ORIGINAL ARTICLE

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2023 - Universidad Ricardo Palma10.25176/RFMH.v23i2.5642

QUALITY OF LIFE WITH AND WITHOUT SPHINCTER-

CONSERVING SURGERY FOR REAL CANCER

CALIDAD DE VIDA CON Y SIN CIRUGÍA CONSERVADORA DE ESFÍNTERES POR CÁNCER DE RECTO

José Manuel Carlos Segura-González

1,a,

Samantha Isabel Hernández-Muñoz

1,a,

Samantha Isabel Hernández-Muñoz

1,a,

1,a,

Arturo García-Galicia

2,b,

Esmeralda Gracián-Castro

2,b,

Esmeralda Gracián-Castro

3,c,

3,c,

Iris Isamar Tiscareño-Lozano

1,a,

María Guadalupe Vera-Sánchez

1,a,

María Guadalupe Vera-Sánchez

1,a,

1,a,

Álvaro José Montiel-Jarquín

2,d,

Nancy Rosalía Bertado Ramírez

2,d,

Nancy Rosalía Bertado Ramírez

2,e

2,e

1 Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Centro Médico Nacional, Hospital de Especialidades “Gral. Div. Manuel Ávila Camacho”,

Departamento de Cirugía Digestiva. Puebla, Mexico.

2 Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Centro Médico Nacional, Hospital de Especialidades “Gral. Div. Manuel Ávila Camacho”,

Dirección de Educación e Investigación en Salud. Puebla, Mexico.

3 Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla, Puebla de Zaragoza, Mexico.

a Physician specialized in General Surgery.

b Pediatrician. Master in Medical Sciences and Research.

c Social Service intern.

d Physician specialized in General Surgery. Master in Medical Sciences and Research.

e Physician specialized in Neurology.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of death worldwide, with an incidence of 10.2%. The treatment of CRC has evolved over the past 25 years. Two surgical procedures are used: abdominoperineal resection (APR) and low anterior resection (LAR) and ultra-low anterior resection (ULAR). The recurrence rate and quality of life are similar between these approaches. Objective: To compare the quality of life of rectal cancer patients treated with abdominoperineal resection versus conservative sphincter-preserving surgeries: low anterior resection (LAR) and ultra-low anterior resection (ULAR) at UMAE of Puebla. Methods: A comparative, observational, cross-sectional study was conducted on CRC patients treated between 2015 and 2019 at a tertiary-level hospital in Puebla. Two groups were formed: those managed with APR and those managed with LAR/ULAR. The EORTC QLQ-CR29 scale and EuroQol were applied. Descriptive statistics and the Mann-Whitney U test were used for comparisons. Results: A total of 26 patients were recruited, 18 with APR and 8 with LAR/ULAR. The mean quality of life score in the APR group was 73.72 (SD 16.92, minimum 31.46, maximum 95.09), and in the LAR/ULAR group was 56.22 (SD 6.29, minimum 47.51, maximum 68.96), with a p-value of 0.005. Conclusions: There is no significant difference in the quality of life of CRC patients operated with APR, LAR, and ULAR (non-conservative and conservative approaches).

Keywords: Neoplasm, quality of life, anastomosis, surgical. (Source: MeSH – NLM).

RESUMEN

Introducción: El cáncer colorrectal (CCR) es el tercer cáncer más frecuente y la segunda causa principal de muerte a nivel mundial con una incidencia 10,2%. El tratamiento del CCR ha cambiado durante los últimos 25 años. Se utilizan dos manejos quirúrgicos: la resección abdominoperineal (RAP) y la resección anterior baja (RAB) y la ultra baja (RAUB). La tasa de recidiva y la calidad de vida son similares. Objetivo: Comparar la calidad de vida de los pacientes con cáncer de recto tratados con resección abdominoperineal vs resecciones conservadoras de esfínteres: anterior baja y ultra baja en la UMAE Puebla. Métodos: Se realizó un estudio comparativo, observacional, transversal en pacientes con CCR atendidos durante 2015-2019 en un hospital de 3er nivel en Puebla. Se formaron dos grupos: los manejados con RAP y los manejados con RAB/RAUB. Se aplicó la escala EORT QLQ CR-29 y EuroQol. Se aplicó estadística descriptiva y U de Man-Whitney para comparaciones. Resultados: Se reclutaron 26 pacientes, 18 manejados con RAP y 8 con RAB/RAUB. Se registró una CV media en el grupo RAP de 73,72 (DE 16,92, mínimo 31,46, máximo 95,09) y en el grupo RAB/RAUB de 56,22 (DE 6,29, mínimo 47,51, máximo 68,96), con un valor de p=0,005. Conclusiones: No hay diferencia significativa en la calidad de vida de los pacientes con CCR operados por RAP, RAB y RAUB (abordaje no conservador y conservador).

Palabras clave: Neoplasia, calidad de vida, anastomosis quirúrgica. (Fuente: DeCS – BIREME)

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of death worldwide, with an incidence of 10.2% (1,2).

The five-year survival rate in high-income countries in 2020 ranged from 59% to 70.9% of the affected population (3,4).

While the most common presentation occurs in individuals over 70 years old, the incidence among individuals under 50 years old has increased up to 1.8% per year

(5).

This increase affects the productive population of the country and the life expectancy of 75 years (6,7).

The anatomy of the rectum poses a challenge for surgeons: inadequate dissection from the midline towards the endopelvic fascia can lead to local recurrence of the

disease. Improper avascular lateral dissection compromises autonomic nerves and causes impotence in men, general bladder dysfunction, as well as intestinal motility

disorders and body image disturbances. (8,9).

The treatment of CRC has changed over the past 25 years (10).

The goal of colorectal surgery is to maintain clear margins free from malignancy (8).

Multimodal therapy and surgery with clear margins have shown low rates of local recurrence and improved long-term survival (11,12).

Two surgical approaches are used: abdominoperineal resection (APR) involves complete anorectal removal, with permanent residual colostomy and no preservation of

anal sphincters (13).

In contrast, low anterior resection and ultra-low anterior resection (LAR/ULAR) involve colorectal anastomosis and sphincter preservation

(14,15).

The presence of permanent stomas decreases the quality of life (QoL) for patients managed with APR (15).

On the other hand, patients undergoing LAR/ULAR have a risk of developing low anterior resection syndrome, which significantly affects the patient's long-term QoL

(16,17).

The indications for sphincter-preserving surgery have increased in order to avoid a permanent stoma (18).

These patients experience intestinal symptoms such as incomplete evacuation, loose stools, and/or gas incontinence after surgery, which also diminishes their QoL

(19,20).

However, recent reports indicate similar rates of recurrence and QoL between sphincter-conserving surgery and APR (18,19).

All of this represents a dilemma in choosing the surgical approach (20).

Inter-sphincteric resections and reduced distal margins are currently areas of exploration but with limited technological availability

(21,22).

The high incidence of complications is due to extensive resection, leaving the pelvic cavity exposed to infections (23,24).

The objective of this study was to compare the QoL in patients with CRC managed with APR versus those with sphincter preservation (LAR/ULAR) at a tertiary-level

hospital of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social.

METHODS

Design and study area

A comparative, prospective and retrospective, cross-sectional study was conducted on patients treated at a tertiary-level hospital of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social in Puebla, Mexico, during 2015-2019.

Population and sample

Using non-probabilistic convenience sampling, 26 medical records of 47 patients who underwent surgery for CRC with APR or LAR/ULAR and met the inclusion criteria

were included. Those who passed away, discontinued follow-up through outpatient visits, or did not answer the phone call were excluded.

APR was considered for cases with complete rectal resection in tumors located five cm below the anal margin, using abdominal and perineal approaches, with permanent

residual colostomy and no preservation of anal sphincters.

Sphincter-preserving surgeries included LAR/ULAR for tumors located up to six and two cm from the anal margin, respectively, performed through laparotomy. Both procedures

involved colorectal mechanical anastomosis with or without a protective stoma.

Variables and instruments

Age and gender of CRC patients were recorded.

The “European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire - Colorectal Cancer Module 29” (EORTC QLQ-CR29) was administered. It

consists of four functional scales (body image, sexual function, sexual enjoyment, future perspectives) and seven symptom scales (urinary problems, gastrointestinal

problems, chemotherapy side effects, sexual dysfunction, defecation problems, weight loss, stoma-related problems).

The EuroQol questionnaire, consisting of five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression), each with three levels (no

problems, some problems or moderate problems, and severe problems), was also administered (22,24).

The scores from the application of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 were stratified as follows: 100-67.85 = good quality of life and 67.84-35.711 = poor quality of life. For EuroQol,

a score of 1-0.757 was considered good quality of life and 0.756-0.0514 was considered poor quality of life (24).

Procedures

The required information was collected from the patients' records who met the selection criteria.

After obtaining informed consent in the outpatient clinic, the EORT QLQ CR-29 and EuroQol questionnaires were administered to the patients.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis of the data was conducted. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-parametric and unrelated ordinal qualitative variables.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Local Health Research Committee No. 2101 of the Mexican Social Security Institute. Patient information was handled with strict confidentiality and used solely for research purposes. No conflicts of interest were reported.

RESULTS

26 out of a total of 47 patients were surveyed; 18 could not be contacted (did not answer the phone and/or changed address without traceability), two passed

away, and one declined to participate in the study. The gender distribution was 14 females (54%) and 12 males (46%). The mean age was 61.76 years (standard

deviation (SD) 11.99, minimum 35, maximum 82).

Eight (30.8%) patients reported having diabetes mellitus, six (23.1%) had hypertension, and one patient (3.8%) had other respiratory, cardiac, rheumatological,

and inflammatory bowel diseases in each entity.

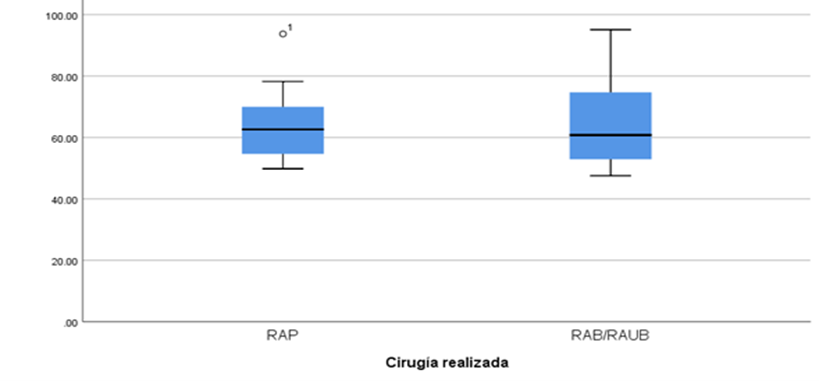

Patients who underwent APR had a mean QoL of 73.72 (SD 16.92, minimum 31.46, maximum 95.09). Those with LAR/ULAR had a mean of 56.2 (SD 6.29, minimum 47.51,

maximum 95.09). The Mann-Whitney U test yielded a p-value of 0.952 (95% CI). See Figure 1

Figure 1. Quality of life in patients with rectal cancer.

Abbreviations: APR: abdominoperineal resection, LAR: low anterior resection, ULAR: ultralow anterior

resection. EORTC QLQ-C29 application score: good: 100-67.85, bad: 67.84-35.71.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to all variables, resulting in a p-value <0.05. When comparing the quality of life between patients treated with APR and LAR/ULAR, no significant differences were found. The details are shown in Table 1

Table 1. Quality of life according to symptoms.

|

|

Non-Conservative APR |

Conservative LAR/ULAR |

Difference in medians |

U |

P |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Body image |

Med |

0.79 |

0.95 |

0.16 |

61.50 |

0.553 |

|

|

Min |

0.5 |

0.41 |

|||||

|

Max |

1 |

1 |

|||||

|

Sexual health |

Med |

0.15 |

0.12 |

0.03 |

67.00 |

0.762 |

|

|

Min |

0.12 |

0.12 |

|||||

|

Max |

0.81 |

1 |

|||||

|

Urinary symptoms |

Med |

0.87 |

0.91 |

0.04 |

69.00 |

0.865 |

|

|

Min |

0.58 |

0.74 |

|||||

|

Max |

1 |

1 |

|||||

|

Gastrointestinal symptoms |

Med |

0.90 |

0.95 |

0.05 |

51.00 |

0.230 |

|

|

Min |

0.25 |

0.64 |

|||||

|

Max |

1 |

1.66 |

|||||

|

Chemotherapy symptoms |

Med |

0.99 |

0.95 |

0.04 |

45.50 |

0.119 |

|

|

Min |

0.33 |

0.49 |

|||||

|

Max |

1 |

1 |

|||||

|

Health concern in the future |

Med |

0.50 |

0.75 |

0.25 |

60.00 |

0.484 |

|

|

Min |

0.25 |

0.25 |

|||||

|

Max |

1 |

1 |

|||||

Med: Median. Min: Minimum. Max: Maximum. APR: Abdominoperineal resection.

LAR: Low anterior resection. ULAR: Ultra-low anterior resection.

DISCUSSION

Colorectal cancer is a common cancer with high mortality rates. Surgery remains a fundamental part of CRC treatment. The management involves multimodal therapy

with low recurrence rates; however, these treatments impact the patient's quality of life (10,25).

This study compares the quality of life of CRC patients treated with APR versus sphincter-preserving resections: LAR and ULAR.

CRC ranks third in terms of incidence, with a reported incidence of 10.9% in males and 9.5% in females (1,26).

This study found a slight predominance of females, accounting for 54% of the patients.

Patients undergoing APR in this study had a mean quality of life score of 73.72 (good quality of life). They reported urinary and gastrointestinal symptoms, as

well as body perception and sexuality, without interference in their quality of life. Some studies have reported better quality of life in patients undergoing APR,

while others have concluded that there are no differences in quality of life based on the type of intervention (27,28).

Patients undergoing LAR/ULAR in this study had a score of 56.22 (poor quality of life). They reported that their sexual health affected their quality of life, while

urinary, gastrointestinal, and body perception symptoms did not interfere with it. Patients undergoing LAR/ULAR did not report urinary symptoms, sexual problems, or

body perception issues (27).

APR interventions are more frequently associated with postoperative complications, perianal infections, and delayed wound healing (29).

A higher local recurrence rate and a 5-year survival rate were observed in APR. The one-year comparison of quality of life in patients with APR versus LAR/ULAR was

lower in APR (30).

Studies have concluded that there are no differences in age, sex, education, cancer duration, and stage among patients undergoing APR compared to LAR/ULAR

(31,32).

Both procedures were evaluated to improve psychological and emotional well-being, although patients undergoing LAR/ULAR stood out for their notable progress

(33).

CONCLUSION

There is no significant difference in the quality of life of CRC patients operated on with APR, LAR, and ULAR (conservative and non-conservative approaches).

Patient counseling is recommended before performing APR or LAR/ULAR (34), as the decision is based on the information provided by the patient and whether they are willing to tolerate more intestinal symptoms to avoid a permanent colostomy (35).

Authorship contribution statement:

The authors participated in the elaboration of the idea, project design, data collection, interpretation, analysis of results

and manuscript preparation of this research work.

Funding:

Self-funded.

Conflict of interest statement:

The authors stated that they had no conflict of interest.

Received:

N/A

Approved:

N/A

Correspondence:

Arturo García Galicia.

Address:

Calle 2 Norte #2004. Colonia Centro.

Phone number:

(222) 1945360

E-mail:

neurogarciagalicia@yahoo.com

Article published by the Journal of the faculty of Human Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University. It is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creatvie Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0/), that allows non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. For commercial use, please contact revista.medicina@urp.edu.pe.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES