CLINIC CASE

REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA HUMANA 2024 - Universidad Ricardo Palma10.25176/RFMH.v24i3.6549

ACUTE BENIGN CHILDHOOD MYOSITIS DUE TO Bartonella henselae: A RARE PATHOGEN

MIOSITIS AGUDA BENIGNA INFANTIL POR Bartonella henselae: UN PATÓGENO INFRECUENTE

José Paz-Vargas

1,2,a

1,2,a

Gabriela Rivera-Saucedo

2,b

2,b

Cynthia Legna Huby Muñoz

1,3,c

1,3,c

Marco Antonio Alpiste Díaz

1,c

1,c

1 National Institute of Child Health - Breña. Lima, Peru

2 Faculty of Human Medicine. Ricardo Palma University. Lima, Peru

3 Faculty of Human Medicine. San Martín de Porres University. Lima, Peru

a Pediatric Resident Physician

b Surgeon

c Pediatrician

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Acute benign myositis of childhood (ABIM) is an inflammatory pathology of the

musculoskeletal system, usually manifesting with pain in the lower limbs associated with elevation of

creatine phosphokinase (CPK). It is a rare condition, but if it occurs, it appears after a flu case,

frequently associated with influenza A and B viruses. Objective: To present the case of a

school-age girl with myalgia in lower limbs, fever, and elevated CPK, diagnosed with ABIM, with positive

IgG to Bartonella henselae.

Materials and methods: This is a case report. The patient presented with symptoms suggestive of

ABIM, including myalgia, fever, and elevated CPK. Diagnosis was confirmed with positive IgG to

Bartonella henselae.

Results: The case highlights the rarity of ABIM and its potential association with Bartonella

henselae infection, which has not been previously reported in Peru.

Conclusions: Reporting this case underscores the need for awareness of ABIM and its possible

etiological agents, such as Bartonella henselae, to guide appropriate management and reduce unnecessary

hospitalizations.

Keywords: Myositis; Bartonella henselae; Cat scratch disease (CSD).

RESUMEN

Introducción: La miositis aguda benigna de la infancia (MABI) es una patología inflamatoria del

sistema músculo esquelético, suele manifestarse con dolor en miembros inferiores asociado a elevación de

creatina fosfoquinasa (CPK). Es una afección poco frecuente, pero de presentarse, aparece posterior a un

cuadro gripal, asociado frecuentemente al virus influenza A y B.

Objetivo: Presentar el caso de una niña en edad escolar con mialgia en miembros inferiores,

fiebre y elevación de CPK, diagnosticada con MABI, con IgG positiva para Bartonella henselae.

Materiales y métodos: Se trata de un reporte de caso. La paciente presentó síntomas sugestivos

de MABI, incluyendo mialgia, fiebre y elevación de CPK. El diagnóstico se confirmó con IgG positiva para

Bartonella henselae.

Resultados: El caso resalta la rareza de la MABI y su posible asociación con la infección por

Bartonella henselae, lo cual no ha sido reportado previamente en Perú.

Conclusiones: El reporte de este caso subraya la importancia de la conciencia sobre la MABI y

sus posibles agentes etiológicos, como Bartonella henselae, para guiar un manejo adecuado y reducir

hospitalizaciones innecesarias.

Palabras clave: Miositis; Bartonella henselae; Enfermedad por rasguño de gato (CSD).

INTRODUCTION

Platelets are blood components that play an important role in cell regeneration through the release of

growth factors (GF), cytokines, and inflammatory response (1,2). The main GFs released by the alpha granules of platelets are

platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which are responsible

for cellular chemotaxis, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix production (3,4). Epidermal growth factor (EGF, fibroblast proliferation) and vascular

endothelial growth factor (VEGF, angiogenesis) are other factors released by platelets that together

play an important role in hemostasis, proliferation, and remodeling during the different phases of wound

healing (5).

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy

PRP therapy has gained popularity in regenerative medicine due to its potential to provide a high

concentration of GFs (6). PRP is an autologous blood component that contains

a high number of platelets and is typically obtained from peripheral blood (7). It is used in various clinical fields such as traumatology,

ophthalmology, dentistry, cosmetic surgery, and wound healing, serving as a therapy to enhance tissue

regeneration (8). However, its use has some drawbacks, such as the method of

obtaining it, which can cause pain or injury to nerves or blood vessels at the puncture site (9,10). Additionally, in patients with compromised immune

systems, there may be an abnormal expression of growth factors, potentially impairing their regenerative

function (11).

PRP from umbilical cord (UC) blood

PRP can also be easily obtained from umbilical cord (UC) blood. The comparison between peripheral blood

and UC blood will differ in both the type and quantity of growth factors they contain (12). Studies mention that PRP obtained from UC blood has therapeutic

advantages over that obtained from peripheral blood as it contains a higher concentration of GFs. Buzzi

et al. 13 compared the GF content of UC and peripheral blood, finding higher levels of EGF, TGF-β, PDGF,

and VEGF in UC samples. This is similarly demonstrated by Murphy et al. 3 and Parazzi et al. 14. The

former showed higher values of PDGF-BB and VEGF (p<0.01) in PRP from UC blood, while the latter

reported elevated concentrations of angiogenic factors (VEGF, growth hormone, erythropoietin, and

resistin) in platelet gel prepared from UC blood compared to peripheral blood.

Kinetics of growth factors in PRP

The concentration of GFs released from PRP varies over time, with kinetics studies determining the speed

at which they reach their maximum concentration (15). Roh et al. 2, using

PRP from peripheral blood, observed that the levels of factors such as PDGF-BB and VEGF remained

constant for 7 days, suggesting that these findings would be useful in guiding PRP treatment in

regenerative medicine. Despite the widespread use of PRP with GFs to enhance wound healing and tissue

regeneration, little is known about its kinetics when obtained from UC blood. This study could provide

insights into its behavior and potential therapeutic utility. Therefore, the objective of this study is

to evaluate the release of PDGF-BB from PRP obtained from UC blood at different time points.

METHODS

Study design and area

An in vitro experimental study was conducted to evaluate the kinetics of PDGF-BB release in PRP obtained

from UC blood from term deliveries attended at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Service of the Hospital

Nacional Cayetano Heredia during May 2023.

Population and sample

UC blood samples were collected from 6 term deliveries of healthy pregnant women aged between 18 and 36

years who had previously agreed to participate and signed an informed consent form. Pregnant women with

a history of blood disorders, metabolic disorders (diabetes mellitus, obesity, etc.), hemoglobin < 11

g/dL, platelets < 150 x 10^3 µL, autoimmune diseases, concomitant medication such as antiplatelet

agents, corticosteroids, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the last 15 days, or inflammatory or

infectious processes according to medical history were excluded from the study.

Procedures

Obtaining umbilical cord blood

In utero collection was performed, where, once the newborn was delivered and assessed, the cord was

clamped and cut, and blood was collected. A total of 7 cc of UC blood was collected into tubes

containing 3.2% sodium citrate anticoagulant after puncturing the umbilical vein with a syringe. This

procedure took less than 5 minutes. The samples were then taken to the Hemotherapy and Blood Bank

Service for processing, where basal platelet counts were performed before centrifugation using the

CELL-DYN Emerald hematology analyzer from Abbott.

Preparation and activation of PRP

The collected samples were centrifuged at 900 g for 10 minutes. After centrifugation, the lower third of

the obtained plasma, corresponding to PRP, was separated and transferred to a sterile glass tube to

perform post-centrifugation platelet counts. The PRP was then activated with 10% calcium gluconate

(Glu.Ca) at 10%. The PRP was divided into 4 aliquots and labeled as follows: (i) without activator, (ii)

1 hour, (iii) 24 hours, and (iv) 48 hours. In a proportion of 1/10, 50 µL of Glu.Ca and 450 µL of PRP

were added to aliquots (ii), (iii), and (iv). Each group, except for (i), was incubated at 37°C and 5%

CO2 for 1 hour, 24 hours, and 48 hours, respectively. After the incubation period, they were stored in a

-40°C freezer for subsequent measurement of PDGF-BB (Figure 1).

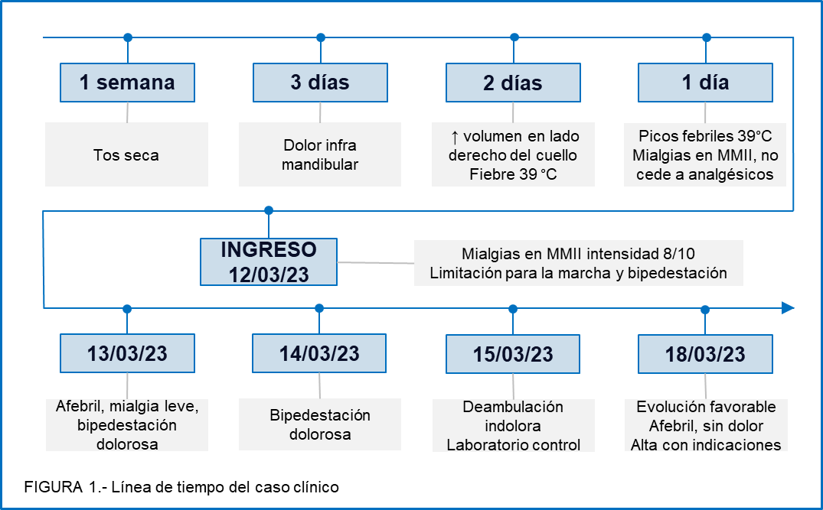

Myositis is a benign inflammatory condition characterized by muscle fiber necrosis due to degenerative changes from a previous infection. Being limited to muscle fiber damage, it is transient, resolves without sequelae, and has a good prognosis. Regarding gender, it is found that males are more affected, but in our case, it affected a female patient. Reports show that most cases are found in preschool and school-aged children, which is consistent with our patient's age.

The most frequent etiology is viral, highlighting influenza A and B viruses. Additionally, it can be caused by enteroviruses, hepatitis B or C viruses, and even the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), with Mycoplasma, Brucella, and Bartonella being less common(8). In this case, Bartonella henselae, considered an atypical bacterium(9), is the cause of acute myositis, as previously reported(8).

Our patient presented with the classic symptoms of myositis, characterized by preceding fever, cough, rhinorrhea, and coryza. Subsequently, she developed calf pain and some degree of claudication. However, it is worth mentioning that other parts of the body, such as the thighs, neck, back, and arms, can also be affected, which fortunately was not the case for our patient.

Although the initial suspicion of this pathology is clinical, certain tests are essential to reach a diagnosis. A significant increase in the enzyme CPK is evident in these patients, sometimes reaching 20-30 times its normal value and returning to normal within weeks. Despite high CPK levels, patients rarely associate with myoglobinuria or rhabdomyolysis(8), but it is necessary to monitor renal function if suspected. For etiological diagnosis, viral IFI, which evaluates 7 viruses at the institution, was requested. The results were negative, showing no reactivity for any of the evaluated viruses. On the other hand, Bartonella henselae IgG was requested, resulting in a dilution of 1:1000. The CDC recommends Bartonella henselae IgG as the gold standard, with a specificity of 92-98% and a sensitivity of 88-100%(10). The CDC cutoff is 1:64, while in Peru, 1:256 confirms the case. In our case, the patient had a result of 1:1000, indicating active B. henselae(11).

Parents and healthcare personnel show much concern for BACM patients due to their symptoms, necessitating the exclusion of other conditions that can be confused with BACM, such as infectious, neurological, and muscular pathologies. These include dermatomyositis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, polymyositis, muscular dystrophy, rhabdomyolysis, transverse myelitis, dengue, and others(3). Therefore, a clear medical history and a comprehensive physical examination are essential to guide the diagnosis appropriately.

Hospitalization criteria include children under 2 years, a family history of neuromuscular disorders, a second episode of BACM, pathological neurological examination, poor general condition, dark urine, or altered renal function levels. However, our patient did not present any of these criteria and should have been treated on an outpatient basis(12).

The management of BACM is symptomatic with analgesics(5, and the treatment for cat scratch disease includes macrolides or tetracyclines(8,13. Our patient received analgesic treatment with metamizole and ketorolac, and also with azithromycin, a macrolide, at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day, completing 5 days of treatment. The patient showed good progress, with good ambulation by the fifth day of hospitalization, as reported in other studies(6).

CONCLUSION

BACM is a benign, transient condition with a good prognosis, whose diagnostic suspicion is clinical, requiring a thorough history and physical examination. While viruses are the most frequent etiology, notably influenza A and B, bacteria, fungi, and parasites can also cause BACM. Therefore, it is essential to confirm the etiological agent early to tailor the therapy. Treatment is symptomatic and usually resolves without complications; however, it is important to distinguish if the patient meets hospitalization criteria to avoid unnecessary admissions.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

Authorship Contributions: The authors contributed to the conception of the article,

literature

search, writing, and approval of the final version.

Funding: Self-funded.

Received: June 12, 2023

Approved: June 24, 2024

Correspondence: José Christopher Paz Vargas

Address: Av. Benavides 5440, Surco, Lima, Peru

Phone: +51 982489222

Email: josepazvargas23@gmail.com

Article published by the Journal of the faculty of Human Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University. It is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creatvie Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), that allows non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. For commercial use, please contact revista.medicina@urp.edu.pe.

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS