ORIGINAL ARTICLE

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2024 - Universidad Ricardo Palma10.25176/RFMH.v24i2.6505

MATERNAL COMPLICATIONS AND ADOLESCENT PREGNANCY IN LATIN AMERICA: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS

COMPLICACIONES MATERNAS Y EMBARAZO ADOLESCENTE EN AMÉRICA LATINA: REVISIÓN SISTEMÁTICA Y METAANÁLISIS

Maria A. Oviedo-Mendoza

1

1

María Angélica del Pilar Calsín Alvarado

1

1

Verónica E. Rubín-De-Celis

1

1

1 Facultad de Medicina Humana, Universidad Ricardo Palma, Lima-Perú.

ABSTRACT

Objective: To assess whether maternal complications are a risk in adolescent pregnancy in Latin

America and the Caribbean during the period 2012 to 2021.

Methods: A systematic search was carried out in 6 databases: PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science,

EMBase, LILACS and Scielo. The articles included were from Latin American countries and had any of the

following variables: preeclampsia, eclampsia, puerperal hemorrhage and puerperal sepsis published from

2012 to 2021 and comparing pregnant adolescents and adults. Articles that did not present separate

findings from Latin America and/or the Caribbean, that the full version was not available, and that were

focused on patients with a specific disease were excluded. For risk of bias, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

Case-Control Studies was used. The summary measure used was the Odds Ratio with a 95% confidence

interval for each study.

Results: 4 studies were included. The risk of preeclampsia in pregnant adolescents and postpartum

hemorrhage (OR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.74 – 0.99) were not evidenced (OR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.69 – 1.25). On the

other hand, the risk of eclampsia (OR = 2.43, 95% CI 1.29 – 4.58) in pregnant adolescents was shown, but

with high heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 76%).

Conclusions: A risk of eclampsia was evidenced in pregnant adolescents, but not in preeclampsia

nor postpartum hemorrhage. However, these results should be taken with caution.

Protocol record: CRD42021286725 (PROSPERO)

Keywords: pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, Adolescent, Pregnant Women. (Source:

MeSH NLM).

RESUMEN

Objetivo: Evaluar el riesgo de complicaciones maternas en el embarazo adolescente en

Latinoamérica y El Caribe durante el periodo 2012 al 2021.

Métodos: Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en 6 bases de datos: PubMed, SCOPUS, Web Of Science,

EMBase, LILACS y Scielo. Los artículos incluidos fueron procedentes de paises de Latinoamérica y

contaron con cualquiera de las siguientes variables: preeclampsia, eclampsia, hemorragia puerperal y

sepsis puerperal publicados desde el 2012 al 2021 y que compararan adolescentes y adultas embarazadas.

Se excluyeron artículos que no presentaron hallazgos separados de Latinoamérica y/o El Caribe, que no se

encontraban disponibles la versión completa y que estaban enfocados en pacientes con alguna enfermedad

en específico. Para el riesgo de sesgo se empleó la Escala de Newcasttle-Ottawa para estudios de casos y

controles. La medida de resumen empleada fue el Odds Ratio con un intervalo de confianza al 95% para

cada estudio.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 4 estudios. No se evidenció el riesgo de preeclampsia en adolescentes

embarazadas (OR = 0.93, IC 95% 0.69 – 1.25) ni hemorragia puerperal (OR = 0.86, IC 95% 0.74 – 0.99). Por

otro lado, se mostró el riesgo de eclampsia (OR = 2.43, IC 95% 1.29 – 4.58) en adolescentes embarazadas,

pero con alta heterogeneidad entre los estudios (I2 = 76%).

Conclusiones: Se evidenció un riesgo de eclampsia en adolescentes embarazadas, pero no en

preeclampsia ni hemorragia puerperal; sin embargo, estos resultados deben de tomarse con cautela.

Registro de protocolo: CRD42021286725 (PROSPERO)

Palabras claves: preeclampsia, eclampsia, hemorragia postparto, adolescente, mujeres embarazadas.

(Fuente: DeCS BIREME).

INTRODUCTION

Adolescent pregnancy affects countries around the world to varying degrees and is thus considered a

public health issue (1). In recent years, approximately 16 million

pregnancies were recorded annually among adolescents aged 15 to 19 years worldwide, with an additional 2

million pregnancies occurring in adolescents under 15 years of age each year (2). In 2020, the global adolescent birth rate was 41 births per 1000

adolescents aged 15 to 19 years, with Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean being the only regions

exceeding this rate, with 108 and 61 births respectively (3). Notably, the

number of pregnant adolescents under 15 years of age continues to increase in Latin America and the

Caribbean (1, 3).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), early procreation is considered a high-risk pregnancy

due to complications that affect both maternal and child health (4).

Complications during pregnancy and childbirth are the second leading cause of death among adolescents

aged 15 to 19 years, as reported by the same organization (5).

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) identified maternal complications that increase maternal

mortality, which could be controlled if screened by healthcare personnel. These complications include

preeclampsia, eclampsia, puerperal hemorrhage, and puerperal sepsis (6).

Similarly, in the study by Kawakita et al., the complications of adolescent pregnancy in the United

States were investigated, revealing an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage (aOR=1.46; 95%

CI=1.10–1.95) and preeclampsia (aOR=1.44; 95% CI=1.17–1.77) in adolescents (7). However, in the study by Neal et al., a systematic review aimed at

determining the leading causes of maternal death in young women under 20 years of age found that the

main causes of maternal death in adolescents were similar to those in older women: hypertensive

disorders, hemorrhage, abortion, and sepsis. They found heterogeneity among studies from different

regions, so in some settings, hypertensive disorder was the most important cause of mortality in

adolescents compared to older women. (8).

Most systematic reviews on this topic have been conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa or various countries,

making comparisons between studies from different regions heterogeneous. Therefore, the present

systematic review focused on countries in a single region: Latin America and the Caribbean.

Our objective is to assess the risk of maternal complications in adolescent pregnancies in Latin America

and the Caribbean from 2012 to 2021, specifically focusing on the previously mentioned complications.

METHODS

Study design and search strategy

A systematic review was conducted, and the project was registered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021286725). The

research question involved a population of pregnant adolescent women in Latin America and the Caribbean,

with the exposure being adolescent pregnancy (≤19 years), the comparison being pregnant adult women

(20-35 years), and the outcome being the risk of specific maternal complications (preeclampsia,

eclampsia, puerperal hemorrhage, puerperal sepsis).

The search strategy was carried out by an experienced medical research librarian. Searches were

conducted in the following databases: PubMed, SCOPUS, Web Of Science, EMBase, LILACS, and SciELO. The

search strategy was broad, without restrictions by study type or year, except in PubMed and SCOPUS where

it was limited to studies from the past 10 years. The detailed search strategy can be found in the

Supplementary Material. Additionally, the search was limited to studies written in English, Spanish, and

Portuguese.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they contained numerical data from Latin American or Caribbean countries

addressing the research question. Articles published from 2012 onwards were included, specifically

case-control and cohort studies with a group of pregnant adolescents (≤19 years) and a control group of

pregnant adults (20-35 years) or groups within these age ranges.

Case reports, literature reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, experimental, and qualitative

studies were not eligible for inclusion. Studies that did not present separate findings for Latin

America and/or the Caribbean, those without full-text availability, and those focused on patients with

specific diseases were excluded.

Selection process

The search strategy for all the aforementioned databases was downloaded into EndNote 20 software to

remove duplicate articles. Subsequently, the articles were exported to the online software Rayyan

(https://www.rayyan.ai/) where two researchers (MAOM and MAPCA) independently reviewed the titles and

abstracts. All included articles proceeded to the full-text evaluation phase by the same two authors

(MAOM and MAPCA). In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer (VERC) was consulted. Finally, the

references of the included articles were reviewed to identify any missing articles.

Data extraction, risk of bias assessment, and qualitative analysis

Information from the selected articles in the final phase was independently collected by two authors

(MAOM and MAPCA) into a data collection table created in Microsoft Excel for Mac version 16.6. The table

included the following domains: author, year of publication, country of execution, study design, data

collection period, total number of participants in the adolescent group and their age range, total

number of participants in the control group and their age range, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and

outcomes (preeclampsia, eclampsia, puerperal hemorrhage, and puerperal sepsis).

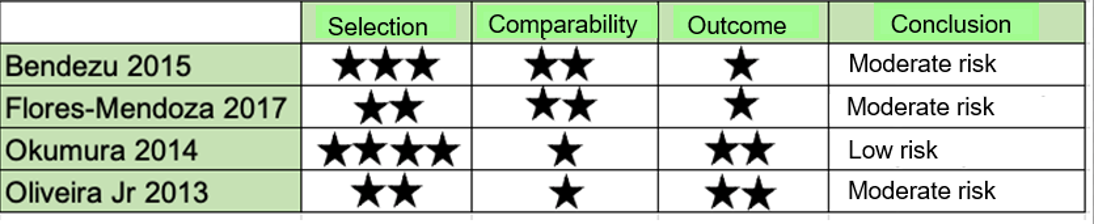

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the risk of bias for each included article, rating

the quality of the study as strong, moderate, or low. The NOS consists of 8 items divided into 3 risk of

bias domains: selection of study groups, comparability of groups, and verification of exposure and

outcome. Each item was awarded 1 point, except for the comparability item, which could receive 2 points

if warranted, with a maximum score of 9 points. The NOS considers a score of ≥7 as low risk of bias, 4-6

as moderate risk, and <4 as high risk of bias (9). This assessment was

independently conducted by two authors (MAOM and MAPCA) and compared and discussed to reach a consensus.

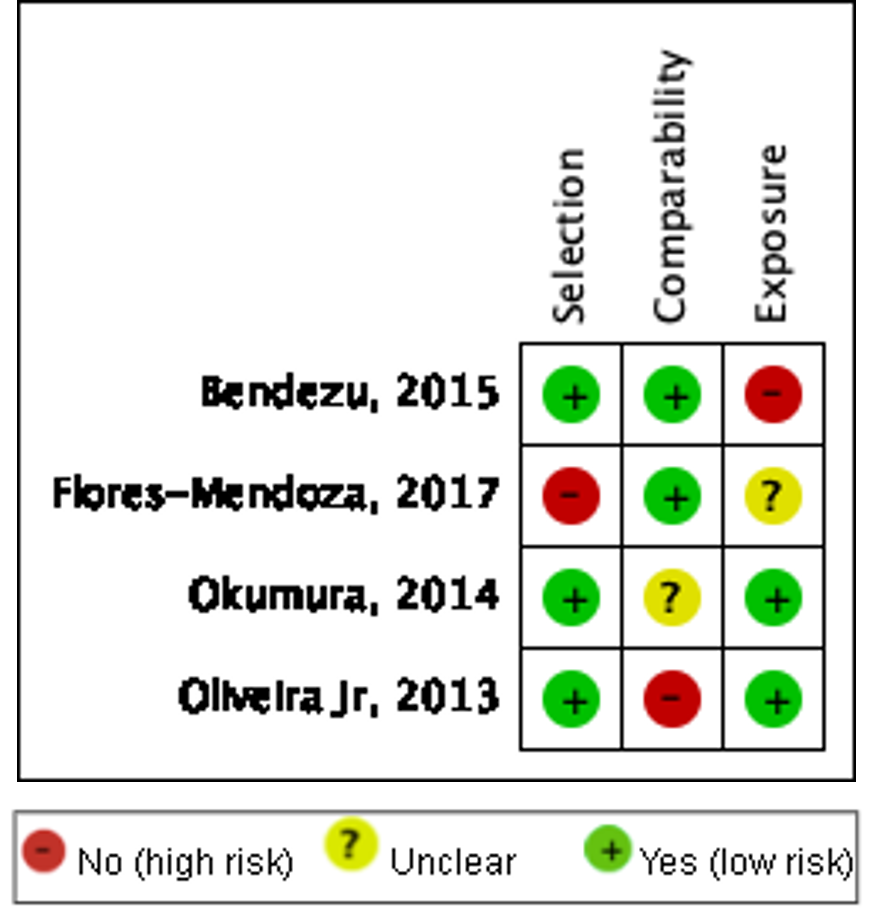

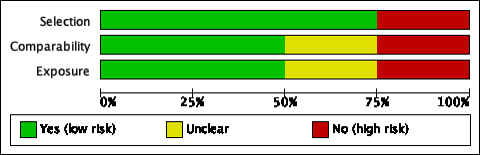

To illustrate the quality assessment of the studies, risk of bias graphs were created using Review

Manager version 5.4 software.

For the qualitative analysis, a narrative evaluation of all the included articles was conducted to

compare their methodological similarities and differences. The analysis included the following data:

author, year of publication, country of execution, study design, data collection period, total number of

participants in the adolescent group and their age range, total number of participants in the adult

group and their age range, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and outcomes. All these data were compiled

into a Microsoft Excel for Mac version 16.60 table.

Data collection flowchart

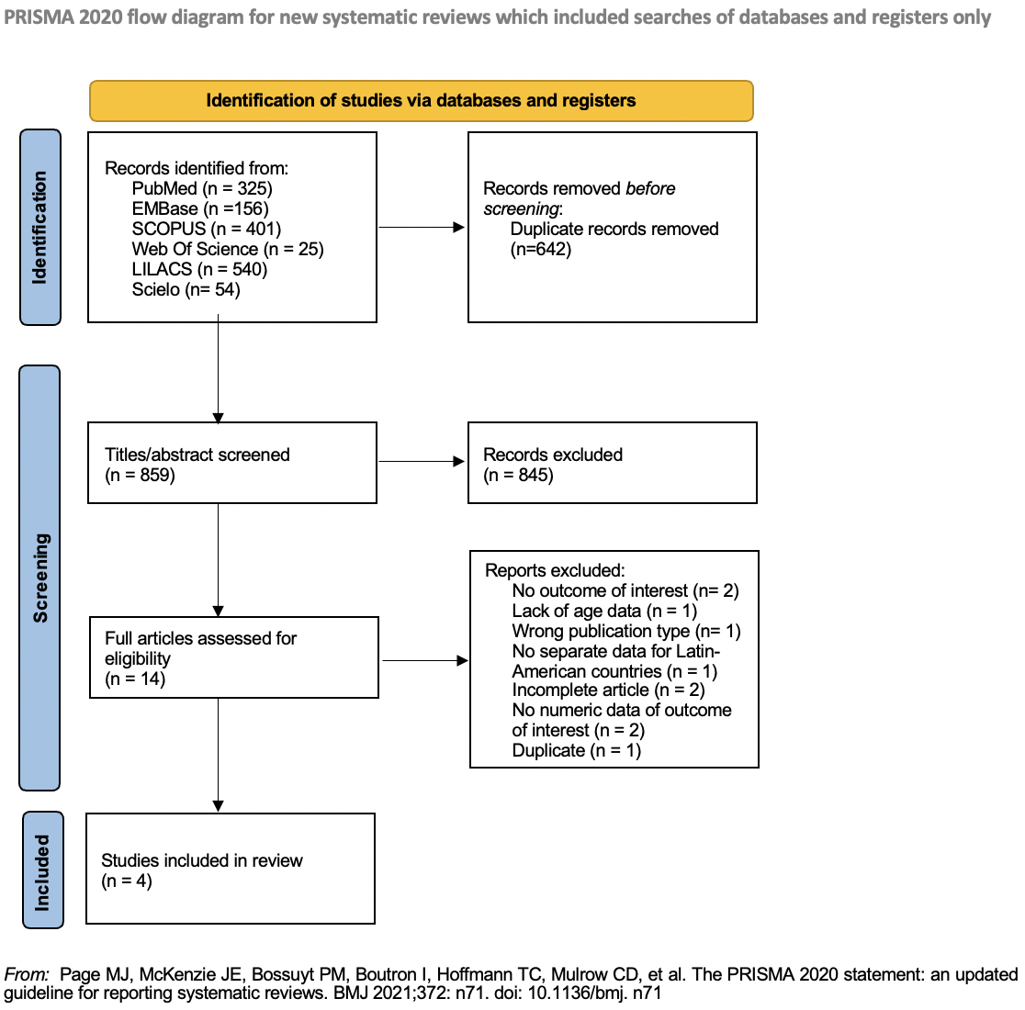

All evaluated and reviewed articles were outlined using a PRISMA flow diagram, illustrating the

selection process and the total number of included studies, as well as those that were excluded (10).

Summary measure and synthesis method

The summary measure used was the Odds Ratio (OR). The OR with a 95% confidence interval was extracted

from each study. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated using the I² statistic. A meta-analysis was

conducted comparing the raw ORs using a random-effects model with inverse variance. The meta-analysis

results were presented using Forest plot. The meta-analysis was developed using Review Manager 5.4

software.

Publication bias

The study included fewer than 10 articles, so a funnel plot was not performed to assess publication

bias.

Ethical considerations

This study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Human Medicine

at Universidad Ricardo Palma – Lima, Peru on 10/21/2021 (code PG-50-021). Additionally, it has been

drafted in accordance with the "PRISMA 2020 Statement for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses" (11).

RESULTS

Selection of results

The search strategy identified 1,501 potential studies, of which only 4 were included. No articles

meeting the inclusion criteria were found upon reviewing the references. After reviewing the titles and

abstracts, 845 studies were excluded, and 10 studies were excluded after reading the full articles. One

article met the inclusion criteria but was a duplicate with the title in English (12). Additionally, another article could have been included, but it was

incomplete, missing tables with information on the variables of interest (13). The exclusions at each

phase with their explanations are described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of the literature review

Characteristics of the studies

Of the total included studies, two (50%) were conducted in Peru (14, 15), one (25%) in Mexico (16), and one (25%)

in Brazil (17). Additionally, two (50%) of these studies used medical

records of the participants as their source of information (14, 15), one (25%) utilized data from a demographic survey followed by personal

interviews (17). One study (25%) did not specify how the information was

obtained; however, it was the only one to specify the exclusion criteria it used (16). The characteristics of the included studies are detailed in Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias for the 4 included articles was evaluated using the NOS for case-control studies. The

data were recorded in Review Manager 5.4 software, which was modified according to the NOS with 3

sections: selection, comparability, and outcome (Table 2).

The category with the highest rating was selection (Figures 2a and 2b). None of the studies used the

checklist to describe their studies.

|

Author |

Year of publication |

Country of execution |

Study design |

Data collection period |

Adolescent group participants |

Adolescent age range |

Adult group participants |

Adult age range |

Selection criterio |

Results |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bendezú et al |

2015 |

Peru |

Case-control, retrospective, patient medical records |

July 1, 2013 - June 30, 2014 |

177 |

≤ 19 years |

177 |

20-34 years |

Adolescents in labor or women with previous adolescent childbirth. |

Postpartum hemorrhage Sepsis |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Flores-Mendoza et al |

2017 |

Mexico |

Analytical, retrospective |

2013-2014 |

256 |

≤ 19 years |

779 |

>19 years |

Adolescents ≤ 19 years; excluded incomplete data and those transferred to other hospitals.. |

Preeclampsia with and without severe signs. Eclampsia |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Okumura et al |

2014 |

Peru |

Analytical, retrospective, patient medical records |

January 1, 2000 - December 31, 2010 |

15,685 |

10-19 years |

52,008 |

>20-35 years |

Pregnant women aged 10 to 35 who gave birth with gestational age >20 weeks, birth weight >500g, and complete data. |

Preeclampsia Eclampsia Puerperal hemorrhage |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oliveira Jr. et al |

2013 |

Brazil |

Retrospective, Brazilian health demographic survey |

2006-2007 |

420 |

15-19 years |

3,705 |

>20-34 years |

Women with at least one pregnancy within the age range. |

Eclampsia Puerperal hemorrhage |

Table 2. Risk of bias assessment using the NOS

A

B

Figure 2. Risk of Bias. A: Risk of bias for each included study. B: Summary of risk of bias for the included studies.

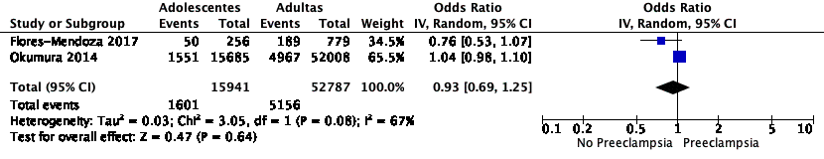

Preeclampsia

Two of the included studies have results on preeclampsia. Flores-Mendoza et al. divided preeclampsia

into two groups: with severe signs and without severe signs (16); for data

processing in the present study, the variable used was preeclampsia without severe signs. On the other

hand, Okumura et al. based their diagnosis of preeclampsia on the ICD-10 (International Classification

of Diseases) code records available for each patient (15).

The ORs of both studies contain the unit: 0.76 (95% CI 0.53 – 1.07) and 1.04 (95% CI 0.98 – 1.10)

respectively, indicating no difference between the study group and the control group regarding

preeclampsia. Despite not all studies having the same definition of preeclampsia, a meta-analysis was

conducted. The summary OR calculation yielded 0.93 (95% CI 0.69 – 1.25) with high heterogeneity (I² =

67%) (Figure 3A).

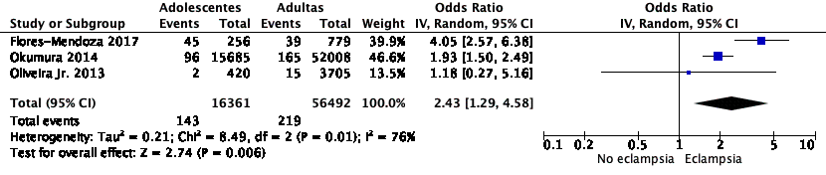

Eclampsia

Three of the included studies reported results on eclampsia. Oliveira Jr. et al. defined eclampsia as

“seizures during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum,” whereas Okumura et al. relied on ICD-10 code

records available for each patient to diagnose eclampsia (15). The third

study did not specify the definition used for eclampsia. Flores-Mendoza et al. reported a high risk of

eclampsia in adolescents compared to adults (OR 4.05, 95% CI 2.57 – 6.38) (16), similar to Okumura et al. (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.50 – 2.49) (15). However, Oliveira Jr. et al. found no difference between the groups

(17). Despite the varying definitions of eclampsia, a meta-analysis was

conducted. The summary OR calculation yielded 2.43 (95% CI 1.29 – 4.58), which was statistically

significant, but with high heterogeneity (I² = 76%) (Figure 3B).

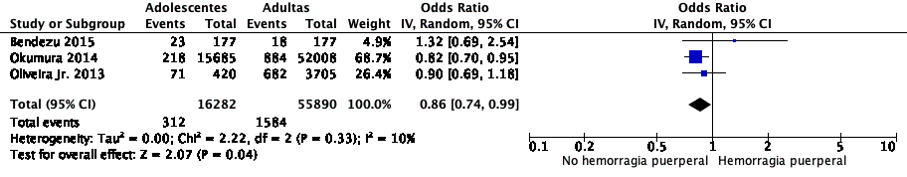

Puerperal hemorrhage

Three of the included studies have results on puerperal hemorrhage. Oliveira Jr. et al. defined

puerperal hemorrhage as “heavy bleeding that soaks clothes in the first 3 days postpartum” (17). Okumura et al., on the other hand, based their diagnosis of puerperal

hemorrhage on ICD-10 code records available for each patient (15). Bendezu

et al. did not define the variable and analyzed it according to the clinical records (14). The latter study reported no significant difference between the study

and control groups regarding puerperal hemorrhage (OR 1.32, 95% CI 0.69 – 2.54), similar to Oliveira Jr.

et al. (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.69 – 1.18). However, Okumura et al. showed statistical significance (OR 0.82,

95% CI 0.70 – 0.95) (15). Despite the varying definitions of puerperal

hemorrhage, a meta-analysis was conducted. The summary OR calculation yielded 0.86 (95% CI 0.74 – 0.99),

which was not statistically significant and presented low heterogeneity (I² = 10%) (Figure 3.C).

a

b

c

A: Forest plot of the risk of preeclampsia in pregnant adolescents in Latin America. B: Forest plot of the risk of eclampsia in pregnant adolescents in Latin America. C: Forest plot of the risk of puerperal hemorrhage in pregnant adolescents in Latin America.

Figure 3. Forest plot.

Puerperal sepsis

Only one study included puerperal sepsis in its analysis. Bendezu et al. reported one case of puerperal

sepsis in pregnant adolescents compared to no cases in pregnant adults, with an OR of 3.02 (95% CI 0.12

– 74.56), which was not statistically significant.

Synthesis of Results

All studies included pregnant adolescents aged ≤19 years and a control group of pregnant adults aged 20

years or older. Not all studies included all variables of interest or their definitions. Three of the

included studies had a moderate risk of bias, and one had a low risk. The included studies originated

from Latin American countries due to the limited scientific evidence from the Caribbean.

No risk of preeclampsia was found in pregnant adolescents (OR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.69 – 1.25) nor for

puerperal hemorrhage (OR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.74 – 0.99). However, an increased risk of eclampsia (OR =

2.43, 95% CI 1.29 – 4.58) was found in pregnant adolescents, with high heterogeneity among studies (I² =

76%).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this systematic review was to assess the risk of maternal complications in adolescent

pregnancies in Latin America and the Caribbean from 2012 to 2021. The maternal complications included

were preeclampsia, eclampsia, puerperal hemorrhage, and puerperal sepsis, as identified by PAHO as

increasing maternal mortality in Latin America and the Caribbean (6). However, due to the limited

scientific production in the Caribbean, studies from this region could not be included.

The results of this systematic review did not show a risk of puerperal hemorrhage in pregnant

adolescents (OR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.74 – 0.99) in Latin America. These results are similar to those found

by Kawakita et al. in their cohort study conducted in the United States, where pregnant adolescents aged

16-19 years did not show a risk of puerperal hemorrhage (OR = 1.10, 95% CI 0.98 – 1.24) compared to

those ≤15 years, who did show a risk (OR = 1.46, 95% CI 1.10 – 1.95) (7).

Similarly, Althabe et al., in a prospective study in middle-low income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa

and Latin America, did not find a risk of puerperal hemorrhage in the <15-year-old pregnant

adolescent group (OR = 0.62, 95% CI 0.29 – 1.32) or the 15-19-year-old group (OR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.85 –

1.03) (18). However, these findings differ from Conde-Agudelo et al., who

found a risk of puerperal hemorrhage in pregnant adolescents (aOR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.19 – 1.27) in the

Latin American Center for Perinatology and Human Development database (19).

In the systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Gronvik and Fossgard in Sub-Saharan Africa, a

risk of preeclampsia/eclampsia (OR = 3.52, 95% CI 2.26 – 5.48) was found in adolescents <18 years

without showing heterogeneity (I² = 0%) (20). In contrast to our results,

in this systematic review, we did not find a risk of preeclampsia (OR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.69 – 1.25) with

high heterogeneity among the included articles (I² = 67%), but we did find a risk of eclampsia (OR =

2.43, 95% CI 1.29 – 4.58), though with high heterogeneity (I² = 76%). Conversely, in Althabe et al.'s

prospective study, no risk of hypertensive diseases was found in the <15-year-old pregnant adolescent

group (OR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.21 – 1.55) or the 15-19-year-old group (OR = 1.11, 95% CI 0.98 – 1.25)

(18).

Despite the high heterogeneity found among the selected studies, it was considered appropriate to

conduct a meta-analysis due to the limited information available on this topic over the past 10 years in

the literature.

The public health relevance of the findings from this systematic review and meta-analysis is significant

given the high rates of adolescent pregnancy in Latin America and the Caribbean, a region already facing

numerous challenges in maternal and child health. The results indicate that pregnant adolescents have an

increased risk of developing eclampsia compared to adult women, a severe complication that can lead to

maternal and perinatal death if not properly managed (21). Identifying this

specific risk highlights the urgent need to implement public health policies and programs focused on

preventing adolescent pregnancy and improving access to quality prenatal care for pregnant adolescents

(22).

Moreover, the absence of a significant risk of preeclampsia and puerperal hemorrhage in pregnant

adolescents (23, 24), despite the high heterogeneity

found, underscores the importance of continued research and robust data collection in this area. The

findings suggest that public health interventions should be tailored and evidence-based, considering the

variability in results across different studies and contexts. It is crucial for health systems in Latin

America and the Caribbean to strengthen their capacities to effectively identify and manage obstetric

complications in adolescents and promote sexual and reproductive education to reduce the incidence of

unintended adolescent pregnancies (25).

Limitations The majority of the studies found were case-control studies, published between 2012 and

2021, in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. Some included studies did not provide definitions for the

variables of interest. There were limited studies from the Caribbean. Meta-analyses have their own

limitations and biases, which is why the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to assess the risk of bias in

case-control studies.

High-quality scientific production related to the risk of developing maternal complications in pregnant

adolescents over the past 10 years in Latin American and Caribbean countries is scarce, considering

significant differences between various regions worldwide. It would be ideal to increase high-quality

scientific production on this topic, given that it is a public health issue in our region. Future

research addressing adolescent pregnancy in Latin America and the Caribbean should use multiple age

subgroups for adolescents and adjust for all important confounding factors.

CONCLUSIONS

The study findings indicate a risk of eclampsia in pregnant adolescents aged 19 years or less in Latin

America; however, these results should be interpreted with caution.

No risk of preeclampsia or puerperal hemorrhage was found in pregnant adolescents aged 19 years or less

in Latin America.

Authorship contributions:

MAM and MACA participated in the conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis,

investigation, methodology, visualization, drafting of the original manuscript, and

reviewing and editing the article. VERC participated in supervision, validation, and

reviewing and editing the article. All authors approved the final version of the article for

publication.

Financing:

This study was self-funded.

Declaration of conflict of interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Recevied:

February 5, 2024

Approved:

April 29, 2024

Correspondence author:

Maria A. Oviedo-Mendoza.

Address:

Jr. Parque Prescott 118 - Salamanca, Lima – Perú.

Phone:

(01) 7080000

E-mail:

maria.oviedo@urp.edu.pe

Article published by the Journal of the faculty of Human Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University. It is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creatvie Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), that allows non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. For commercial use, please contact revista.medicina@urp.edu.pe.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES