Introducción

Abdominal pain has consistently remained the most frequent main complaint in emergency departments, accounting for between 7.1% and 8.8% of emergency visits annually

1

. In a private facility in Lima, Peru, abdominal pain represents the second most common reason for emergency consultation, constituting up to 13% of all visits

2

. This symptom, often associated with gastrointestinal pathologies, can also indicate more severe and less common conditions, such as hereditary spherocytosis (HS), a hemolytic anemia that requires a meticulous differential diagnostic approach

3

.

Hereditary spherocytosis is a genetic disease that affects the red blood cell membrane, usually inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Affected individuals often present with anemia, jaundice, and splenomegaly. During stress situations, such as infections, even mild cases can worsen and lead to hemolytic crises

4

.

This report highlights a case of HS characterized by unusual abdominal pain, illustrating the importance of considering atypical diagnoses in emergency medicine. Abdominal pain is often mistakenly attributed to common causes without thorough analysis, which could reveal rarer but significant underlying pathologies. The objective is to examine a case of HS presenting as abdominal pain in the emergency department and to emphasize the need for a broader differential diagnosis. Additionally, it aims to raise awareness of the importance of considering and diagnosing rare conditions that can mimic more common ones in emergency situations.

A case is presented of a young male patient from a dengue-endemic area who was admitted to the emergency room with abdominal pain, jaundice, and splenomegaly. The combination of symptoms and geographical location initially suggested other diseases, but the final diagnosis was hemolytic crisis in HS. This case underscores the need for a detailed medical history and careful interpretation of laboratory tests and imaging studies to avoid misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatments.

Case Report

A 22-year-old male patient with a history of jaundice and dark urine since childhood, and gallstones diagnosed in 2021; the patient's mother also has a history of jaundice and dark urine, both without a diagnosis. The patient has no surgical history, denies drug use, exposure to toxic substances, or rodent bites.

The clinical picture is characterized by fever, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea seven days before admission to the emergency room; subsequently, he presented with diffuse moderate abdominal pain, mainly localized in the right upper quadrant and epigastrium, colicky in nature; low back pain and dyspnea. On physical examination, jaundiced and pale skin was observed, with abdominal pain predominantly in the right hypochondrium, negative Murphy's sign, and no peritoneal signs. The laboratory workup showed leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, alanine aminotransferase 874 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 1785 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 485 U/L, total bilirubin 4.15 mg/dl, direct bilirubin 1.77 mg/dl, lactate dehydrogenase 2647 U/L. The abdominal ultrasound described hepatosplenomegaly, a distended gallbladder with thickened and edematous walls of up to 6 mm, with a stone of approximately 25 mm inside and perivesicular fluid, a portal vein of 8 mm, and a common bile duct of 6.5 mm. The test for dengue was negative: NS1 antigen non-reactive, IgM non-reactive, IgG non-reactive; direct Coombs test negative, no parasitic forms observed in the thick blood smear, haptoglobin 10 mg/dl, reticulocytes 5.9%. Finally, the peripheral blood smear showed 40% spherocytes, and the IgM for dengue by ELISA method was positive.

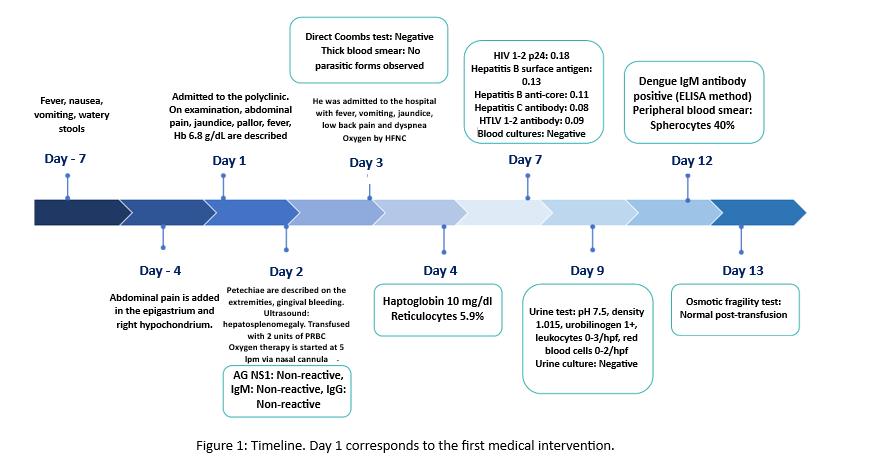

A timeline is presented (Figure 1), showing the main symptoms and laboratory results performed as part of the differential diagnosis.

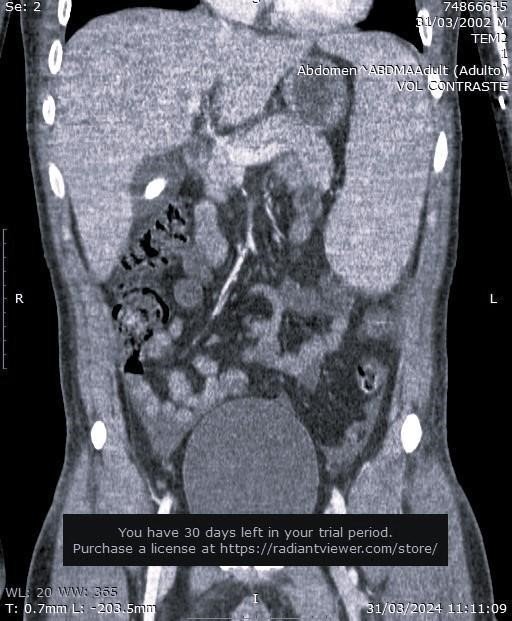

Based on the patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings (Table 1), this case corresponds to a patient with hereditary spherocytosis who presented with a hemolytic crisis; the trigger was a viral dengue infection. A coronal section contrast-enhanced CT image is attached (Figure 2). The patient's evolution was favorable; he was treated with fluids (0.9% NaCl), analgesics, folic acid, transfusion support, and empirical antibiotic coverage, which was discontinued on the fifth day.

Discussion

This patient presented with clinical signs of an underlying hemolytic disease characterized by anemia, jaundice, splenomegaly, and cholelithiasis, a finding frequently observed in cases of chronic hemolysis. A review of the literature suggests that these symptoms indicate hereditary spherocytosis, a condition where red blood cell protein abnormalities are observed. Laboratory findings, including variable hemoglobin (Hb) levels, an increase in reticulocyte count and spherocytes, and elevated total serum bilirubin, reinforce this diagnosis. These symptoms and laboratory findings are consistent with those reported in the literature, where most patients exhibit an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and clinical manifestations similar to other family members

5

.

The patient in this study meets the diagnostic criteria for hereditary spherocytosis, strongly suggesting this diagnosis in his case. During the differential diagnosis process, it is crucial to rule out other extravascular hemolytic anemias. A characteristic feature of hereditary spherocytosis is the observation of increased mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), red cell distribution width (RDW), and reticulocyte count, with a mean corpuscular volume (MCV) that may be normal or reduced, sometimes accompanied by varying degrees of anemia. An important aspect to consider is the MCHC/MCV ratio, which, if greater than 0.36, increases the likelihood of hereditary spherocytosis. Biochemical analyses may show an increase in serum bilirubin, predominantly unconjugated, and in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), along with a decrease in haptoglobin levels. Compared to other hemoglobinopathies, microcytic hemolytic anemia characterized by the presence of sickle cells, target cells, and Heinz bodies is commonly found. On the other hand, autoimmune hemolytic anemia is distinguished by a positive direct Coombs test; in type II dyserythropoietic anemia, a decrease in reticulocyte count is observed; in pyropoikilocytosis, a marked decrease in MCV is typical, while in congenital elliptocytosis, MCV, MCHC, and LDH values remain normal

6

.

It should be noted that specific confirmatory tests, such as the osmotic fragility test, are not feasible in most emergency centers, especially in patients who have received transfusions within the first 48 hours, as these tests may yield false-negative results. Therefore, basing the diagnosis on the clinical suspicion of a hemolytic disease, supported by findings in the complete blood count, becomes a crucial and highly useful tool.

The diagnosis of jaundice and acute abdominal pain represents a significant challenge for emergency physicians, particularly when the patient's condition suggests systemic involvement or the coexistence of other underlying pathologies. In regions of our country, where dengue prevalence is high, and considering the increase in outbreaks reported from 2023 to 2024, initial symptoms such as fever, abdominal pain, anemia, and thrombocytopenia were attributed to this disease. However, the negativity of IgM antibodies for dengue, combined with leukocytosis and a history of jaundice since childhood, prompted a reassessment and deeper analysis of the underlying causes of the clinical presentation

11

.

The appearance of anemia and abdominal pain in a patient diagnosed with dengue commonly suggests the possibility of a severe form of the disease. However, in individuals with hereditary spherocytosis, infections such as dengue can trigger a hemolytic crisis and present with similar symptoms, such as pallor, jaundice, lower back pain, abdominal pain, and fever. The concurrent appearance of these symptoms makes it essential to carefully differentiate between signs of severe dengue and the effects of a hemolytic crisis

12

,

13

. In dengue, high levels of transaminases, severe thrombocytopenia, atypical lymphocytes, and polyserositis indicate the severity of the clinical picture. Additionally, a high white blood cell count, above 6000 cells/mm³, has been linked to the progression to dengue shock syndrome in adults. This situation is particularly concerning in patients with hemolysis, in whom these levels may be frequent and can confuse the diagnosis

14

.

In dengue, combined NS1 and IgM antibody tests are useful for providing an early diagnosis, usually within the first seven days of illness. However, if these test results are negative and clinical suspicion of dengue persists, based on the local epidemiology and the patient's symptoms, it is recommended to obtain a second sample during the convalescent phase to perform the IgM test. This method ensures that antibodies can be reliably detected, which can occur up to approximately 12 weeks after infection

12

,

15

,

16

. In the presented case, the IgM test was positive on day 12 of the disease, confirming the dengue infection.

Additionally, this patient tested positive for RPR and antibodies against Treponema pallidum, which, in an individual never treated for syphilis, indicates the need to initiate treatment with benzathine penicillin. While cases of syphilitic hepatitis in the secondary stage have been reported in 0.2% to 3% of patients with syphilis

17

,

18

, caracterizado por un patrón colestásico con elevación de las enzimas hepáticas con evidencia treponémica serológica

19

,

20

, characterized by a cholestatic pattern with elevated liver enzymes and serological evidence of treponemal infection (19,20), the positive IgM test for dengue, combined with the presence of severe anemia, thrombocytopenia, and markedly elevated transaminases in a patient without skin rashes, steers the diagnosis away from syphilis.

The positive findings of IgG antibodies for cytomegalovirus, herpes 1 and 2, and Toxoplasma gondii also suggest prior exposure to these pathogens, adding complexity to the diagnosis and management of the case.

The treatment administered consisted of intravenous hydration with 0.9% saline solution, administration of paracetamol and morphine for pain control, folic acid, and transfusion support; additionally, oxygen therapy via high-flow cannula was provided. Elective cholecystectomy and an update of the vaccination schedule were considered, and the patient was prepared for a possible splenectomy. The multidisciplinary management strategy adopted in the emergency room, with the collaboration of gastroenterology, hematology, and surgery teams, was crucial in achieving a favorable outcome and avoiding the need for urgent surgical interventions.

This case stands out as one of the few reports of spherocytosis in adults complicated by hemolysis triggered by a prevalent viral infection such as dengue. Lam J

21

documented this case in 2019, where a patient with hereditary spherocytosis developed secondary hemolysis due to dengue. A similar case was reported by Tateno Y et al.

22

, in a patient with pyelonephritis and jaundice who had not previously been diagnosed with hereditary spherocytosis.

In a patient with a history of cholelithiasis who presents to the emergency room with abdominal pain, it is very important to perform a detailed medical history and a meticulous clinical interpretation of laboratory tests, adapted to local epidemiology, especially in contexts where inadequate follow-up and limited resources may contribute to delayed diagnoses. The presence of jaundice from an early age, the finding of splenomegaly on ultrasound, and changes in the blood count should prompt consideration of causes of abdominal pain originating outside the digestive system. In tropical areas, where diseases like dengue are prevalent, it is crucial to consider these factors as potential triggers for a hemolytic crisis.

Figure 1

Timeline. Day 1 corresponds to the first medical intervention.

Table 1. Laboratory Results

|

COMPLETE BLOOD COUNT

|

VIRAL PANEL

|

|

Day 1 |

Day 3 |

Day 4 |

Dengue |

Day 2 |

AG NS1: Non-reactive, IgM: Non-reactive, IgG: Non-reactive (immunochromatography method)

|

| Leukocytes |

K/ul |

18200 |

14140 |

10160 |

|

Day 2 |

Dengue IgM antibody POSITIVE (ELISA method)

|

| Neutrophils |

K/ul |

8540 |

6500 |

5880 |

HIV |

Day 7 |

HIV 1-2 p24: 0.18

|

| Lymphocytes |

K/ul |

9420 |

3930 |

1016 |

HEP B |

Day 7 |

Hepatitis B surface antigen 0.13, Hepatitis B anti-core antibody 0.11

|

| Hemoglobin |

g/dL |

6.8 |

8.3 |

6.8 |

HEP C |

Day 7 |

Hepatitis C antibody 0.08

|

| Hematocrit |

% |

19.9 |

23.4 |

19.2 |

HTLV |

Day 7 |

HTLV 1-2 antibody 0.11

|

| MCV |

fL |

98.2 |

91.4 |

91 |

CMV |

Day 12 |

Cytomegalovirus IgG antibody 216.8 UA/mL reactive, Cytomegalovirus IgM antibody 0.12 non-reactive

|

| MCHC |

g/dL |

34.2 |

35.5 |

35.4 |

HERPES 1 |

Day 12 |

Herpes 1 IgM 1.782 negative, Herpes 1 IgG 34.57 positive

|

| MCHC/MCV |

|

0.35 |

0.39 |

0.39 |

HERPES 2 |

Day 12 |

Herpes 2 IgM 1.87 negative, Herpes 2 IgG 16.58 positive

|

| RDW |

% |

19.9 |

20.4 |

|

TOXOPLASMA |

Day 12 |

Toxoplasma gondii IgG antibody 12.9 reactive, Toxoplasma gondii IgM antibody 0.08 non-reactive

|

| Platelets |

K/ul |

52000 |

55000 |

49000 |

|

| Reticulocytes |

% |

|

|

5.9% |

|

| Haptoglobin |

mg/dL |

|

|

10 |

|

| Peripheral blood smear |

Spherocytes 40% |

|

| Osmotic fragility test |

Normal |

|

|

| HEPATIC AND BIOCHEMICAL PROFILE |

BACTERIAL PANEL |

|

Day 1 |

Day 3 |

|

SYPHILIS |

Day 6 |

Anti-Treponema pallidum antibody (chemiluminescence test) 1.81, RPR reactive

|

| AST |

U/L |

1785 |

630 |

BLOOD CULTURE |

Day 7 |

Negative |

| ALT |

U/L |

874 |

485 |

URINE CULTURE |

Day 9 |

Negative |

| TB/DB |

mg/dL |

|

3.89/2.1 |

URINALYSIS |

Day 9 |

pH 7.5, density 1.015, urobilinogen 1+, leukocytes 0-3/hpf, red blood cells 0-2/hpf

|

| Alkaline Phosphatase |

U/L |

|

479 |

|

| Glucose |

mg/dL |

86 |

|

PARASITOLOGY |

| Urea |

mg/dL |

33.8 |

|

THICK BLOOD SMEAR |

Day 3 |

No parasitic forms observed |

| Creatinine |

mg/dL |

0.64 |

|

|

| Sodium |

mmol/L |

140 |

|

IMMUNOLOGICAL PANEL |

| Potassium |

mmol/L |

4.27 |

|

DIRECT COOMB |

Day 2 |

Negative |

| Procalcitonin |

mmol/L |

|

0.91 |

DIRECT COOMB |

Day 3 |

Positive 1+ (after starting antibiotics) |

| LDH |

U/L |

|

2647 |

Direct human antiglobulin test (monospecific) |

Monospecific anti IGG 1+ |

| Lipase |

U/L |

|

108 |

|

Monospecific anti IGA - |

| Amylase |

U/L |

|

78 |

Monospecific anti IGM - |

|

Monospecific anti C3C - |

| COAGULATION PROFILE |

Monospecific anti C3D - |

| Fibrinogen |

mg/dL |

|

305.74 |

|

| aPTT |

sec |

|

12.35 |

| PT |

sec |

|

42.71 |

| TT |

sec |

|

41.05 |

* MCV: Mean Corpuscular Volume, MCH: Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin, MCHC: Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration, RDW: Red Cell Distribution Width, AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase (TGO), ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase (TGP), LDH: Lactate Dehydrogenase, TB: Total Bilirubin, DB: Direct Bilirubin, IB: Indirect Bilirubin, ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase, PT: Prothrombin Time, aPTT: Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time, TT: Thrombin Time, CMV: Cytomegalovirus, RPR: Rapid Plasma Reagin.

Conclusion

Abdominal pain can be indicative of an extra-gastrointestinal condition. In this context, it is crucial to recognize that transient anemia or jaundice may sometimes be the only initial signs of previously undiagnosed hereditary spherocytosis. The presence of leukocytosis, which is not characteristic of dengue, should prompt consideration of other diseases in patients with a history of cholelithiasis and jaundice since childhood. Hereditary spherocytosis is a risk factor for cholelithiasis, and hemolysis exacerbated by another underlying pathology, such as dengue, can produce an atypical presentation of abdominal pain in patients presenting to the emergency room, especially if they reside in endemic areas. Conducting complementary studies with this approach in mind is vital to properly guide the diagnosis and management of the patient.