ORIGINAL ARTICLE

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2024 - Universidad Ricardo Palma10.25176/RFMH.v24i3.6488

CERVICAL UTERINE CANCER IN THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC IN RURAL COMMUNITIES OF AYACUCHO

CÁNCER CERVICOUTERINO EN EL CONTEXTO DE LA PANDEMIA DE COVID-19 EN COMUNIDADES RURALES DE AYACUCHO

Lucy Orellana de Piscoya

1,a

1,a

1 Universidad Nacional San Cristóbal de Huamanga, Ayacucho. Lima, Perú.

a PHd Public health.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, vulnerable rural women faced significant challenges.

Objective: To explore the situation of cervical cancer during the pandemic from an intercultural

perspective among rural women in Ayacucho in 2021.

Methodology: Mixed-method research with a concurrent triangulation design. Sample: Healthcare

providers and rural women. Purposeful and reasoned sampling. Techniques: Surveys, in-depth interviews.

Data analysis: Data systematization using Excel, SPSS for quantitative data, and Atlas.ti for

qualitative data. Level of validity and confidence: triangulation.

Results: Information from surveys and interviews was contrasted, revealing that the problem may

have alternative solutions within the knowledge of the same communities.

Conclusion: Women reported lack of awareness, insufficient information in the Quechua language,

and undervaluation of their traditional knowledge. Fear and contagion concerns prevented them from

seeking healthcare services. Services were reduced, redirected, or discontinued, often due to budget

constraints.

Keywords: Uterine cancer – Pandemic – Rural Females

RESUMEN

Introducción: Debido a la pandemia de COVID-19, las mujeres rurales en situación de

vulnerabilidad enfrentaron desafíos importantes.

Objetivo: Explorar la situación del cáncer cervicouterino durante la pandemia desde una

perspectiva intercultural entre las mujeres rurales de Ayacucho en el año 2021.

Metodología: Investigación de métodos mixtos con un diseño de triangulación concurrente. Muestra:

Proveedores de atención médica y mujeres rurales. Muestreo intencional y razonado. Técnicas: Encuestas,

entrevistas en profundidad. Análisis de datos: Sistematización de datos utilizando Excel, SPSS para

datos cuantitativos y Atlas.ti para datos cualitativos. Nivel de validez y confianza: triangulación.

Resultados: El contraste de la información de encuestas y entrevistas reveló que el problema

podría tener soluciones alternativas dentro del conocimiento de las mismas comunidades.

Conclusiones: Las mujeres reportaron falta de conciencia, información insuficiente en quechua y

subvaloración de sus conocimientos tradicionales. El miedo y la preocupación por el contagio las

disuadieron de buscar servicios de salud. Los servicios se redujeron, redireccionaron o descontinuaron,

a menudo debido a limitaciones presupuestarias.

Palabras clave: Cáncer cérvico-uterino - Pandemia - Mujeres rurales

INTRODUCTION

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the health system experienced a crisis that impacted society, especially rural women from vulnerable sectors (1,2). Social actors and the roles they play are shaped and interact based on the access and equity available. From health services during the COVID-19 health emergency, the scarcity of material and human resources was evident, denoting inequality; As a consequence, the care of cancer patients was neglected, resulting in an underlying scenario with a high death rate (3).

In this way, the demand in primary care prioritized COVID-19 cases and left aside other diseases such as cancer (4). This is how the relationship between the various elements of the problem becomes important and contextualizes the reality where the right to health in the midst of a pandemic was critically affected.

Research has evaluated the adaptation of cancer protocols in the pandemic and has analyzed how it affected patients in different phases (5). For example, for the management of bladder cancer, treatment protocols adjusted to the oncological risk and the phase of the pandemic were carried out (6); algorithms were also identified for the management of kidney cancer according to the oncological stage (7). It should be noted that cervical cancer is a global disease and its prevalence increased during 2020, at the height of the pandemic; Furthermore, it was found that in Peru the mortality rate from this type of cancer ranks fourth (8). For this reason, and for the experience of previous pandemics, it was suggested to act quickly and study them (9).

The present study sought to explore the situation of cervical cancer in rural women during the COVID-19 pandemic seen from an intercultural approach. It is necessary to carry out studies on women in the rural sector that contribute to the update so that policies consider the gender, equity, and ethnicity approaches within a human rights framework, with the purpose of promoting equality.

METHODOLOGY

Design and Study Area

This research employed a mixed-methods approach, grounded in a concurrent triangulation design. The

study was conducted in Luyanta Hualpa, Socos, in Lima – Perú, focusing on both qualitative and

quantitative data collection methods. Semi-structured interviews and surveys were used to explore the

target population, with data collection and analysis performed simultaneously (10).

Population and Sample

The sample consisted of 12 rural women and 4 healthcare providers from the study area. A

non-probabilistic convenience sampling method was used for the quantitative analysis, while a purposive

sampling strategy was applied for the qualitative analysis (10).

Variables and Instruments

The research utilized a variety of instruments for data collection, including surveys and

semi-structured interview guides. Quantitative data were collected to capture demographic and service

utilization information, while qualitative data were aimed at understanding personal experiences and

perceptions related to cervical cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Procedures

For the quantitative component, data were processed using the SPSS statistical software, with the

analysis remaining descriptive to explore the sample characteristics. The qualitative analysis involved

systematic procedures such as data organization, iterative reading, coding, and the use of traditional

techniques alongside Atlas.ti software. The findings from both qualitative and quantitative analyses

were then triangulated to enhance the study's reliability and provide a comprehensive understanding of

the research problem.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics in SPSS to summarize the sample

characteristics. Qualitative data were analyzed through coding and thematic analysis using Atlas.ti. The

concurrent triangulation method was employed to integrate and compare the results from both data sets,

ensuring a robust and nuanced interpretation of the findings.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained prior to the commencement of the study, and informed consent was obtained

from all participants. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the research process,

and the study adhered to ethical standards in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

RESULTS

Quantitative results

Interviews were conducted with a total of 16 participants: 4 were health services workers and 12 were

women living in rural areas of Ayacucho. Of these women, 6 were from Luyanta, 3 from Huambalpa, 2 from

Vilcas Huamán and 1 from Socos. Regarding marital status, 3 lived with their partners and the others

were married. Regarding education, 2 women had no education, 4 had incomplete primary school and 6 had

incomplete secondary school. The majority of the women surveyed are dedicated to household chores,

except for two who are businessmen. The participants stated that they had children, one has 7 children,

2 have 3 children, another 2 have 5 children, 3 have 6 children and 4 have 4 children. They all have

Quechua as their native language.

| Sociodemographic variable | F | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age ranges | ||

| 25 – 62 years | 12 | 100% |

| Origin | ||

| Huambalpa | 3 | 25% |

| Vilcas Huamán | 2 | 16.67% |

| Socos | 1 | 8.33% |

| Luyanta | 6 | 50% |

| Civil status | ||

| Cohabitant | 3 | 25% |

| Married | 9 | 75% |

| Occupation | ||

| Housewife | 10 | 83.33% |

| Dealer | 2 | 16.67% |

| Number of children | ||

| 7 children | 1 | 8.33% |

| 3 children | 2 | 16.67% |

| 5 children | 2 | 16.67% |

| 6 children | 3 | 25% |

| 4 children | 4 | 33.33% |

| Language | ||

| Quechua | 12 | 100% |

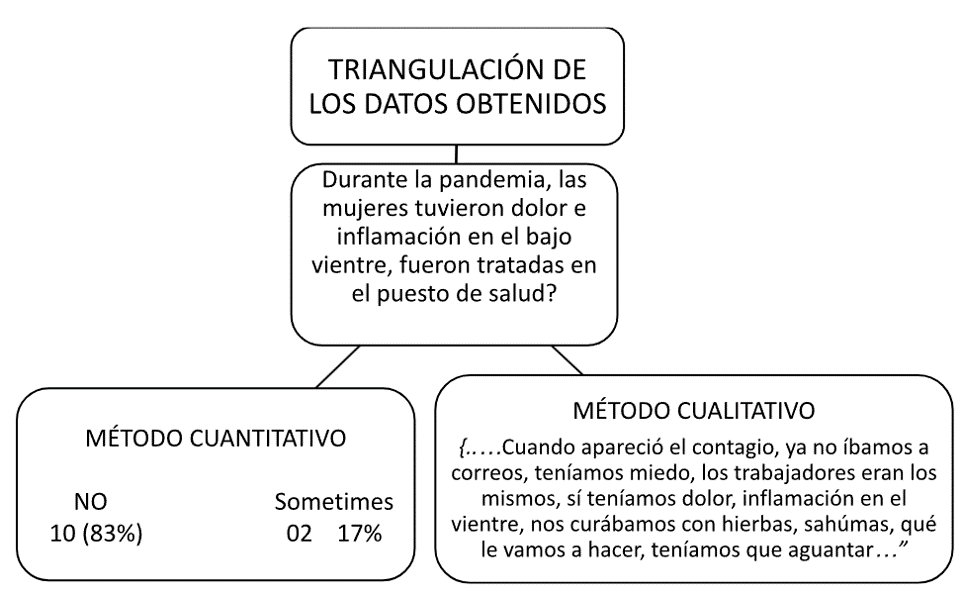

Table 2 highlights that during the pandemic in rural communities, 83% of women who had inflammation did not receive medical treatment, 67% did not receive information about Pap smears, and 83% could not access services adequately because Quechua was not spoken.

| Description of questions. | SI | NO | A VECES | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During the pandemic, did women have pain and inflammation in the lower abdomen, were they treated at the health post? | - | 10 | 83% | 02 | 17% | |

| Have the women in your community heard talks and information about the Pap smear from the health post staff during the pandemic? | - | 08 | 67% | 04 | 33% | |

| When you go to the health post, do they serve you well, speaking Quechua, do they respect your customs? | - | 10 | 83% | 02 | 17% | |

| During the pandemic, did you go to the health post or were you afraid of contagion? | - | 11 | 92% | 01 | 8% | |

| Do you cure yourself with herbs or other home remedies when you have something wrong with your body or womb? | 08 | 67% | - | 04 | 33% | |

| During the pandemic, did the health post staff visit you at home? | - | 11 | 92% | 01 | 8% | |

| Did you have a mask to go to the health post? | - | 02 | 17% | 10 | 83% | |

| During the pandemic, were you looking for the healer, herbalist to cure you of some illness in your parts or pain in your womb? | 08 | 67% | 04 | 33% | ||

Regarding the 4 surveyed participants who work in the health sector, as can be seen in Table 3, they affirm that the offer of health services that offer prevention of cervical cancer to rural women in Ayacucho does not maintain a good management; likewise, 3 of those surveyed were suspended during the health emergency and 4 had limitations due to lack of PPE. Regarding attendance, the 4 collaborators reported that women did not attend due to fear of contagion and due to the high demand for care and priority in COVID-19 cases.

| Cervical Uterine Cancer Screening Program Services in rural areas in Ayacucho, during the COVID-19 pandemic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ítems | YES | NO | SOMETIMES | |||

| They had normality in their management | 0% | 04 | 100% | |||

| They were suspended | 03 | 75% | 01 | 25% | ||

| They were limited due to lack of PPE | 04 | 100% | ||||

| Women did not attend out of fear | 04 | 100% | ||||

| Prioritization of services due to COVID-19 | 04 | 100% | ||||

| Training for health providers to face the pandemic | 01 | 75% | 03 | 75% | ||

Data obtained by survey

Table 04 describes the response capacity of health services in rural areas of Ayacucho for the prevention of cervical cancer in the COVID-19 pandemic, where 100% of health providers report that it was neither timely nor safe, and 02 (50%) reported that they moved to a second order, prioritizing services and servers towards the care of patients due to COVID-19. Likewise, 100% reported that the first level of care was paralyzed and there was saturation of health services due to cases of COVID-19, community participation was very weak or non-existent, mental health problems were observed in health providers, the absence of an adequate communication strategy was also evident, and interventions in sexual and reproductive health were postponed indefinitely.

| The response capacity of health services for the prevention of cervical cancer during the COVID 19 pandemic was: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ítems | YES | NO | SOMETIMES | |||

| Timely and appropriate | 04 | 100% | ||||

| Step to a second order | 02 | 50% | 02 | 50% | ||

| They paralyzed attention at the first level | 04 | 100% | ||||

| Saturation of health services due to COVID-19 cases | 04 | 100% | ||||

| Weak community participation | 04 | 100% | ||||

| Lack of an adequate communication strategy | 04 | 100% | ||||

Data obtained by survey

In conclusion, 100% of the health services were neither timely nor adequate, and 50% reported that they went to a second order, just as there was saturation in the health services, and regarding community participation, 100%. I indicate that participation was weak and there was no adequate communication strategy.

Resultados cualitativos

Qualitative results Below are verbatim excerpts from the interviews that the health personnel who participated in the Sexual Reproductive Health services/Cervical Uterine Cancer Screening Programs during the COVID-19 pandemic provided. They refer in their entirety that health services during the pandemic period were unsafe and were classified as places of risk of contamination, interviewee A comments that :

[...] Nobody knew about the problems that health workers had to face in the face of COVID-19, they did not know what to do [...] there was a lot of fear, trepidation, all the users in the population for us were carriers of the virus, they were difficult situations and In this whole problem, everything that was not COVID-19 was not attended to […] but it was not that we did not want to attend to it, but rather we were afraid, people were dying, dying was very painful […] (Interviewee A, health personnel)

Thus, it is also observed that one of the strongest reasons for not attending was that all services were prioritized to provide care for COVID-19 cases and that the situation regarding care became complex.

[…] In reality, those of us who are in charge of the population, such as the posts and health centers, are the ones who had to face the entire problem of the COVID-19 pandemic, all staff were obliged to provide care to the patients. infected, and we were not even trained in that, but we were even forced to transport the dead, and in those circumstances no one gave importance to the other services, some days we closed because there were no conditions […] (Interviewee B, health personnel)

Health workers emphasize that the pandemic generated obstacles in the care of cervical cancer, linked to structural problems in the health system. Although primary care is considered a priority, it could not be effectively implemented in practice due to lack of training and slow implementation of protocols, aggravated by the presence of COVID-19. On the other hand, interviews with rural women highlight their active participation in their communities.

[…] When the contagion appeared, we no longer went to the post office, we were afraid, the workers were the same, we did have pain, inflammation in the womb, we cured ourselves with herbs, sahúmas, what can we do, we had to endure […] (Rural woman A)

In this category, the rural women in the study clearly report the reasons why they did not access care in health services, especially for screening for cervical cancer, or to prevent ailments related to this disease, or some who are already in treatment they could not continue.

[…] I no longer went to the post, there was COVID-19 contagion, it was closed, it was mandatory to wear a face mask, they only spoke to us from afar, they didn't listen and we didn't understand anything, they didn't want to get close to us... The community had a misfortune, our neighbor died bleeding from all parts of her body. She was already over 60 years old, now we are just being told that it was probably due to uterine cancer... so it was very sad, we women did not have any attention for our illnesses [...] (Rural woman B)

Health personnel, poorly informed about COVID-19, treated women with inadequate practices, excessive distance, masks that made communication difficult, and language barriers. Some medical services closed, leaving rural women feeling abandoned and helpless due to the pandemic.

[…]before the infections started, I had a bloody wound treated by the obstetrician, I went every Monday, but after that they didn't open the door anymore, I was afraid to even get close to them, so I gave up, until now I haven't had it treated because they have also changed the obstetrician, she was very good […] (Rural woman C)

The pandemic revealed that the health sector was not prepared to address the sexual and reproductive health needs of women. Fear and lack of preparation led to neglect, and women were one of the most affected populations, not only by COVID-19, but also by the consequences on the delivery of health services.

[…] at that time of contagion, my daughter, who is married, told me that she had a lot of pain when she was intimate with her husband, it was getting worse and worse, she even bled, but I couldn't do anything, there was no attention, not even in particular [… ] (Rural woman D)

The COVID-19 pandemic caused very significant transformations in the organization of health services, especially in rural areas, generating greater risk in vulnerable populations such as rural women.

[…] we almost don't know anything about women's cancer, because they don't do the talks in Quechua, so maybe we can understand better, when they talk in Spanish, we only understand some things, but they also talk in the talk as if without anything from the parties of women […] that is not right, we are ashamed to look and listen when they talk to us like that […] (Rural woman E)

In this culture, there is popular language about cervical cancer.

[…] […] in the community we have other illnesses and sometimes they say cancer, but it can be alcanzo, pacha or worse still ccapiruzcca, at the post when they can no longer cure you they say cancer, and they give us remedies that sometimes clash, or they send you to File so they can cure you, and there is no money, how are we going to go [...] we understand that cancer has no cure, if it catches you you die, here we have seen several women die with cancer, when it is in the finals they can no longer stand the pain They scream, they cry and the entire community listens, they even throw him out of the hospital and he just waits to die […](Rural woman F)

[…] in our community there are still our healers and some midwives, they know well what plants they can take and also make cures so that the sick person will heal, but we all know if it is cancer, she will die, there are times that we invoke God to our apus who I took it away without suffering much, my neighbor's entire body swelled, she could no longer urinate and everything stayed in her body and she was like a balloon and the pain did not even allow the sheet or blanket to touch her, she suffered a lot […] (Rural woman G)

[…] they say that the virus that causes cancer has women who have several men, well, they are bad women, so how do they find the virus, what would my mother-in-law, my own husband, think […] it's sad because how many women perhaps don't get rid of it? that […] (Rural woman H)

Concurrency triangulation

Figure 01 presents the comparison of results obtained through mixed research. Regarding whether women with pain or inflammation in the lower abdomen during the pandemic were treated at the health post, it was found, through the surveys, that more than two thirds of the women did not receive care, while the interview provided testimonies that support this statement. One user mentioned that, due to fear of contagion, both they and health workers avoided going to the clinic and resorted to home remedies. The consistency between both results reinforces the idea that access to health services during the pandemic was difficult due to fear of contagion.

The data collected shows significant consistency: more than 80% of the people surveyed stated that they did not receive care at the health post. This finding is supported by the testimonies of those who mentioned that they stopped attending the health post due to fear.

It is essential to ensure that women receive adequate reproductive and sexual health care, as well as during pregnancy. The services that care for them should not be interrupted, avoiding their isolation from health facilities. It is necessary for health policies to have effective actions with strategies for pandemic contexts, especially those that last for long periods of time (11), in addition, the difficulty in accessing health services could translate into a complaint for the cases.

Figura 01: Triangulación de concurrencia entre resultados cuantitativos y cualitativos

Fuente: Elaboración propia.

DISCUSSION

It is clear that many women were not aware of the preventive measures to avoid cervical cancer. The information they require is basic, and they demand that it be provided in Quechua, their native language and that of their families. They insist on having their customs understood and taken into account when decisions are made. The findings underscore the need to strengthen information and education on women's sexual and reproductive health with an intercultural approach (12), which considers cultural norms and the efficacy of traditional medicine practices.

Furthermore, the failure to formulate effective strategies contradicts the objectives set by the World Health Assembly, which aims to combat and eradicate cervical cancer (13).

The testimonies highlight that these women are part of the Andean-Amazonian culture, where traditional knowledge, practices, customs, and beliefs about health persist. They recognize diseases that are treated using traditional medicine and utilize herbalism and other community-specific remedies. This demonstrates the social legitimacy and ongoing relevance of traditional medicine systems. They value the knowledge of Andean healers and actively seek their services (14).

In cases such as cervicitis, women report using natural methods for treatment, indicating that there is sometimes complementarity between traditional and Western medicine. These situations challenge the sociocultural analysis of health-disease processes (15), requiring mutual understanding to develop more effective health intervention strategies.

However, cultural factors also present challenges in the behavior of husbands, partners, and spouses, involving issues such as infidelity, insecurity, and distrust towards women. These behaviors reflect deep-seated stereotypes and low self-esteem, which often deter rural women from seeking healthcare services, particularly for genital examinations (16).

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the results suggest that cervical cancer was not optimally addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic due to various external and internal national factors. This exacerbated the underlying issues surrounding COVID-19 deaths. Nevertheless, rural areas have developed alternative strategies to cope with such scenarios. It would be beneficial for medical personnel to become more involved in addressing these issues to enhance the knowledge of this population.

It is crucial to acknowledge that cervical cancer remains a significant problem in Peru, with the highest number of victims among oncological diseases as of 2022. A significant proportion of cases are advanced and difficult to treat in individuals under 35 years old, comprising 54.1% of new cases of invasive cancer. Therefore, future research should focus on multidisciplinary studies to evaluate the effectiveness of medical programs in rural areas and determine if the prevalence of cervical cancer is decreasing.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: The author is the creator of the entire manuscript.

Funding: Funding for the preparation of this manuscript comes from the author's own

funds; there is no institutional participation or funding.

Received: March 23, 2024

Approved: June 13, 2024

Correspondence: Lucy Orellana de Piscoya

Address: 33, Av. Alfredo Benavides 5440, Santiago de Surco 15039

Phone: MISSING

Email: lucy.orellana@unsch.edu.pe

Article published by the Journal of the faculty of Human Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University. It is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creatvie Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), that allows non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. For commercial use, please contact revista.medicina@urp.edu.pe.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES