Introduction

The solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon tumor, with an incidence rate of 2.8 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. This tumor primarily affects the pleura, is generally benign and often found incidentally; however, large tumors tend to cause symptoms

1, 2

. Rarely, this tumor presents with paraneoplastic syndromes, such as persistent hypoglycemia; this association is called Doege–Potter syndrome

2, 3

. The definitive treatment for this condition is surgical resection of the tumor, ideally after diagnosis and classification through biopsy

4

.

Here, we present a case of a patient with Doege–Potter syndrome who was diagnosed and treated at the Hospital Nacional Hipólito Unanue in Lima, Peru.

Case Report

A 70-year-old female patient from Huancavelica, Peru, with no relevant personal or family medical history, was admitted to the Pulmonology Department of the Hospital Nacional Hipólito Unanue. She had been suffering from the illness for four years, with productive cough with mucoid sputum, oppressive pain in the left hemithorax, and progressively worsening dyspnea. Family members noted that for the past 10 months, the patient had been experiencing increasingly frequent episodes of disorientation, psychomotor agitation, or drowsiness.

Upon admission, physical examination revealed reduced thoracic expansion in the left hemithorax, dullness, and decreased vesicular breath sounds in the lower third of the left hemithorax. No neurological abnormalities were found.

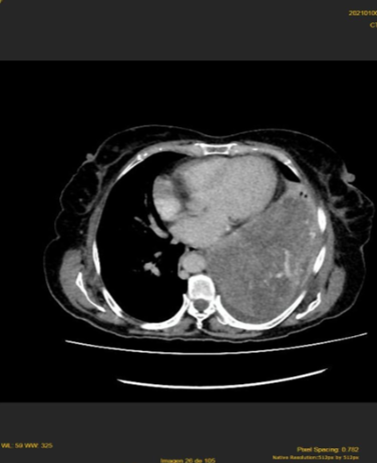

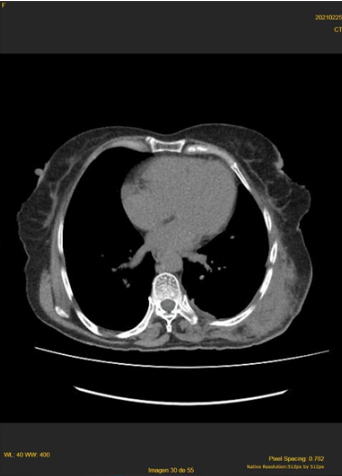

A chest X-ray showed a homogeneous radiopacity in the lower half of the left lung field, and a spiral thoraco-abdominal multidetector computed tomography scan revealed an extensive solid tumor occupying the lower two-thirds of the left hemithorax, displacing the diaphragm and intra-abdominal structures caudally, measuring 200 x 156 x 165 mm, with significant contrast enhancement. There was no infiltration of bone structures, the chest wall, or visceral organs, nor were there mediastinal lymphadenopathies. Left pleural effusion was observed (Figure 1). In the abdomen, no abnormalities were found, except for the caudal displacement of the diaphragm, spleen, and left kidney.

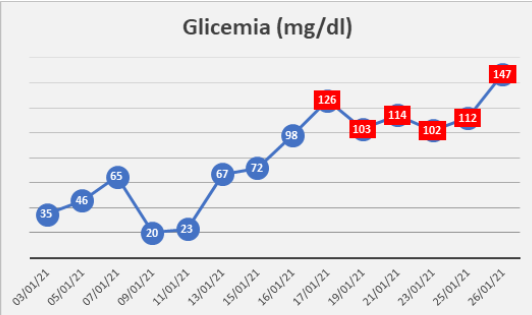

Laboratory tests reported C-peptide levels of 0.8 ng/ml (1.1 – 4.4), basal insulin of 0.2 U/ml (2.6 – 24.9), CA125 at 97.87 U/mL (<33.0 U/ml), CA 15-3 at 8.06 U/ml (0 – 28.5), CA 19.9 at 12.56 U/ml (0 – 34), and CEA at 4.11 ng/ml (<5.00). Additionally, the patient experienced recurrent hypoglycemia (Table 1), which required continuous intravenous dextrose infusion. Other tests were within normal limits.

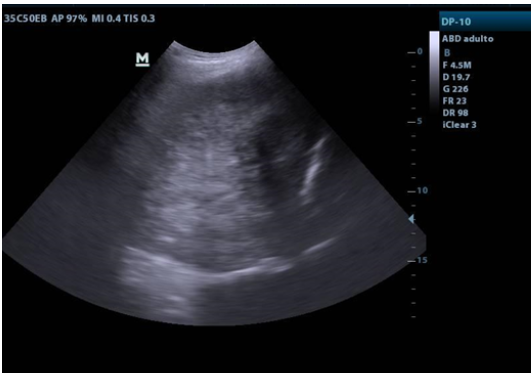

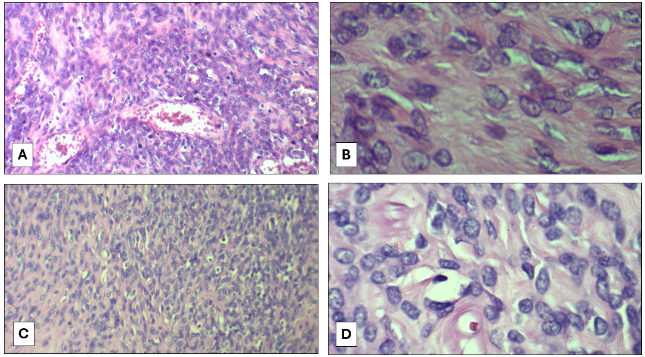

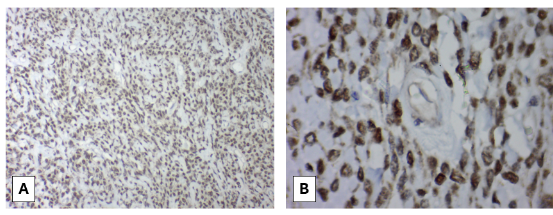

An ultrasound-guided transthoracic biopsy was performed using an 18G x 16cm core needle with trocar (Figure 2). The histopathological study reported a solitary fibrous tumor (Figure 3), and immunohistochemistry was positive for STAT6 (Figure 4).

With these results, the patient underwent thoracotomy with resection of the giant tumor and partial resection of the left hemidiaphragm (Figure 5). In the pathological anatomy study, a 4230 g pleural tumor measuring 27 x 20 x 14 cm, with a smooth, light brown, shiny, lobulated surface was observed macroscopically. Microscopically, the biopsy diagnosis of a solitary fibrous tumor was confirmed, with areas of hypercellularity and hypocellularity, focal necrosis in 10%, and mitoses up to 2/10 HPF. Immunohistochemistry was positive for STAT6.

Serum glucose levels normalized after the removal of the thoracic tumor (Table 1), and 23 days after hospitalization, with favorable evolution, the patient was discharged. In follow-up outpatient visits, the patient remained asymptomatic, with a CT scan 30 days later showing no evidence of recurrence (Figure 6).

After data collection, the patient returned to Huancavelica. She was verbally informed about the case report, and she verbally agreed to its publication, with confidentiality of her personal data maintained.

Discussion

The solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon fibroblastic mesenchymal tumor, first described at the pleural level, which is the most frequent site of involvement, and has been documented in almost all anatomical sites and organs

1, 2

. About 10% of cases are extrathoracic, with the most common site being the abdomen

1, 2

. The incidence rate is only 2.8 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, and the majority of cases occur in the sixth and seventh decades of life, affecting both sexes equally

1, 2

. A smaller number of cases are malignant, with approximately 90% being benign

3, 4

.

Between 50% and 80% of cases are asymptomatic, making the tumor an incidental finding in radiological imaging

2

. SFTs typically present as painless, slow-growing masses, and in some cases, may cause symptoms due to the mass effect or pressure on adjacent structures

1

Symptoms can vary and may include dyspnea, chest pain, cough, or hemoptysis

1, 2, 5

.

In rare instances, SFT may present with paraneoplastic syndromes, the most commonly described being tumor-induced hypoglycemia in non-islet cell tumor hypoglycemia (NICTH), known as Doege–Potter syndrome

1

. his syndrome is characterized by persistent refractory hypoglycemia, suppressed serum insulin, low serum growth hormone and C-peptide, increased tumor production of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and normal or elevated IGF-2 levels

2, 6

. IGF-2 may induce hypoglycemia by binding to insulin receptors in target tissues, transporting glucose to muscles, and inhibiting gluconeogenesis in the liver and lipolysis in adipocytes

2

Most tumors associated with hypoglycemia are large, suggesting that hypoglycemia is directly related to tumor size

5

. Hypoglycemia is more frequently observed in women than men and when the tumor is located in the right hemithorax

7

After tumor resection, symptoms gradually disappear, making surgery the definitive treatment

2

.

The size of the tumor varies, and it is more commonly found in the right pleural cavity, often exceeding 20 cm in diameter

3, 8

These tumors are well-circumscribed, with a smooth surface, and often have a lobulated appearance

1, 9, 7

.

Imaging studies play an important role in diagnosis; chest X-rays may reveal well-defined masses of varying sizes, sometimes associated with pleural effusion

5

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography typically shows a low-density tumor with abundant vascularization, well-circumscribed, and with areas of necrosis if large

1

.

Histologically, SFTs are highly variable, composed of cells with ovoid to spindle-shaped nuclei, within a collagenous stroma with areas of dense hyalinization

1, 10

Mitotic activity in these tumors is generally low, typically less than 5 mitoses per 2 mm2; higher mitotic rates and hypercellularity are signs of tumor aggressiveness

7, 13

Immunohistochemistry and molecular diagnostic studies are crucial for diagnosis; markers such as CD34, vimentin, CD99, and BCL2 are variably expressed in SFTs

1, 8, 14

It is important to note that these markers may also be positive in other mesenchymal neoplasms, so the identification of the fusion genetic marker between NAB2 and STAT6 with a nuclear pattern, which is highly specific and sensitive, has helped differentiate SFTs from other tumors

1, 11

The STAT6–NAB2 product results from an inversion at the 12q13 locus that induces the expression of early growth response, demonstrated by polymerase chain reaction in 90% of SFT cases

1

.

Pre-treatment biopsy for tumor diagnosis and classification is ideal to ensure an accurate diagnosis

12

Fine needle aspiration biopsy, transthoracic core needle biopsy, and open incisional biopsy have been used; however, transthoracic and fine needle aspiration biopsies have low diagnostic yields, with some series reporting a 43% success rate

1

Diagnostic yield decreases in lesions over 5 cm, as there is a higher likelihood of necrosis and unsatisfactory samples

12

Ultrasound-guided biopsy of a pleural-based thoracic lesion has diagnostic accuracy similar to CT-guided biopsy, with lower complication rates and shorter procedure times

13

.

A multidisciplinary approach is necessary for treatment

2

Initial treatment should include glucocorticoids, either orally or intravenously, to prevent hypoglycemia

10

The cornerstone of treatment is complete surgical resection

2, 3, 4

If further surgeries are required due to recurrence, these become increasingly challenging, as there may be more adhesions

14

To prevent this, adjunctive therapies such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, cryoablation, or embolization may be considered, although these are not used in all cases

7, 10

The surgical approach depends on the tumor's location and the structures involved

3

Surgery is associated with low local recurrence and progression rates

1

In highly vascularized tumors, embolization therapy followed by surgical resection may be considered to reduce the risk of bleeding

2

Radiotherapy or chemotherapy is not recommended for routine use due to limited data given the relatively low incidence of SFT

2, 8, 12

These therapies have been associated with poor responses

11

Malignancy has been linked to having three or more of these six factors: parietal pleural location, size ≥10 cm, hypercellularity, nuclear atypia, ≥4 mitoses/10 high-power fields, and/or necrosis

15

Hypoglycemia is associated with malignancy, making it a poor prognostic indicator; however, after surgical treatment, satisfactory outcomes are achieved, with a five-year recurrence-free rate of approximately 80%

7

Nonetheless, the recurrence rate of malignancy has been reported in 63% of cases, making long-term follow-up essential for early detection of recurrent or metastatic disease

14

he recommended follow-up period is every three to six months for two years, then annually, ideally with computed tomography

14

Due to the low incidence of SFTs, standardized surveillance guidelines do not exist, so follow-up should be individualized based on tumor location and patient factors

1

.

The patient in this clinical case belonged to the most frequent age group for this rare pathology and was symptomatic due to the tumor's size (27 cm in its largest diameter and weighing over 4 kg) and persistent hypoglycemia despite treatment. The patient's tumor was located in the left hemithorax; hypoglycemia is most commonly associated with tumors in the right hemithorax. Her serum C-peptide and insulin levels were below normal limits, which is common in Doege–Potter syndrome. The tomographic findings were similar to those described in the literature. Despite the low yield, the diagnosis was made through an ultrasound-guided transthoracic core needle biopsy. The histopathological report of the biopsy, and later the pathology report of the surgical specimen, were consistent with what is described in the literature. These findings, along with the immunohistochemistry result, STAT6 positive, are conclusive for the diagnosis of this condition. After tumor removal, hypoglycemia resolved, and the episodes of disorientation and drowsiness did not recur, resolving Doege–Potter syndrome. Although no infiltration or high mitotic activity was observed, the tumor's large size and its association with pleural effusion warrant long-term follow-up, as some cases are associated with recurrence or malignant degeneration.