each intensive care unit. Therefore, each NICU should study the profile of the pathogens specific to each hospital. Research on the incidence, risk factors, and distribution of pathogens is scarce in Peru.

Applying a risk factor-based approach to guide management decisions is one of the highly effective approaches to reducing neonatal sepsis mortality in high-income countries. It is recommended that in settings with limited resources and a high neonatal mortality rate, a combination of risk factors and clinical signs should serve as a guide for intrapartum and neonatal management. To reduce the burden of disease, it is essential to identify potential risk factors, followed by effective preventive or infection control measures.

For the above reasons, we have the objective of reviewing, evaluating and synthesizing the literature on the risk factors most frequently associated with the development of late neonatal sepsis through a systematic review-type study and subsequent meta-analysis. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis addressing risk factors for the development of late neonatal sepsis.

Evidence from reviews of risk factors for late sepsis from this study will be used for the development of prevention strategies.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis have been reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline.

Information sources and search strategy

An exhaustive literature search was performed in PubMed, SciELO, LILACS, and Google Scholar for studies published in the last 10 years (2011-2020). A comprehensive search strategy was developed that included all possible risk factors for late neonatal sepsis according to the literature review based on MeSH terms and words from the title and abstract involving the following keywords: “late-onset sepsis”, “late onset septicemia”, “late onset bacteremia”, “late onset blood infection”, “infant”, “newborn”, “neonate”, “neonatology”, “risk”, “risk factors”, “risk factor”, “ causality” and “odds ratio”. Search terms within the domain were combined with 'OR' and cross-domain terms with 'AND'. A specific database filter was applied to limit the search to 'last 10 years (2011-2020). No language filter was applied. A search strategy was first developed for PubMed and later adapted for the other databases.

Study

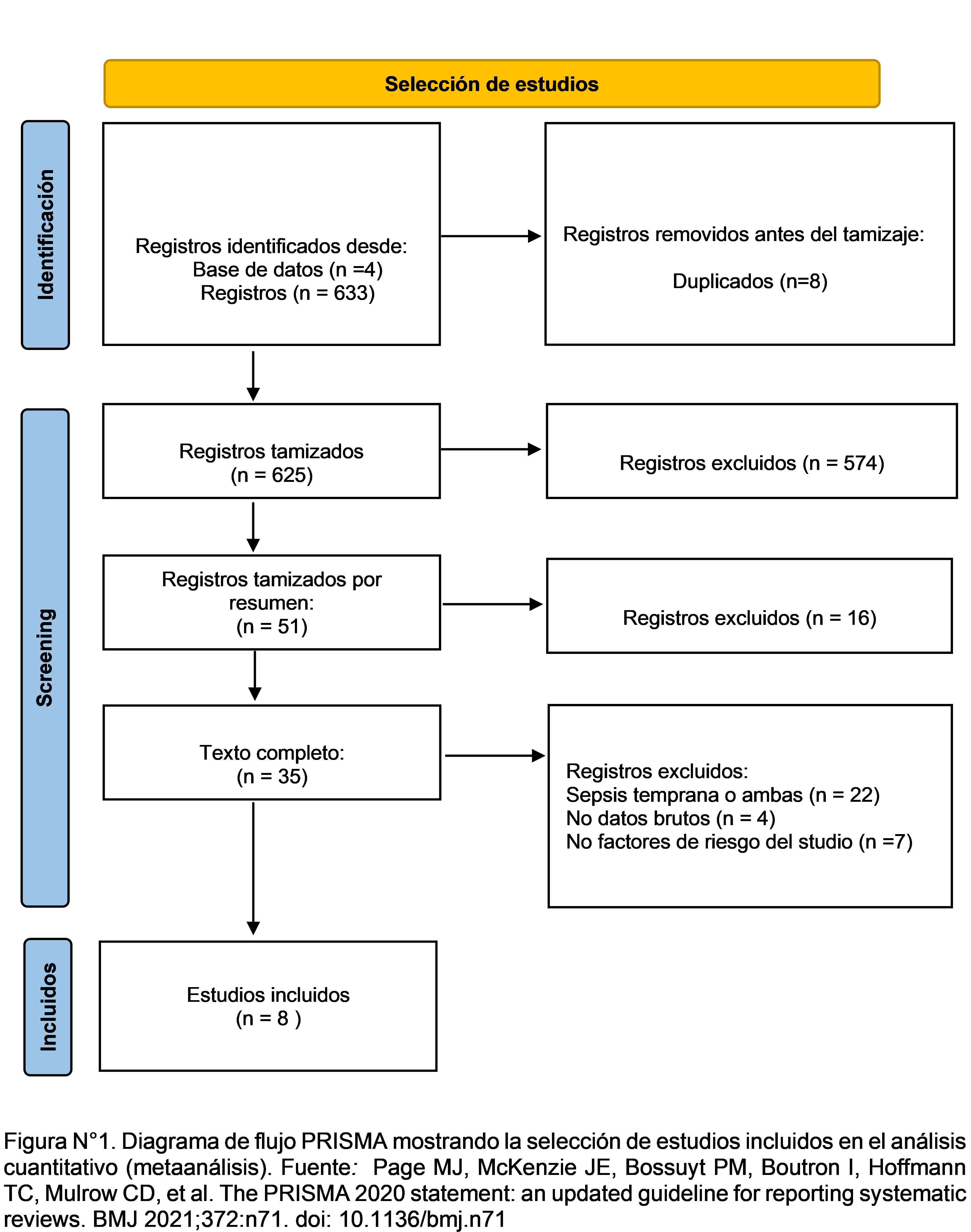

Selection Two authors independently selected studies using three-stage eligibility criteria: title, abstract, and full text. EndNote TM X8 software (Clarivate Analytics, Thomson Reuters, New York) to eliminate duplicates and store the studies for full-text reading. The study selection process was synthesized and outlined using a PRISMA flow diagram in the Shiny web application (https://estech.shinyapps.io/prisma_flowdiagram/) which shows the number of studies included and excluded in each phase of the study selection.

Eligibility

criteria Inclusion criteria:

● Studies evaluating the risk of one or more neonatal factors, maternal factors or invasive procedures to develop late neonatal sepsis.

● Analytical studies that report a comparison of two groups: one with late neonatal sepsis and the other without sepsis.

● Studies that define late neonatal sepsis as that which occurs from 72h of life or more to 28 days of life

● Studies that define cases of sepsis using laboratory criteria (eg culture, hematological parameters)

● Studies were published between 2010 and 2020.

Criteria of exclusion

● Studies not available in their complete version

● Case reports, letters to the author or narrative reviews, and systematic reviews

● Studies that do not have a database

● Studies with unclear diagnostic criteria or that use clinical criteria exclusively

● Studies that evaluate early neonatal sepsis or in general

Data extraction

The data was recorded in a data collection form and later digitized in a Microsoft Excel 2016 data sheet (Microsoft, Washington). For the qualitative analysis, the extraction domains included: title, author, year of publication, study period, country of execution, design, case definition, the definition of late neonatal sepsis, risk factors, and results. Dichotomous raw data for events and non-events, where available, were extracted and converted to OR.

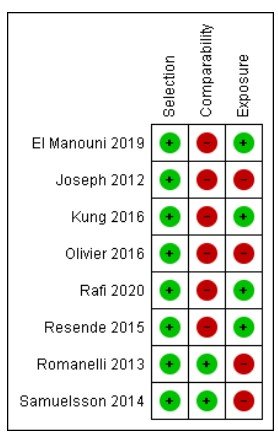

Assessment of the Risk of bias and Certainty of the evidence

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies was used to assess the quality of case-control studies and cohort studies. The NOS evaluates three categories of a given study: selection, comparability, and exposure/outcome. These are scored individually and counted up to a possible total of 9 points. NOS is classified as follows: ≥ 7 for low and 7 for high risk. Risk of bias plots were used to illustrate quality assessment using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4.1 software. (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020).

To assess the certainty of the evidence in this study, the GRADE methodology was used through the GRADE pro online application (https://gradepro.org/), which reports the certainty of the evidence in a summary table. The GRADE methodology assesses four aspects: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirect evidence, and imprecision.

Quantitative analysis

For the statistical analysis, a random-effects meta-analysis was performed in the STATA MP v. program. 14.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) to measure the association between risk factors and late neonatal sepsis. The effect size was measured by Odds ratio. (OR). All variables were dichotomous. The adjusted odds ratio was calculated to minimize confounding bias. The confidence interval was 95% and the value p<0.05. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed and reported using Cochran's Q statistic, I2, and Tau2. I2 from 25 to 50% was considered low, 50-75% moderate, and ≥75% high heterogeneity. The results of the meta-analysis were shown with Forest plot type diagrams. Tables were provided for the characteristics of the included studies and for the results of the quality assessment. Publication bias should be developed if and only if there are at least 10 studies in the meta-analysis using Funnel Plot diagrams, which is why publication bias is not assessed in this study.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 633 studies were found. 8 duplicates were removed and 625 titles were reviewed. Of these, 574 titles were excluded and 51 abstracts were screened. Of these, 35 full-text registries were examined and 8 studies met the inclusion criteria for this review. The reasons for the exclusion of 27 full-text records were: no study of risk factors, another type of sepsis, absence of risk factors studied, and lack of data. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

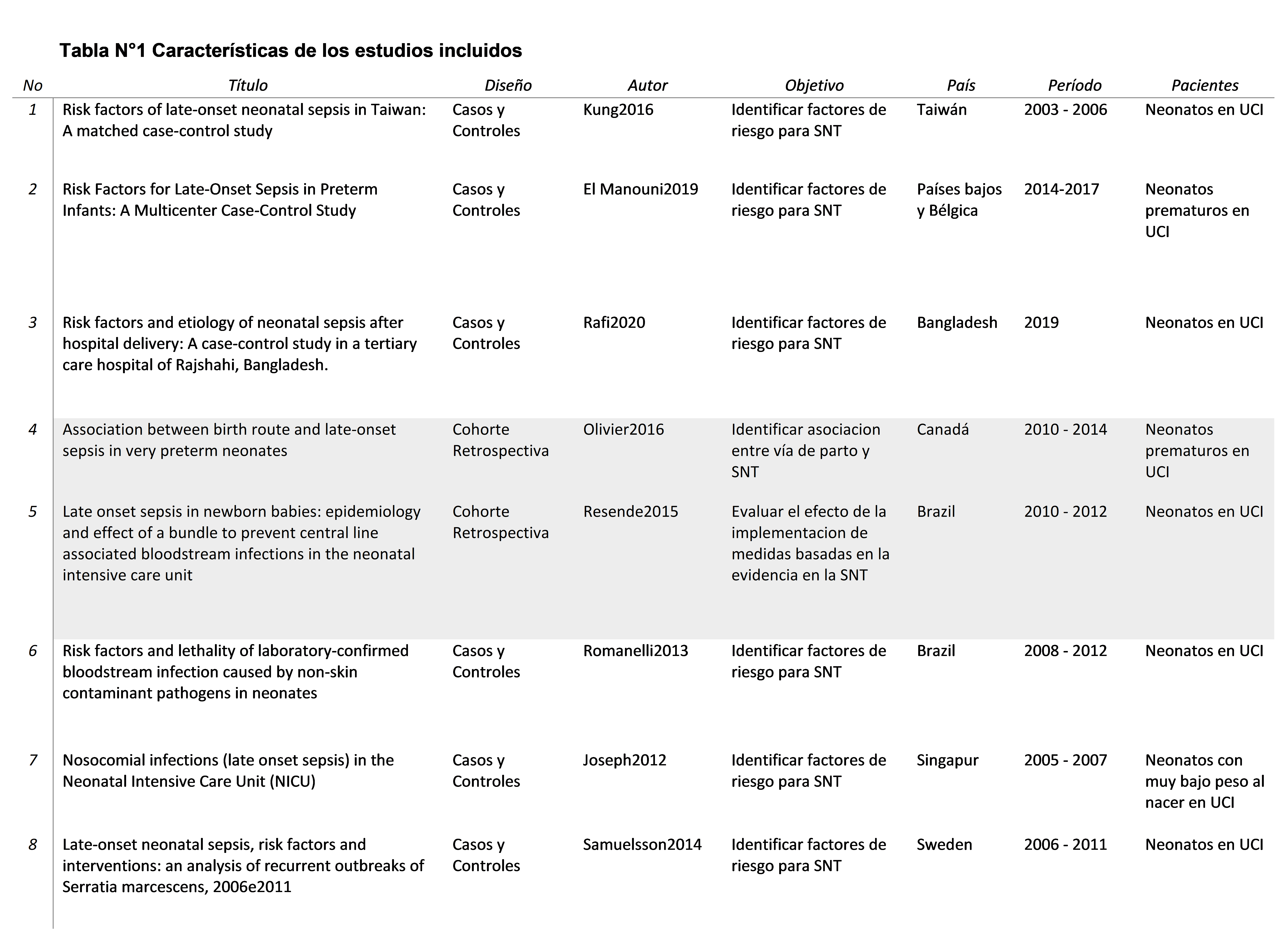

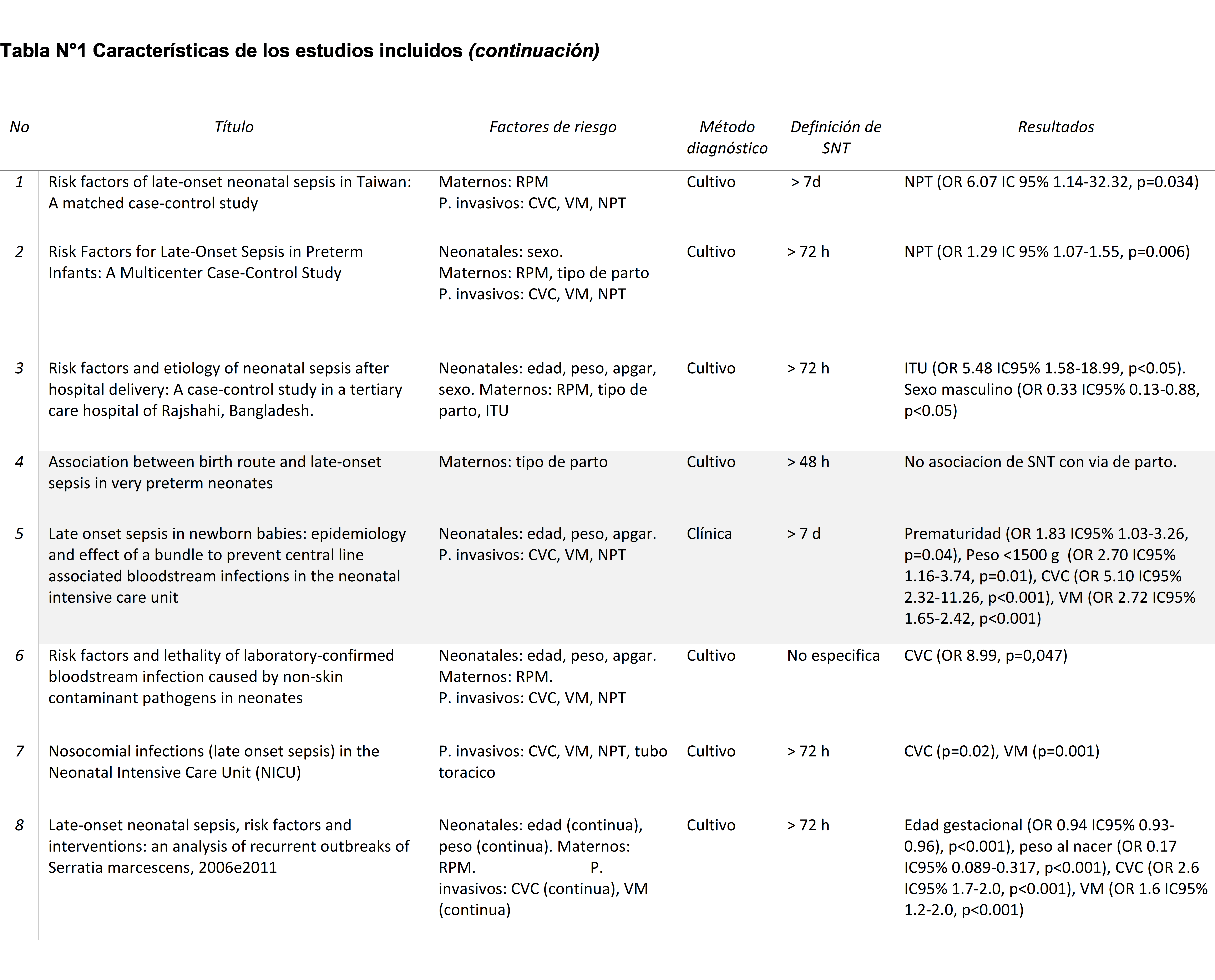

Regarding the design, of the 8 studies, 6 were cases and controls, 1 retrospective cohort, and 1 prospective cohort. Six studies were done in term infants and 2 in preterm infants. All studies were carried out in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. According to the definition of sepsis, 2 studies defined it as that which appears after 7 days, 4 studies took 72h as the cut-off point, and 1 did not specify. Likewise, there were variations in the guidelines used to diagnose neonatal sepsis: 8 studies required positive cultures to confirm neonatal sepsis, and 1 applied clinical criteria. A summary of the characteristics of the included studies can be seen in Table 1.

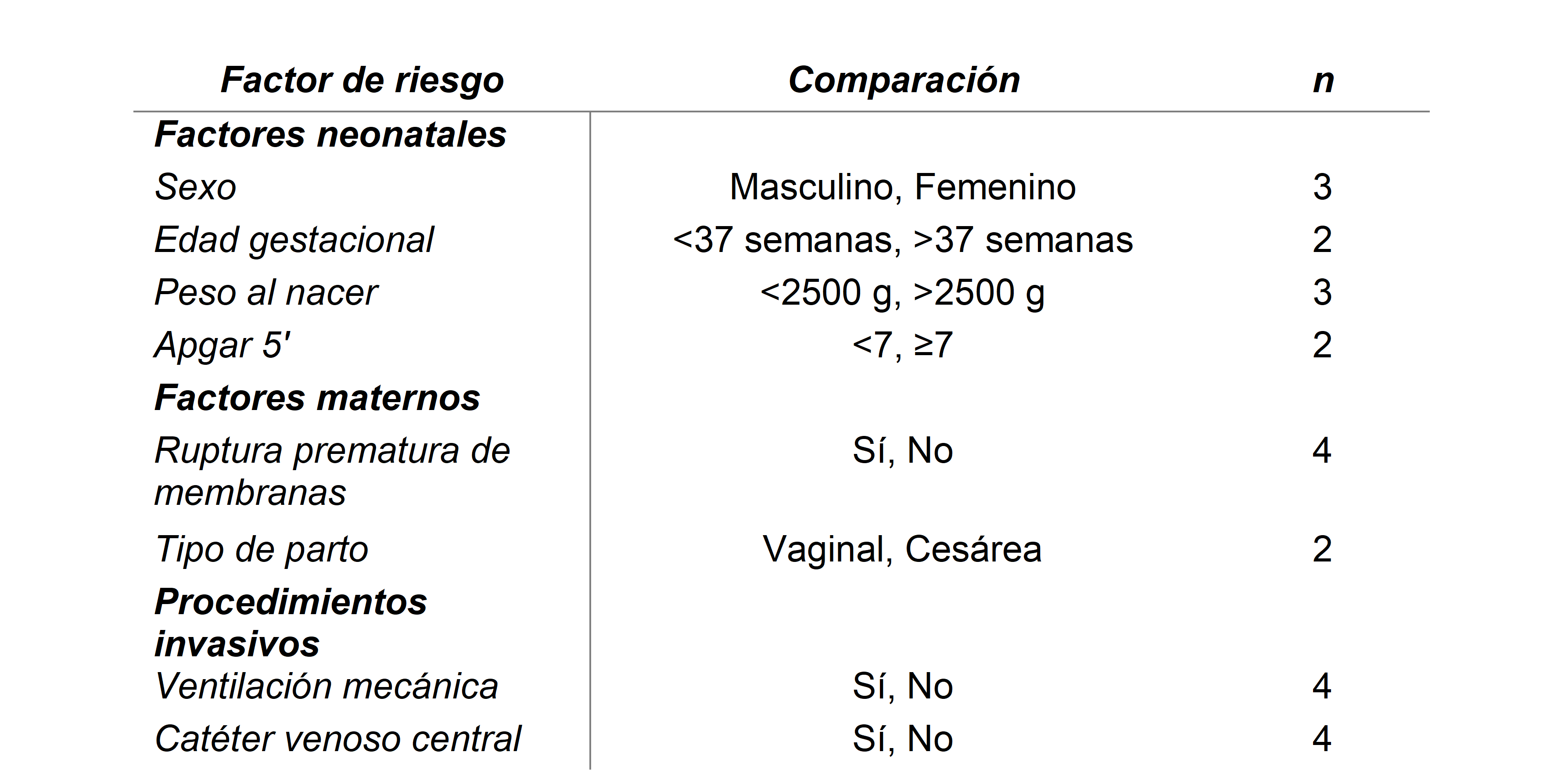

Risk Factors

Four neonatal factors, 2 maternal factors, and 2 invasive procedures associated with late neonatal sepsis were studied. The most frequently described risk factors are premature rupture of the membranes, use of a central venous catheter, and the need for mechanical ventilation (4 studies each). A meta-analysis was performed for a total of 8 factors. The details of the factors included in the meta-analysis have been provided in Table 2.

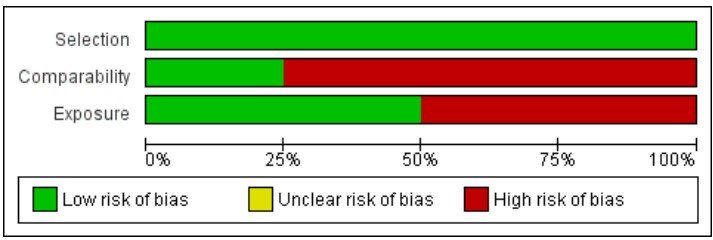

For neonatal factors, a meta-analysis was performed for four risk factors (Figure 2) of which, male sex (3 studies – OR: 1.97 (0.26-14.59); p=0.03; I2 =80%), and prematurity (2 studies – OR: 2.48 (1.13-5.45); p=0.04; I2 =72%), significantly increased the odds of late neonatal sepsis.

Factors that increased the probability of late neonatal sepsis but were not significant in the meta-analysis were low birth weight (3 studies – OR: 2.50 (1.20-5.18); p=0.14; I2 =53%) and low Apgar at 5' (2 studies – OR: 1.47 (1.01-2.13); p=0.32; I2 =18%).

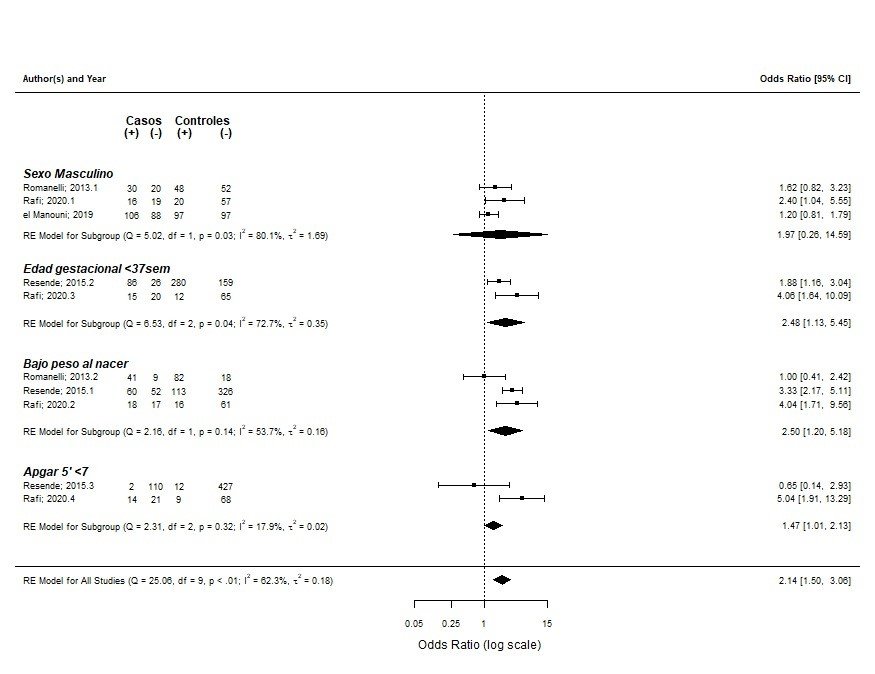

For maternal factors, a meta-analysis was performed for 2 factors. Premature rupture of membranes (4 studies – OR: 1.04 (0.76 – 1.42); p=0.16; I2 =0%) increased the incidence of late neonatal sepsis. Vaginal delivery was not associated with late neonatal sepsis (3 studies – OR: 0.94 (0.78 – 1.12); p=0.32; I2 =20%) (Figure N°3).

Invasive procedures that were significantly associated with late neonatal sepsis were the use of a central venous catheter (4 studies – OR: 3.83 (1.07 – 13.71); p<0.01; I2 =89%) and the need for mechanical ventilation (4 studies – OR: 2.83 (1.42 – 5.68), p<0.01, I2 =86%). (Figure 3).

Assessment of risk of bias

When performing a quality assessment using the NOS for cases and controls, four studies were rated good, two fair studies, and two poor studies). The category with the lowest rating was “comparability”. None of the studies reported the use of a reporting checklist to describe their studies.

Certainty of the evidence

The GRADE methodology was used to assess the certainty of the evidence for this systematic review. We found that for all risk factors (neonatal, maternal, and invasive procedures), the evidence was of low certainty. This was mainly due to the risk of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision of the evidence.

Discussion

This meta-analysis aimed to identify neonatal and maternal risk factors and invasive procedures performed on the newborn, such as central venous catheter placement, mechanical ventilation, parenteral nutrition, and chest tube, associated with the development of late neonatal sepsis described in medical literature for the last ten years. The study showed that male gender, prematurity, the use of a central venous catheter, and the need for mechanical ventilation significantly increased the odds of developing late neonatal sepsis. The results are consistent with other studies.(11-15) Knowing the risk factors would help in the prevention and early identification of late neonatal sepsis. There was variation in the case definitions as well as in the definition of late neonatal sepsis in the studies included in our review. Similar variability has been found in the world literature on late neonatal sepsis. Most are defined as cases those neonates with symptoms and signs in addition to positive blood culture, and others are defined as cases those neonates with symptoms and signs and with laboratory tests without the need for a positive culture. Another difference between the studies was the cut-off point in time to define neonatal sepsis. Six studies define late sepsis as that which appears after 72 hours of life, which coincides with most antecedents. (11,16,17,18) While two studies define it as that which appears after 7 days to 28 days of life.(9,19,20)

We found a higher incidence of sepsis among male neonates, possibly based on the 'male disadvantage hypothesis'. Regarding maternal factors, it was found that premature rupture of membranes increased the incidence of late neonatal sepsis, but it was not an independent risk factor, also described by other authors.(10,19,17,20) No association was found between the route of delivery and late neonatal sepsis as in other studies.(21)

Male neonates are more sensitive to adverse perinatal and postnatal environmental conditions and are more likely to be born preterm and with lower birth weight, both of which increase the risk of neonatal sepsis.(1) Higher initial respiratory support required by male neonates may lead to worse outcomes.(22,23-25)(22,23–25)

Prematurity has also been implicated as a significant risk factor, as in other studies.(7,9,26,27) In this study, low birth weight and low Apgar at 5' increased the incidence of late neonatal sepsis, although it was not an independent factor. This finding contrasts with some antecedents.(16,17,28) It is probably due to the low number of compared studies.

Regarding maternal factors, it was found that premature rupture of membranes increased the incidence of late neonatal sepsis, but it was not an independent risk factor, as described by other authors.(10,17,19,20) No association was found between the route of delivery and late neonatal sepsis as in other studies.(twenty-one)

As found in the medical literature and various studies, we identified that the use of invasive devices such as central venous catheters and endotracheal tubes are independent factors of late neonatal sepsis.(16-18,29)(16-18,29)

The present study presented some limitations. The limited number of studies available, as well as the type of studies included, correspond to cohorts and cases, and controls, which could increase the risk of bias. Likewise, we found high heterogeneity between the studies. As strengths, we have that the present study represents the first meta-analysis on factors associated with late neonatal sepsis, which highlights the need for further research on this topic. This work has followed the guide for systematic reviews PRISMA. and has been subjected to the GRADE evaluation. The level of evidence ranged from very low (4 studies) to low (4 studies).

Conclusions

In this systematic review of observational studies, it was found that male or premature newborns have a higher risk of developing late neonatal sepsis.

Among the invasive procedures, we found that the use of a central venous catheter and the need for mechanical ventilation are independent factors of late neonatal sepsis.

No association was found between birth weight, low Apgar at 5 minutes, maternal history of premature rupture of membranes or vaginal delivery, and the development of late sepsis in newborns.

There is a lack of evidence on the risk factors associated with late neonatal sepsis in Peru. Recognition of risk factors should help develop a preventive strategy against neonatal sepsis.

Recommendations

Efforts to reduce the neonatal mortality rate should focus on the management and prevention of prematurity, as well as paying special attention to male newborns because they are more vulnerable. It is recommended to optimize surveillance of nosocomial infections through management protocols for invasive procedures to reduce the incidence of neonatal sepsis. Solid research is required in the country of Peru in this regard to obtain updated statistics.

Authorship contributions: Allison Poquioma: data collection, study design, statistical interpretation, writing of the protocol and manuscript. Walter Mosquera: data collection. María Loo Valverde: study design, protocol review, manuscript review, Luis Roldán: statistical analysis, Víctor Vera: protocol review, supervision, Dr. Jhony De La Cruz: protocol review, manuscript review and supervision.

Funding sources: Self.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Received: May 05, 2022

Approved: June 15, 2022

Correspondence: Allison Poquioma Hernandez.

Address: Av. Alfredo Benavides 5440, Santiago de Surco.

Telephone number: 951209937

E-mail: apoquiomah@gmail.com

Article published by the Journal of the faculty of Human Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University. It is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creatvie Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, CC BY 4.0(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0/), that allows non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. For commercial use, please contact revista.medicina@urp.edu.pe.

REFERENCES