INTRODUCTION

Cesarean section is the most commonly performed obstetric surgery worldwide

1–3

, and its incidence has risen significantly in recent years

1, 3

. Although generally considered a low-risk procedure, it may impact the health and well-being of both the mother and newborn

4

.

Spinal anesthesia is the most widely used technique for cesarean section because of its rapid onset and high efficacy

5, 6

. However, one of its most frequent complications is maternal hypotension, which affects up to 80% of patients undergoing this type of anesthesia

7, 8

. This condition is caused by peripheral vasodilation secondary to sympathetic blockade, leading to a drop in blood pressure

1

that may compromise maternal and fetal well-being. Therefore, timely and effective management is essential

4, 9

.

Among the strategies to prevent maternal hypotension, the prophylactic and routine use of vasopressors has proven to be effective

10

. Among the vasopressors used, norepinephrine has shown high effectiveness in preventing maternal hypotension. Recent studies have found that doses greater than 0.05 μg/kg/min significantly reduce the incidence of hypotension without compromising neonatal safety, with an effective dose for 90% of patients (ED90) estimated at 0.100 μg/kg/min for singleton pregnancies and 0.098 μg/kg/min for twin pregnancies

11

. Additionally, in low-resource settings, continuous infusion within a range of 0.028 to 0.057 μg/kg/min has maintained stable blood pressure in 96.4% of patients without maternal or neonatal adverse effects

6

.

Globally, the most commonly used vasopressors to prevent and treat this complication are phenylephrine and norepinephrine

1, 10

. In Latin America, particularly in countries such as Peru, etilefrine is a widely used option; however, it lacks sufficient scientific support, leading to its discontinuation in several countries

12, 13

. Recent scientific evidence from developed countries suggests that norepinephrine provides better maternal and neonatal outcomes

1, 4, 14, 15

.

Therefore, it is essential to compare etilefrine and norepinephrine in our population

1, 15

. The lack of specific studies on the stability and safety of etilefrine in local populations, such as the Peruvian one, prevents us from determining whether its performance is inferior or comparable to that observed in other international settings

1, 4, 13

. In this regard, it is crucial to develop rigorous research to support informed decision-making and adapt maternal hypotension management guidelines to different socioeconomic and geographic realities, with the goal of maximizing maternal–fetal safety. The aim of this study was to determine and compare the effectiveness of etilefrine versus norepinephrine (in bolus or continuous infusion) in preventing maternal hypotension during cesarean section under spinal anesthesia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and area. A prospective analytical observational cohort study was conducted at the Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal (INMP) in Lima, Peru, between 2022 and 2024. The INMP is a national referral center for maternal and perinatal health that handles a high volume of deliveries and cesarean sections, offering an optimal setting to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of different maternal hypotension prevention strategies.

Population and sample. The total population comprised approximately 2,119 pregnant women scheduled for cesarean section under spinal anesthesia from 2022 to 2024. From this population, a sample of 300 women classified as categories 3 and 4 according to Lucas et al.

16

was selected and divided into three groups of 100. The statistical power was calculated based on expected hypotension incidences of 11.7% and 1.7% according to previously reported treatments

17

, with a 95% confidence level, resulting in a power of 81.2% using the normal approximation. Inclusion criteria were: maternal age between 18 and 40 years, gestational age between 37 and 41 weeks, body mass index (BMI) of 20 to 38 kg/m², and Pfannenstiel surgical technique with uterine exteriorization. Exclusion criteria included contraindications to regional anesthesia, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, chronic maternal diseases, multiple gestations, fetal congenital malformations, or known allergy to the study medications.

Variables and instruments. Participants were assigned to one of three groups of 100 patients each, based on the vasopressor administered by the attending anesthesiologist: etilefrine bolus (EB group), norepinephrine bolus (NB group), and norepinephrine infusion (NCI group). The independent variable was the type of vasopressor used in each group. The primary clinical outcome was the incidence of hypotension, assessed by the number and percentage of episodes recorded in each group. To evaluate neonatal safety, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes were compared between groups. Additionally, demographic and anthropometric variables (maternal age, BMI, gestational age), anesthesia-related variables (vasopressor administration time), and maternal hemodynamic variables (systolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, and heart rate) were recorded. Data collection was performed using medical records and a structured data collection form.

Procedures. During routine care of pregnant women undergoing cesarean section under spinal anesthesia, the institutional protocol for hemodynamic monitoring and management was followed. Anesthesia was administered in the sitting position using a 27-gauge Whitacre needle at the L3–L4 interspace, confirming correct positioning via cerebrospinal fluid return. The anesthetic mixture included 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine (10 mg), fentanyl (20 μg), and morphine (100 μg). Simultaneously, the assigned vasopressor was administered (norepinephrine via continuous infusion or 8 μg boluses, or etilefrine in 2 mg boluses). Crystalloid fluids were given at 20 mL/kg, with continuous monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate, electrocardiogram, and oxygen saturation. In cases of maternal hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg or a >20% drop from baseline), rescue doses of the assigned vasopressor were administered (2 mg of etilefrine in the EB group or 6 μg of norepinephrine in the NB and NCI groups). The number of rescue boluses administered during each hypotensive episode was recorded.

Medical records were identified and selected consecutively based on daily access availability in the operating room schedule, as each anesthetic management group became available, until reaching 100 medical records per group. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were reviewed to ensure eligibility.

Statistical analysis. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were calculated for continuous variables. Means between the three groups were compared using ANOVA, and Student’s t-test was used for pairwise group comparisons. Both the total number of hypotension episodes and the proportion of patients with at least one episode were analyzed using Student’s t-test and the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATET) for each vasopressor group comparison. To adjust for potential baseline differences between groups, Propensity Score Matching (PSM) was applied for the final indicator. This method confirmed both the percentage of bias reduction for each covariate (with covariates including Apgar score at 1 minute, maternal age, height, weight, and gestational age) and the balance in treatment assignment probability distribution. The former ensures that there are no systematic differences in covariates that could confound the treatment effect, while the latter confirms that the probabilities of belonging to each group are sufficiently random to be considered valid and comparable across groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all statistical analyses.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal under report number 049/2024-CIEI/INMP. All participants signed an informed consent form prior to inclusion, in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and local regulations for observational clinical studies.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the maternal age, weight, and gestational age of the women undergoing cesarean section, distributed across the three treatment groups. No significant differences were observed in age (p=0.360) or BMI (p=0.540) among the groups. However, gestational age was significantly lower in the group treated with norepinephrine infusion (p=0.013) (37.8 weeks), although the difference was not clinically relevant.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of maternal age, BMI, and gestational age by vasopressor group among cesarean patients at INMP

| Variable |

Bolus Etilefrine |

Bolus Norepinephrine |

Continuous Norepinephrine |

p-value |

| (N=100) |

(N=100) |

(N=100) |

| Age (years) |

30.2±6.4 |

31.4±5.9 |

30.9±5.6 |

0.360 |

| BMI (kg/m²) |

30.5±4.0 |

29.9±3.0 |

30.2±3.4 |

0.540 |

| GA (weeks) |

38.3±1 |

38.2±0 |

37.8±1 |

0.013 |

BMI: Body Mass Index; GA: Gestational Age.

Table 2 compares the vasopressors based on administration time and Apgar scores. The mean administration time was 19.49 minutes in the EB group and 18.18 minutes in the NB group, with a significant difference of 1.31 minutes (p=0.042). Regarding the Apgar test, no significant differences were found in the mean scores at 1 minute (–0.13; p=0.870) or at 5 minutes (–0.09; p=0.710) between the groups.

Table 2. Differences in mean administration time and APGAR scores by vasopressor group used.

| Comparison |

BE – BN Mean difference (p) |

BE – CNI Mean difference (p) |

BN – CNI Mean difference (p) |

| Administration time (minutes) |

19.49 – 18.18 |

19.49 – 18.66 |

18.18 – 18.66 |

| 1.31 (0.042) |

0.83 (0.365) |

0.48 (0.540) |

| APGAR at 1 minute |

7.87 – 8.00 |

7.87 – 8.02 |

8.00 – 8.02 |

| -0.13 (0.870) |

-0.15 (0.090) |

-0.02 (0.620) |

| APGAR at 5 minutes |

8.91 – 9.00 |

8.91 – 9.00 |

9.00 – 9.00 |

| -0.09 (0.710) |

-0.09 (0.210) |

0.00 (not calculated) |

BE: Bolus Etilefrine (2 mg). BN: Bolus Norepinephrine (8 µg). CNI: Continuous Norepinephrine Infusion (0.05 µg/kg/min).

To ensure valid comparisons and reduce initial differences between groups (for each group pair), the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) method was applied. Figure 1 shows a significant improvement in covariate balance after matching, with a notable reduction in the percentage of standardized bias in variables such as Apgar score, maternal age, weight, height, and gestational age.

Figure 1

Standardized bias percentage balance according to covariates before and after matching. A) NB vs. NEI. B) EB vs. NEI. C) EB vs. NB.

EB: Ephedrine bolus (2 mg). NB: Norepinephrine bolus (8 µg). NEI: Continuous norepinephrine infusion (0.05 µg/kg/min).

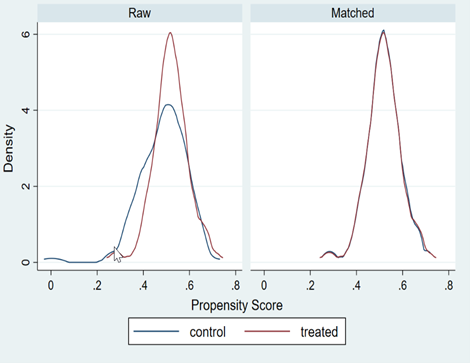

Figure 2 confirms the alignment of distributions between treated and untreated groups, reinforcing the validity of the analysis. Initially, each pair of histograms (unmatched) showed some disparities, but after matching, the distributions (matched) almost completely overlapped.

Figure 2

Distribution of the propensity score before and after propensity score weighting, evaluating the common support among treated patients. A) NB vs. NEI. B) EB vs. NEI. C) EB vs. NB.

EB: Ephedrine bolus (2 mg). NB: Norepinephrine bolus (8 µg). NEI: Continuous norepinephrine infusion (0.05 µg/kg/min).

Figure 3 shows the trend in baseline systolic blood pressure across the study groups. The average baseline values were 114.31 ± 16.31 mmHg in the EB group, 112.37 ± 12.79 mmHg in the NB group, and 113.93 ± 12.25 mmHg in the NCI group. During the first 20 minutes, the NCI group maintained a stable systolic blood pressure, unlike the NB and EB groups, which showed fluctuations. At minute 3, values were 100 ± 15.21 mmHg and 103 ± 16.82 mmHg, respectively, while at minute 7.5, a value of 98 ± 13.73 mmHg was recorded

Figure 3

Trend of maternal hemodynamic variable means according to the type of vasopressor used during the perinatal period.

A: Maternal systolic blood pressure (from vasopressor administration to delivery);

B: Maternal mean arterial pressure (from local anesthetic administration to delivery);

C: Maternal heart rate (from bolus/infusion of vasopressor to delivery).

Figure A (maternal systolic blood pressure) showed baseline mean values of 114.31±16.31 mmHg (EB), 112.37±12.79 mmHg (NB), and 113.93±12.25 mmHg (NCI), with stability observed in the NCI group during the first 20 minutes, while EB and NB fluctuated (e.g., 100±15.21 vs. 103±16.82 mmHg at 3 minutes). Figure B (maternal mean arterial pressure) recorded baseline averages of 83.5±11.25 mmHg (EB), 79.0±10.51 mmHg (NB), and 81.0±10.95 mmHg (NCI), highlighting consistency in the NCI group after anesthesia, in contrast to transient drops in EB/NB (69±12.08 mmHg at 3 minutes). In Figure C (maternal heart rate), the EB group presented a sustained increase (>80 bpm; baseline: 82.8±11.28 bpm), contrasting with the stability observed in NCI (72±10.26 bpm at 3 minutes) and moderate oscillations in NB (baseline: 79.06±10.11 bpm). Collectively, NCI demonstrated greater hemodynamic stability, while EB/NB exhibited significant variations (p<0.05 in intergroup comparisons), highlighting pharmacodynamic differences between vasopressors.

Table 3. Comparison of hypotension episodes by vasopressor group in patients undergoing cesarean section under spinal anesthesia

| Comparison* |

Mean difference (p-value) |

Mean difference (%) (p-value) |

ATET of number of episodes (p-value) |

ATET of percentage of episodes (p-value) |

| BE vs. BN |

-0.02 (0.940) |

6% (0.376) |

0.02 (0.949) |

8.08% (0.341) |

| BE vs. CNI |

-1.03 (<0.001) |

-39% (<0.001) |

-1.36 (0.003) |

-35% (<0.001) |

| BN vs. CNI |

-1.01 (<0.001) |

-45% (<0.001) |

-1.24 (<0.001) |

-47% (<0.001) |

* The mean and percentage difference values are interpreted as the result of subtracting the value of the group on the right from that of the group on the left.

ATET: Average Treatment Effect on the Treated.

BE: Bolus Etilefrine (2 mg).

BN: Bolus Norepinephrine (8 µg).

CNI: Continuous Norepinephrine Infusion (0.05 µg/kg/min).

DISCUSSION

Etilefrine and norepinephrine are two vasopressors widely used in clinical practice for the prevention and management of spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension during cesarean section

18, 19

. Although etilefrine is commonly used in Latin America, it lacks approval from regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), raising concerns about its efficacy and safety. In contrast, norepinephrine has been widely adopted due to its proven effectiveness in maintaining hemodynamic stability. This study, which included a larger sample than previous investigations in the region, aims to serve as a foundation for future research in various high-risk obstetric subpopulations, such as patients with obesity or hypertensive disorders.

Our results showed that continuous infusion of norepinephrine at a dose of 0.05 μg/kg/min provided greater hemodynamic stability compared to bolus administration of norepinephrine or etilefrine. The incidence of hypotensive episodes was 35% lower in the group receiving norepinephrine infusion compared to the etilefrine group, highlighting the superiority of this strategy in preventing maternal hypotension. This finding is consistent with previous studies, such as that by Wei C. et al., which demonstrated that doses above 0.05 μg/kg/min of norepinephrine significantly reduce the incidence of hypotension in patients undergoing cesarean section under spinal anesthesia

20

. Additionally, in our study, both systolic and diastolic blood pressure remained more stable in the norepinephrine infusion group, whereas more pronounced hemodynamic fluctuations were observed in the etilefrine group, further supporting the preference for continuous infusion.

A study by Alegre P. et al. compared the efficacy of norepinephrine and etilefrine and reported that norepinephrine infusion better maintained maternal hemodynamic parameters than bolus administration of etilefrine (2 mg) or norepinephrine (5 μg)

21

. Our study, which used a norepinephrine infusion dose of 0.05 μg/kg/min adjusted to ideal body weight by height, showed a lower incidence of maternal hypotension and greater hemodynamic stability compared to the other groups. Regarding dosage, Wei C. et al. conducted a double-blind trial to determine the optimal norepinephrine infusion dose and concluded that doses between 0.05 and 0.075 μg/kg/min significantly reduce hypotension incidence

20

. These results are in line with our study, in which norepinephrine infusion demonstrated better hemodynamic outcomes (systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure) than etilefrine or bolus norepinephrine.

Brebion M. et al. reported that norepinephrine is as effective as phenylephrine in preventing maternal hypotension but with the added benefit of better maintaining cardiac output and maternal heart rate

22

. In our study, maternal heart rate remained more stable in the norepinephrine infusion group compared to the etilefrine bolus group, where a significant increase was observed. This increase can be attributed to the beta-adrenergic action of etilefrine, which may pose a risk in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions. These findings align with those of Albisua-Aguilar et al., who reported that norepinephrine infusion significantly reduced the risk of maternal hypotension by 71% compared to bolus ephedrine, as well as decreased the incidence of nausea and vomiting. They also found that norepinephrine allowed better blood pressure control without affecting heart rate, suggesting it is a safer option for patients with higher cardiovascular risk

23

. In contrast, norepinephrine infusion not only maintained more stable blood pressure but also avoided the heart rate peaks associated with etilefrine, making it a safer alternative for patients at cardiovascular risk.

Regarding neonatal outcomes, specifically Apgar scores, no significant differences were found between the groups treated with continuous norepinephrine infusion, bolus norepinephrine, and bolus etilefrine. This suggests that, from a neonatal standpoint, these vasopressors are safe when properly administered, as Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes remained within normal ranges across all groups. These findings are consistent with those of Caravaca J.

24

, who also found no significant differences in Apgar scores when comparing ephedrine and norepinephrine during cesarean section under subarachnoid block. Similarly, previous reports have indicated that norepinephrine and phenylephrine do not negatively affect neonatal outcomes in terms of Apgar scores or fetal cardiac output

25, 26, 27

, supporting the use of norepinephrine as a safe alternative to ephedrine for hypotension prophylaxis during cesarean section without differences in neonatal outcomes

28

. However, this comparison should be interpreted with caution, as it was not a primary objective of the study and was not adjusted using PSM, implying the possibility of uncontrolled baseline differences. Future research could explore additional parameters such as arterial blood gas analysis for a more comprehensive assessment of neonatal well-being, although the available findings may support the safety of norepinephrine infusion in this clinical context.

The use of propensity score weighting in our analysis was essential for ensuring robust comparisons and minimizing bias. This adjustment reaffirmed the superiority of norepinephrine infusion in preventing maternal hypotension, even after controlling for covariates. Previous studies, such as that by Boyda H. et al., have also emphasized the superiority of norepinephrine over other vasopressors in terms of maintaining cardiac output and avoiding significant blood pressure fluctuations

25

. The application of this method strengthens the validity of our findings and provides a more accurate comparison among the studied vasopressors.

Additionally, our findings align with a recent systematic review and meta-analysis showing that prophylactic norepinephrine infusion significantly reduces the incidence of hypotension and severe hypotension following spinal anesthesia for cesarean section, while also improving maternal hemodynamic stability

26

. The reduction in hypotension episodes in our study was similar to that reported in the meta-analysis, reinforcing the strength of our results. However, one aspect to consider is the higher incidence of reactive hypertension associated with norepinephrine, a side effect previously documented as well

22

. Despite this, the risk–benefit balance still favors its use in continuous infusion due to its ability to minimize abrupt hemodynamic fluctuations.

From a physiological perspective, the beneficial effects of norepinephrine may be attributed to its ability to effectively restore mean arterial pressure without compromising microcirculatory perfusion, as shown in previous prospective studies

27

. In our study, a steady trend in mean arterial pressure was observed in the norepinephrine infusion group, while the bolus norepinephrine and etilefrine groups experienced oscillations. This finding supports the hypothesis that infusion administration enables more stable maternal hemodynamic regulation. Moreover, norepinephrine infusion has been reported to reduce the need for additional vasopressor doses, which is consistent with our results showing a lower incidence of hypotension without the need for frequent dose adjustments

28

.

Finally, the global increase in cesarean section rates, projected to reach 28.5% by 2030, underscores the importance of optimizing safe and effective anesthetic strategies to reduce the risk of complications

3

. In this context, the growing use of norepinephrine as the vasopressor of choice could contribute to improving maternal hemodynamic stability in cesarean sections under spinal anesthesia, and thus aligns with the need for evidence-based strategies to reduce risks in this increasingly common procedure. In terms of dosing, our findings highlight that norepinephrine infusion at 0.05 μg/kg/min was more effective in maintaining hemodynamic stability compared to the standard 2 mg bolus dose of etilefrine and 8 μg bolus of norepinephrine. This dosage is consistent with previous studies recommending doses above 0.05 μg/kg/min to maximize hemodynamic efficacy and reduce the incidence of hypotension

31, 32

.

One limitation of the study is the potential for selection bias, as the included patients may not represent the entire obstetric population, which could limit the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, the limited number of previous studies directly comparing etilefrine and norepinephrine poses challenges for the clinical interpretation of our findings. Nonetheless, conducting the study in a level III-2 referral institution with a diverse patient population helps to mitigate this limitation.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study indicate that continuous infusion of norepinephrine is more effective in preventing maternal hypotension during cesarean section under spinal anesthesia compared to bolus etilefrine and bolus norepinephrine. An additional finding was that systolic and mean arterial pressure, as well as heart rate, remained more stable under the continuous infusion scheme. Although no significant differences were observed in Apgar scores, this result should be interpreted cautiously, as it was not a primary endpoint of the study. Nonetheless, the data support the safety and efficacy of norepinephrine infusion for optimizing maternal hemodynamic stability without demonstrating adverse effects on neonatal outcomes.