REVIEW ARTICLE

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2024 - Universidad Ricardo Palma10.25176/RFMH.v24i1.6333

NON-FATAL STRANGULATION/SUFFOCATION IN CONTEXT OF GENDER VIOLENCE: MEDICOLEGAL ASPECTS AND IMPLICATIONS IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

ESTRANGULACIÓN/SOFOCACIÓN NO FATAL EN EL CONTEXTO DE VIOLENCIA DE GÉNERO: ASPECTOS MÉDICO-LEGALES E IMPLICANCIAS PARA LA PRÁCTICA CLÍNICA

Mónica Núñez Garrido

1,a

1,a

Sergio Herrera Umanzor

2,3,b,c

2,3,b,c

1 Department of Medical Specialties, Universidad de La Frontera. Temuco, Chile

2 Universita Degli Studi di Verona, Italia.

3 Department of Pathological Anatomy, Universidad de La Frontera. Temuco, Chile.

a Surgeon

b Pathological Anatomist

c Master in Science Medico Forensi

ABSTRACT

Despite the numerous efforts of the international community to eradicate all forms of violence against

women, this problem is far from being resolved. According to the UN, one in three women has suffered

physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner, sexual violence outside the couple, or both at

least once in their life. Addressing this problem as a social health need of population groups allows an

approach to gender violence as a collective health problem.

At the level of physical violence, strangulation/suffocation has been identified as one of the most

lethal forms of domestic violence and sexual assault. Victims of domestic violence who have been choked

or strangled are 7.5 times more likely to be killed by their partner. A victim of

strangulation/suffocation can lose consciousness in seconds or die within minutes, days or weeks after

the attack, as well as suffer permanent brain damage or disability or emotional trauma.

Recently, legal changes have been generated in the configuration of this crime, the penalties have

increased in United Kingdom, the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

The current non-systematic narrative review of literature sought to explore updated medico-legal aspects

of non-fatal strangulation/suffocation in the context of gender violence, and are highlightedrelevant

implications for clinical practice.

Keywords: Asphyxia, domestic violence, intimate partner violence, forensic medicine, physical

examination (Source: MeSH).

RESUMEN

A pesar de los numerosos esfuerzos de la comunidad internacional en pos de erradicar todas las formas de

violencia contra las mujeres, esta problemática se encuentra lejos de ser resuelta. Según la ONU, una de

cada tres mujeres ha sufrido violencia física o sexual por parte de la pareja, violencia sexual fuera de

la pareja, o de ambas, al menos una vez en su vida. El abordaje de esta problemática, en tanto necesidad

social de salud de grupos poblacionales, permite una aproximación a la violencia de género como un

problema de salud colectiva.

En el plano de la violencia física, la estrangulación/sofocación ha sido identificada como una de las

formas más letales de violencia doméstica y agresión sexual; se ha reportado que una víctima que es

estrangulada una primera vez tiene 7,5 más probabilidades de ser asesinada posteriormente por el mismo

abusador. Una víctima de estrangulación/sofocación puede perder la conciencia en segundos o morir en

minutos, días o semanas después del ataque o sufrir daño cerebral permanente o invalidez, además del

trauma emocional.

Recientemente, se han generado cambios legales en la configuración de este delito; las penas han

aumentado en el Reino Unido, Estados Unidos, Australia y Nueva Zelandia.

El propósito de esta revisión de literatura de tipo narrativo, no sistemática, está orientada a

presentar aspectos médico-legales actualizados de la estrangulación/sofocación no fatal en el contexto

de la violencia de género, y se resaltan aquellas implicancias relevantes para la práctica clínica.

Palabras clave: Asfixia, violencia doméstica, violencia de pareja, medicina forense, examen

físico (Fuente: DeCS-BIREME)

INTRODUCTION

Gender equity, understood as the balanced recognition and valuation of the potential of women and men,

the distribution of power between both, and its application, establishes the recognition of different

realities, interests, and needs of women and men for the formulation of plans, programs, and

interventions that aim at a differentiated and efficient impact, recognizing and working on social

inequities. Despite numerous efforts by the international community to eradicate all forms of violence

against women, this problem is far from being solved. According to the UN, it is estimated that one in

three women has suffered physical or sexual violence by a partner, sexual violence outside the

partnership, or both, at least once in their life (1).

Violence against women, in the family context, can have physical, psychological, economic, and sexual

aspects (2). In the area of physical violence, strangulation has been

identified as one of the most

lethal forms of domestic violence and sexual aggression and has become one of the most accurate

predictors of subsequent homicide in victims of intrafamily violence (3, 4).

Legal medical textbooks, usually, focus on the phenomenon of asphyxiation as a finding in necropsy,

however, gender violence contexts hide many non-fatal cases that do not appear in official figures and

that may eventually turn up at health centers, where staff should be able to detect and, eventually,

formalize the corresponding complaint. Moreover, a particular group of victims may present even serious

complications including the possibility of a deferred death (5, 6).

Internationally, the so-called non-fatal strangulation/suffocation (without resulting in death) is

configured as any case in which a person intentionally strangles or suffocates another, including cases

of intrafamily violence (7 - 9). The legal approach to

these types of aggressions led to changes in laws

and associated penalties in the United Kingdom, United States, Australia, and New Zealand; defining it

as a crime and increasing the severity of sanctions, including prison sentences (7).

The purpose of this narrative, non-systematic literature review is to present updated medico-legal

aspects of non-fatal strangulation/suffocation in the context of gender violence; highlighting those

implications relevant for clinical practice.

Medico-Legal Aspects

The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women was approved without a vote by the United

Nations General Assembly with Resolution 48/104 on December 20, 1993, in which it was established as a

violation of their rights and a factor of severity that affects health (1).

WHO estimates from 2018

reported that the lifetime prevalence of violence in women worldwide is 30% (1).

Among the forms of physical violence against women, strangulation and suffocation present a high risk of

lethality, and are associated with other forms of aggression (10). It is

described as a type of abuse

associated with the pursuit of control and intimidation of the victim, over homicidal intent (3, 6, 11, 12), but,

despite its intimidating nature, exposes victims 7.5 times more than the rest of the

population to be murdered (3).

Considering the varied meanings of the term suffocation, for the purposes of this review, we have

considered it as mechanical asphyxiation by occlusion of the respiratory orifices (13 - 15), which in the

case of the law in the United Kingdom extends to "any action that affects the ability to breathe and is

considered assault" towards the victim (16). In contrast, strangulation

corresponds to mechanical

asphyxiation produced by compression of the neck by an active force exerted by hands, ligature, body

parts, or another rigid object, which makes it difficult to adequately oxygenate the brain, mainly due

to vascular occlusion (3, 13).

Plattner et al., in a retrospective case study, specifies the distribution of strangulation victims

according to their type and demographic aspects. Regarding the type of strangulation, 82% of cases

corresponded to manual strangulation, 16% by ligature, and 2% a combination of the previous ones. 97% of

the victims were adults, predominantly between the ages of 20 and 30, and 3%, children. 85% of the

victims are female, and 15%, male. All the male victims in this series were attacked by men. Of the

women, only in two cases was a female aggressor suspected (9).

The intensity of the sequelae or the death of the victim would be directly proportional to the time of

exposure to oxygen deprivation and to the active force exerted, although these premises are based on

case studies in fatal hangings captured by video (3, 17).

One of these reviews is carried out by the

Working Group on Human Asphyxia, in which it was observed that people lost consciousness within the

first 10 seconds of vascular occlusion, the appearance of petechiae occurred within 30 seconds of venous

occlusion, and they maintained movements and respiratory noises for around two minutes (3), results

similar to the study by Kabat in 1943 (18). Even in people who have been

released alive from the

occluding element (in strangulation or in hanging), there may be a deferred death due to anoxic

encephalopathy secondary to reduced cerebral blood flow (5, 17).

While research on gender violence in the last 30 years has favored advances in the typification of

crimes against women, only a few countries have specific laws regarding non-fatal

strangulation/suffocation. One of the initial major obstacles was to demonstrate its occurrence and to

socialize the extreme form of violence it represents. Multiple initiatives with victim participation,

such as "we can't consent to this" (a UK group whose volunteers seek to raise awareness of sexual

violence) and the "Centre for Women's Justice" (a UK organization made up of lawyers and academics

specializing in violence against women), have promoted studies, systematic reviews, and even legal

advice. Their work has made it possible to visualize the neurophysiological impact of aggression on

survivors of non-fatal strangulation episodes (19).

Currently, this form of aggression is criminalized in countries such as the United States (20),

Australia, and the United Kingdom (16). In the United Kingdom, the new

Domestic Violence, Crime and

Victims Act was enacted on June 7, 2022, which in its sections 75 A and 75 B typifies the crime of

non-fatal strangulation/suffocation (7, 16, 21), which is not limited to the results of the acts, but to

the action itself of cervical compression or occlusion of respiratory orifices. With this, it is not

required that the victim loses consciousness or has accentuated secondary damages for the crime to be

configured (7, 16). Along with its new typification,

sanctions were increased and differentiated from

what was previously established in the context of bodily injuries. The new penalties range from one to

five years of effective imprisonment, and compare with the previous payment of fines (16, 21). The

population affected by this law is not only citizens within the territorial limits, but also people who

carry the nationality and commit the criminal act abroad, as well as foreign residents and foreigners in

transit within the territorial limits (7, 16, 21). After its enactment, in 2022, the first detainee was

on June 10, 2022 (8) and one of the first sentenced to prison was on October

27, 2022, with a sentence

of 18 months. For the application of this legislative change, the Crown Prosecution Service developed

guidelines for its lawyers to make proper use of these legal changes and how to direct the investigation

(7, 22), similar to the guide issued by the California

District Attorneys Association (CDAA). In the

case of training and technical assistance for professionals involved in contexts of intrafamily

violence, there are institutions such as the Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention (20) and The

Family Justice Center Alliance, both from California, which, in addition to providing legal assistance

to victims, are also research and training centers for professionals in both the legal and health

fields. One achievement of these initiatives was that, step by step, the different states of the North

American country ended up typifying non-fatal strangulation/suffocation as a serious crime in itself and

not as a minor offense or misdemeanor (9, 23); Ohio was

the last to include it in April 2023.

In Chilean medico-legal practice, non-fatal strangulation/suffocation is not specifically typified, but

is included within the crimes of bodily injury. Under this concept, there may be an increase in its

legal qualification, if it is carried out in the context of intrafamily violence (24). Injuries are

classified according to their severity, so the crime of injuries considers sentences that will depend on

the result of the attack from one person to another, from a misdemeanor in the case of minor injuries to

crimes with penalties of 10 years in case of mutilation or permanent damage. However, when injuries

occur in the context of gender violence or intrafamily violence, it would constitute an aggravating

factor, which implies risking a minimum penalty of 61 days of imprisonment, regardless of the magnitude

of the injuries. The penalty could reach up to 15 years of imprisonment for the aggravating factor of

injuries in the context of intrafamily violence. The scope of the norm is limited to crimes committed in

the territory of the Republic by inhabitants and foreigners (24).

Implications for Clinical Practice

Healthcare professionals may encounter patients who have suffered non-fatal strangulation/suffocation in

various scenarios of their practice, including emergency services, whether because the victim

spontaneously relates it, as a reason for consultation, or through the detection of suggestive physical

signs. This medico-legal entity requires active suspicion to identify patients in danger, especially

because cases without obvious external injuries can be treated (6).

History and Physical Examination

Only 5% of strangulation victims seek medical attention within the first 48 hours after the assault; it

is interpreted that they would seek help due to the appearance of some symptom (4). When medical

assistance is sought, symptoms such as neck pain (25), hoarseness (11, 26), dysphagia (3, 11, 19),

headache (11), breathing difficulties (3, 11, 25, 26), dizziness (3, 19), tinnitus (19), and

vision

changes (19, 26) are reported. It has also been described

that patients can consult showing great

emotional distress and anguish, which can cause medical teams to underestimate the reported aggression,

biasing the consultation and attributing symptoms to a state of intoxication, hyperexcitation, and even

substance abuse (5, 6, 27).

In traditional forensic pathology texts, it is common to find a section devoted to the so-called

asphyxia syndrome and its possible causes, which are multiple, and whose classically described signs are

petechiae, visceral congestion, pulmonary edema, cyanosis, and the controversial fluidity of the blood

(13 - 15). Likewise, these texts usually address

strangulation and suffocation separately and mention the

inconsistent presence of contusive lesions (ecchymosis, erosions, and excoriations) in a ligature or

finger pattern on the neck and facial region. It should be noted that these classic signs are

nonspecific by themselves for the diagnosis of the cause of asphyxia, so a correlation must be

established with the study of the scene and the remaining background of the investigation (3, 13, 17),

in pursuit of making plausible diagnoses.

More specifically, and with special attention to non-fatal strangulation/suffocation, there are articles

highlighting that 50% of the victims did not present visible cervical injuries at the time of

examination (5, 6, 27). In another

series, it is reported that although 75% of the evaluated people were

examined during the first 24 hours post-assault (11), 35% of them presented

injuries categorized as

mild. Comparing the injuries described in reports of both surviving and deceased patients, it is

described that in strangulation/suffocation, it is possible to recognize contusive injuries of similar

characteristics and distribution, which may be added to cutaneous, conjunctival, and/or oropharyngeal

mucosa petechiae (3, 5, 6, 11,

25, 26). Facial and/or cervical edema has also been

described (6, 25, 26). However, the

physical examination may not present visible injuries because it clinically occurred

with signs that disappear quickly, such as erythema or discrete edema (28).

Other findings described in

the physical examination are contusions (ecchymosis, erosions, and wounds of the skin and lip mucosa,

epistaxis, fracture of the hyoid and laryngeal structures, hoarse voice, nausea and vomiting, memory

loss, consciousness compromise, seizures, incontinence of sphincters, facial paralysis or of

extremities, swallowing disorder, tremor, hemianopsia, ptosis, ataxia, coma, or dissection of the

carotid arteries (5, 6, 11, 19, 25, 26, 28).

Complications that occur within the first 48 hours after the assault include aspiration pneumonia,

laryngeal edema, pulmonary edema, ischemic stroke, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and death (5, 6, 17, 25, 28).

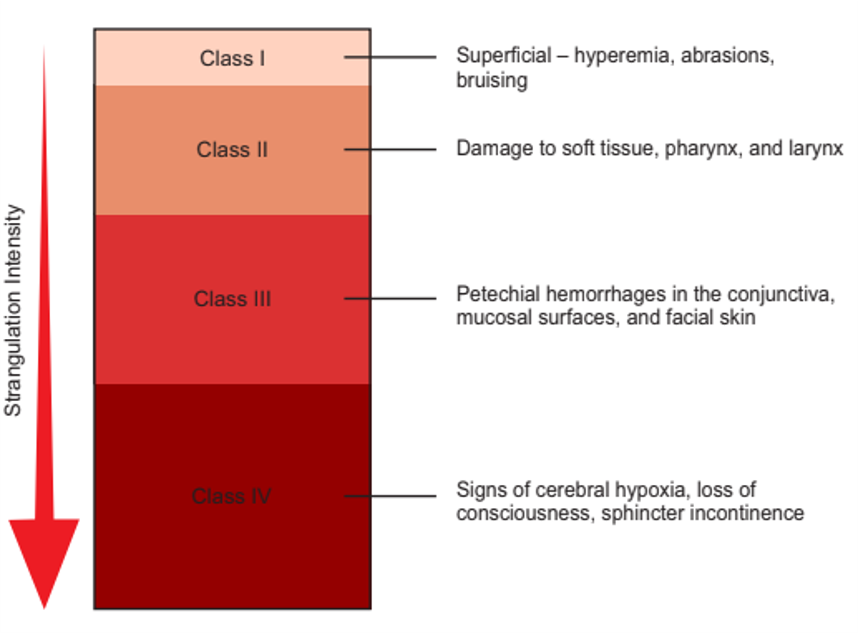

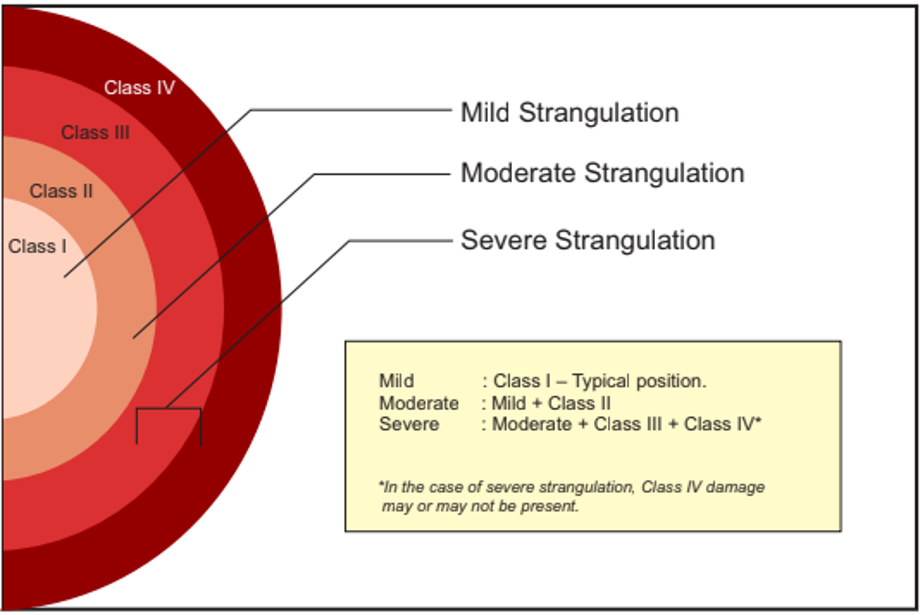

Plattner et al. propose the categorization of non-fatal strangulation and consider the severity and

systematization of physical examination findings, on the condition that the complete medico-legal

examination of the victim is carried out up to two days after the incident (figures 1 and 2) (25).

Own elaboration based on the systematization proposed by Plattner et al. (25).

Own elaboration based on the systematization proposed by Plattner et al. (25).

Additional Studies

Regarding additional studies, the reviewed publications suggest their implementation in symptomatic

patients for the detection of injuries requiring specialty treatment:

Cervical radiography for the detection of fractures (5, 17, 29).

Nasofibro-laryngoscopy to visualize petechiae of the laryngeal mucosa (5, 17, 29).

Computed tomography of the brain (5) and/or neck (3).

Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck (5, 26) and/or

brain (26).

Carotid or vertebral artery angiography by computed tomography (CT Angio): described as the standard of

reference for the evaluation of blood vessels (26, 29).

Carotid or vertebral artery angiography by magnetic resonance imaging (MRA) (29).

Management

Regarding approach and follow-up, it is recommended as good practice to keep patients under observation

for a period of time, not always specified, mainly due to the possibility of developing delayed

complications such as cervical or laryngeal edema, due to their life-threatening risk (5, 17, 26, 28, 30).

Considering the heterogeneous symptoms and signs, the possibility of immediate complications, and their

potential rapid evolution, different reviews suggest that a detailed evaluation and documentation of

external and internal injuries be carried out in cases of strangulation/suffocation, for a better

understanding by the justice prosecuting bodies regarding the real magnitude of the aggression (3, 11).

In this regard, the Faculty of Legal and Forensic Medicine of the Royal College of Physicians has issued

at least two publications on the subject; also, it is mentioned to consider the evaluation of the

patient by a specialist doctor in the presence of loss of consciousness, incontinence of sphincters,

respiratory difficulty with decreased oxygen saturation, difficulty or inability to speak, presence of

extensive ecchymosis, or subcutaneous cervical emphysema (6, 28). Additionally, it is recommended that,

in suspected cases, along with the pertinent medical care, a clinical record that includes key or

relevant points is made, which consider:

Complete record on the care sheet with description of positive and negative findings (27).

Photographs of the neck (anterior, posterior, and lateral) of the initial external injuries, and their

evolution if necessary, especially due to the risk of not being able to be verified in the following

days (6).

Performed imaging studies.

Consider the collection of evidence, such as subungual content (6).

It should be noted that health records, such as the medical record and/or emergency care forms, are

legally relevant documents when it comes to investigating crimes that threaten the physical integrity

and health of people and, sometimes, constitute the only evidence for judicial investigation (3).

CONCLUSIONS

In the field of violence against women, which includes intrafamily and sexual violence, non-fatal

strangulation/suffocation is a medico-legal entity that has gradually been recognized as a crime in the

international context, given its prevalence and importance as a predictor of homicide. Efforts by

academic, medical, judicial, and citizen bodies have enabled its visibility and socialization.

Healthcare personnel must maintain an expectant attitude in the context of gender violence, both

oriented towards suspicion and the search for injuries that, at first glance, might go unnoticed, since,

depending on the distribution and severity of the injuries associated with an episode of

strangulation/suffocation, scenarios can range from the absence of visible injuries to death. In the

spectrum of clinical presentations, a victim of strangulation/suffocation can lose consciousness in

seconds or die in minutes, days, or weeks after the assault. This is due to associated injuries,

complications of the respiratory system, or brain damage; to which is added the emotional impact on the

victim.

Consequently, good practice involves active suspicion, possible hospitalization, adequate clinical

records, and the performance of pertinent additional studies, as well as the presentation of a complaint

to the relevant judicial authorities, always incorporating informed consent and confidentiality

safeguards.

Authorship contributions:

MNG participated in the conceptualization, research, methodology, resources, and writing of

the original draft. SHU participated in the conceptualization, methodology, writing and

review of the draft.

Financing:

Self-financed

Declaration of conflict of interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Recevied:

January 22, 2024

Approved:

February 8, 2024

Correspondence author:

Mónica Núñez Garrido

Address:

Manuel Bulnes 369, Temuco, Araucania Region, Chile.

Phone:

(+56) 991616671

E-mail:

monica.nunez.g@gmail.com

Article published by the Journal of the faculty of Human Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University. It is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creatvie Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0/), that allows non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. For commercial use, please contact revista.medicina@urp.edu.pe.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES